No, it’s not time for Britain to be intensely relaxed over household debt

Evidence and theory suggest that when there’s a shock and confidence collapses households think less about their net worth and more about their gross nominal debt burden – specifically its relation to their expected future incomes.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Let us move from an economy built on debt to an economy that saves and invests for the future,” said the shadow Chancellor. But he should calm down. Household debt is no drama. Or so we’re increasingly told.

The idea that we should be worried about high leverage in the household sector has been criticised from all angles over recent weeks. Rupert Harrison, George Osborne’s former chief adviser, said it was a “myth”. Writers from The Economist and the Financial Times have taken issue with the idea too. As the author of an Independent front-page article published in December 2014, headlined “Revealed: Osborne’s debt time bomb”, I suppose I have a dog in this fight.

There seem to be three main arguments against the idea we should be concerned about household leverage. The first is that the official statistics belie the claim that the aggregate debt burden of UK households is rising and the recovery has been fuelled by borrowing.

Second, we’re told UK household debt is mainly mortgage debt and reflects high domestic house prices. For each of these liabilities there is an asset, so we must look at the overall balance sheets of households, which are healthy. Plus, with interest rates still on the floor, aggregate debt-servicing costs are comfortable.

Finally, we’re assured that as long as the supply of new homes remains severely restricted, high debt presents no serious financial threat because house prices are pretty unlikely to collapse. To illustrate this final point, it is pointed out that the banks failed in 2008 because of their dodgy overseas lending, not because of their dodgy UK mortgage books.

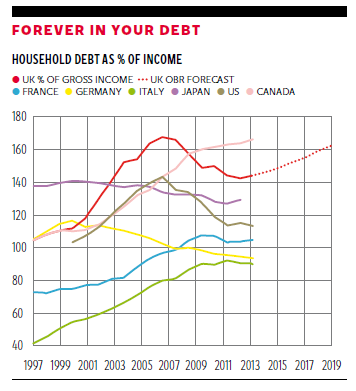

There are problems with all three arguments. Let’s take them in turn. Measured as a share of household incomes, it is true that household debt has not actually been growing. Since 2008, when the debt to income ratio peaked at 170 per cent, households have been deleveraging. Yet at 140 per cent of gross income, debt levels are still very high, both by historic and international standards.

In the G7 only Canada has a higher household leverage ratio today. There is potential fragility here if another economic shock were to hit, as the Bank of England itself admits. To point to the UK’s deleveraging in recent years as a reason for relief is akin to a mountaineer getting halfway down Everest in a vicious storm and saying “job done”.

Debt has not been rising as a share of income but the aggregate household savings ratio, excluding pension rights, has fallen from a peak of 6 per cent in 2010 to less than zero today. That change in household behaviour has certainly helped the economy recover. So not a recovery fuelled by debt, but a recovery fuelled by a lower savings ratio. Incidentally, there was no such savings collapse envisaged by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in 2010, reflecting how unbalanced the recovery has been relative to hopes six years ago.

Moreover, the OBR today predicts that the debt to income ratio is going to race back close to pre-crisis levels over the coming five years. Why? Because the Treasury’s official forecaster expects house prices to rise faster than incomes and for people to keep buying houses. The OBR is very far from being omniscient. But that is surely one of the more plausible assumptions from Robert Chote and his team, given the dismal evolution of the housing market in recent years and decades.

There is a necessary political observation to make here. Listen to the rhetoric from Mr Osborne and David Cameron about the evils of debt – that quote at the start of the article was made not by Labour’s John McDonnell but Mr Osborne in his February 2010 Mais lecture at the Cass Business School in London. And no he wasn't talking solely about government debt. His defenders must concede that if it’s a “myth” that private sector debt is a relevant economic concern today, it must also have been a myth in 2010.

Do high house prices reflect a deficient supply of new homes? To a large extent, yes. But remember the credit cycle too. As Lord (Adair) Turner, the former chair of the Financial Services Authority, argues in his new book Between Debt and the Devil, bank mortgage lending secured on housing collateral is inherently pro-cyclical. The more the housing stock rises in value, the more the collateral is worth and the more banks will be inclined to lend against it.

As Lord Turner puts it: “Lending against real estate generates self-reinforcing cycles of credit supply, credit demand and asset prices.” It is by no means clear that the Bank of England’s new suite of “macroprudential” tools will be sufficient to counteract that perilous tendency.

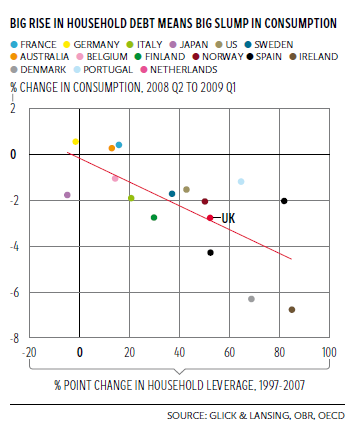

It’s true that in the global financial crisis UK house prices did not totally collapse, as they did in the US, Spain and Ireland – probably because we never had a comparable pre-crisis residential over-building boom. But Britain nevertheless went through the most severe economic recession since the 1930s. Evidence assembled by Reuven Glick and Kevin Lansing for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco shows that the countries with the biggest rises in household debt before the financial crisis also had the biggest declines in household consumption in its aftermath.

Evidence (from the Bank of England here) and theory (from Paul Krugman here and Mervyn King here) suggest that when there’s a shock and confidence collapses, households think less about their net worth and more about their gross nominal debt burden – specifically its relation to their expected future incomes. People with large nominal debts relative to their incomes cut their spending sharply to bring the ratio down. And there’s no countervailing spending increase from those whose are not in heavy debt, meaning the overall economy takes a hit.

That deleveraging impulse is also likely to be one of the reasons the recovery has been so weak by historic standards; large debt overhangs dissuaded people from spending, at least until the beginning of 2013 when the savings ratio lurched downwards.

It’s true that some claims by less statistically literate commentators about rising debt have run ahead of the evidence. Debt levels, properly measured, are not yet back to pre-crisis levels. And borrowing over the coming five years may not take off in the way that the OBR envisages. It’s unwise to assert that we are inevitably heading for another financial crash. Nor should we be distracted from the policy imperative of building many more houses and reforming the banks.

Yet the rather blasé blanket some are trying to throw over the issue of private debt is potentially dangerous. High household leverage - and the prospect of it rising even further - is indeed something to take seriously.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments