The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

David Cameron pays respect but over-plays his hand in India

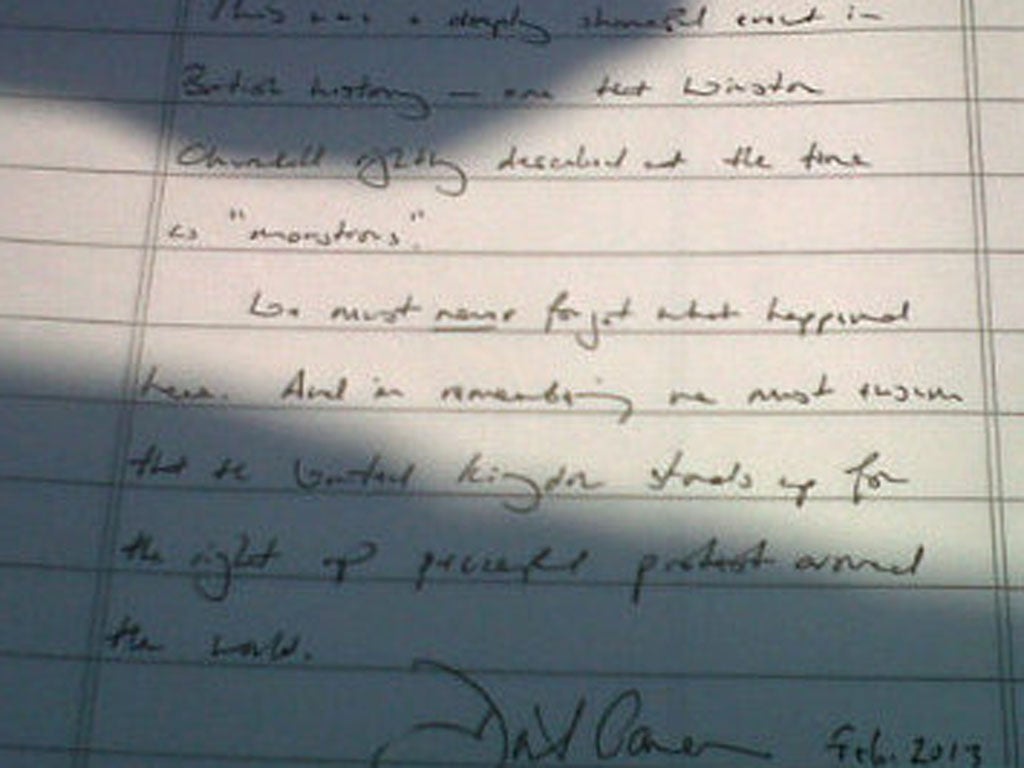

David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister, has ended his rather over-done public relations blitz in India with a sombre and respectful visit to the Jallianwala Bagh site of the 1919 Amritsar massacre, one of the worst atrocities of British rule, which he described as a “deeply shameful event in British history”.

He was the first British prime minister to go there and he also visited the nearby Golden Temple, the Sikh faith’s most sacred shrine, with an eye (as UK correspondents accompanying him noted) on the sizeable Sikh vote in the UK.

Always just a bit too keen and eager, Cameron swept into Mumbai on Monday morning with the news that he wanted to build “a very special partnership” with India, and repeated that yesterday at a joint press conference with his host, prime minister Manmohan Singh. He sounded rather like a senior prefect anxious to please the headmaster with an array of proposed achievements – instant visas for Indian businessmen, open doors for Indian students, and jointly developing a new-city corridor between Mumbai and Bangalore. He then sounded like an erring once-bullying husband anxious to rebuild family bonds when he said at the press conference that the “future of our two countries should be inextricably linked”.

The two countries aren’t of course inextricably linked, despite the colonial past, and Cameron won’t get very far pitching such lines at a government level.

Manmohan Singh was more interested at the press conference in pressing him for help investigating corruption allegations on a helicopter contract, while Ministry of External Affairs officials wanted him to stop ignoring India when he hosts Afghanistan-Pakistan talks, as he has been doing recently.

Cameron quickly promised co-operation on alleged corruption in an Italian owned (with UK involvement) Augusta Westland helicopter contract, and agreed a mechanism to keep India in the loop on his Af-Pak talks that are aimed, Indian sceptics believe, at unwisely courting the Taliban so as to try to stem Pakistani-born UK residents turning to terrorism.

The pitch goes down better with individual Indian businessmen and others, though there is still scepticism with people recognising that the main aim is to build on the strong role has in the UK with 1.5m Indian-born people living there and the Tata group being the UK’s biggest private sector employer.

Cameron made an impressive speech last night to an audience of a couple of thousand in the British High Commissioner’s home and garden in Delhi. Indian guests’ reactions ranged from “he was reminiscent of Bill Clinton” from a young lady academic economist, to “yes of course he’s over-egging it – he’s a pr man” from a more sceptical economics academic, and “he’s doing his job, he wants to create jobs in the UK so needs investment”, from a very seasoned journalist.

India is not going to build the “great relationship” (as Cameron rephrased it once or twice) with the UK and it is idle for him, in his eagerness to please, to over-pitch what can be achieved now that the role of world-wide colonial power and distance colony have been reversed into an offshore European island and rising one-day-to-be super power. Cameron is just one of the continuous flow of heads of foreign governments to India.

Francois Hollande of France was here on a much lower profile but effective visit until hours before Cameron flew in. Just before him came the king and the prime minister of Bhutan, a long-term friend and neighbour and more crucial to India’s interests than the UK or France. In the weeks before, there were presidents from two small but significant countries Mauritius (official India investment tax haven), Nepal (like Bhutan, a buffer state with China), and Vladimir Putin from Russia (India’s longest international partner).

So while there are many ways in which Britain and India can and will co-operate as old and future partners, it is silly to dress it up as something special, as Cameron also did in July 2010 when he arrived with a unprecedented posse of six cabinet ministers. This time he brought more than 100 businessmen which, he says, is the largest ever taken abroad by a UK prime minister.

India needs practical constructive partnership in developing the country and protecting its security, and it respects friends it can trust. Cameron’s best new offer was making visas available for Indian businessmen within 24 hours, instead of five days or longer as happens now, though that will be restricted to applications in Mumbai and Delhi. He also made news about students being welcome in the UK, though had nothing new to offer on that, despite many stories of students not managing to obtain visas.

Among other initiatives (listed in a joint statement). he talked about helping India develop new cities along a 1,000 km corridor between Mumbai and Bangalore, though the UK will not be offering the sort of multi-billion dollar aid provided by Japan for a Delhi-Mumbai corridor. It is primarily interested in obtaining contracts for British consultants, some of whom are already working on the Delhi-Mumbai project.

After all that, the best way for Cameron to get a partnership moving would be to generate interest about India in the UK, which is currently lacking. A British Council study last year found that, despite a shared history of 200 years, “Neither country has invested actively in building a contemporary relationship. India does not know contemporary Britain and Britain has little idea of how the new India is emerging. Stereotypes exist and remain damaging.” Officials also say that most British small and medium sized businessmen find India too daunting to try to access because of its size, unstable policy environment and corruption. That is where Cameron could best focus when he gets back to London.

* photo of David Cameron's note in the Jallianwala Bagh visitors' book by Andy Buncombe, The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks