Nigel Farage as prime minister in 2029? Don’t be silly

The leader of Reform UK launched his manifesto for disaffected Tories today, writes John Rentoul. Do they really think he could be their saviour?

Reform UK doesn’t have a manifesto as such, it has a “contract”. Nigel Farage explained: “If I say to you ‘manifesto’, your immediate word association is ‘lie’.” And it doesn’t have policies as such, it has slogans, symbolic gestures and pub-bore cliches.

Which, to me, makes sense, because it is not a political party, rather it appears to be a private company for the promotion of the ego of its proprietor, Nigel Farage. And he is not running to be prime minister, as he admitted at the launch of “Our Contract With You” in Merthyr Tydfil today: “I’m not going to pretend we’re going to win.”

But he was going to pretend that he could win next time, and that his aim is to be prime minister in 2029. That has a fleetingly plausible ring to it, and sounds less like a snake-oil preacher predicting the Rapture, just as the two pages of “costings” at the end of the “Contract” document look like a ChatGPT version of something the Institute for Fiscal Studies might endorse.

Even before Farage launched the manifesto, one newspaper carried the headline, “Do Reform’s pledges on migrants, tax, crime and the NHS add up?” It was a rhetorical question. Of course they do not add up. That is not what they are for. Everyone knows that arithmetic is an establishment conspiracy to deny Farage and before him Liz Truss and Jeremy Corbyn their rightful places at the top of the tree.

Thus, Reform promises a humongous tax cut in the form of doubling the personal allowance, taking most of the median voter’s earnings out of income tax altogether, combined with big increases in public spending on the NHS, defence and schools. The gap to be made up by slashing other government spending and some other things that are all written down and definitely not made up.

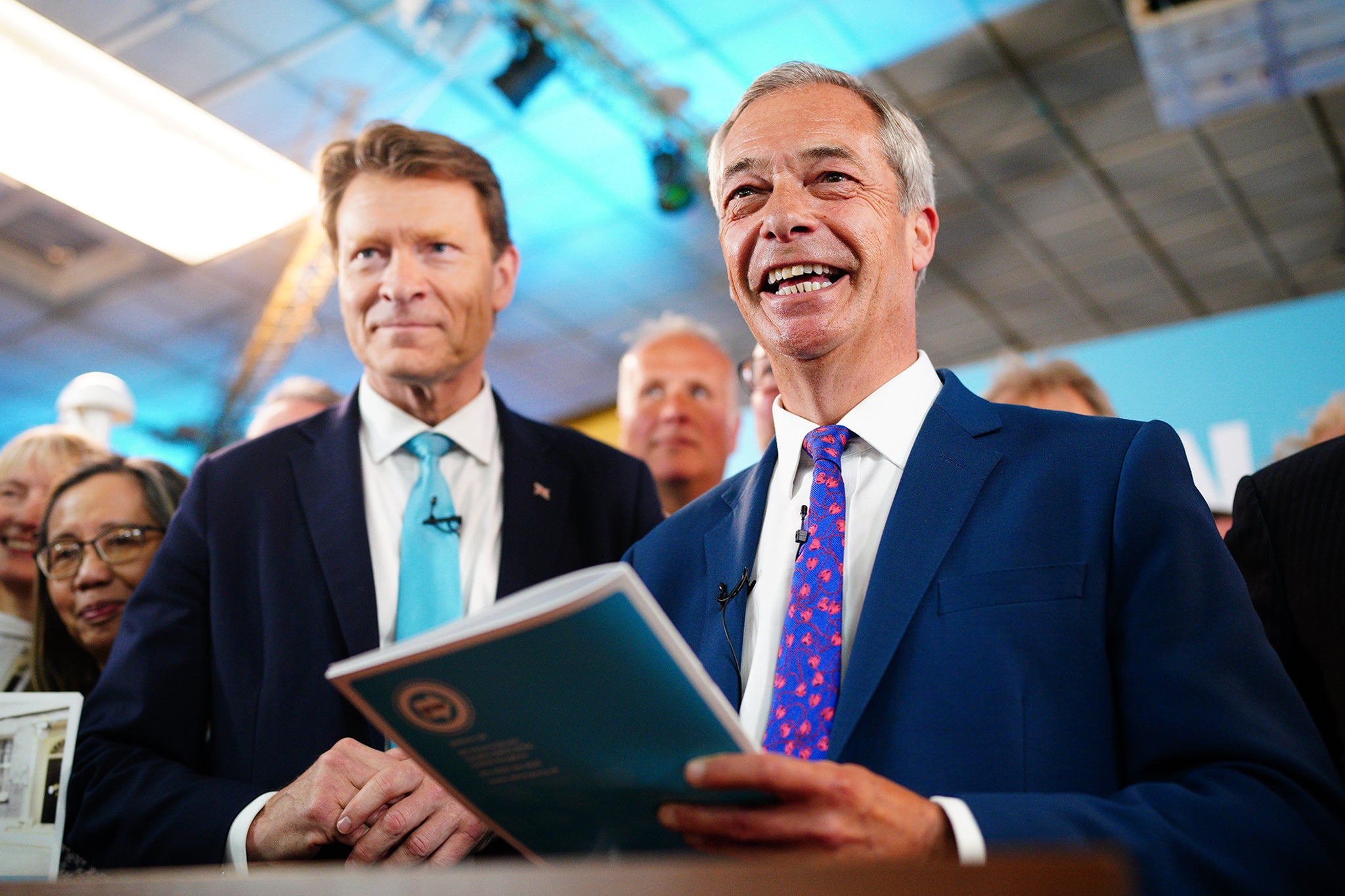

Surely Farage must know that the document he held up for the cameras is a flimsy one? He ingeniously distanced himself from it by saying it was all the work of Richard Tice, who had been allowed to be leader of Reform during the boring period while Farage was waiting in the wings for the right moment. Farage implied that it had all been put together in a hurry when the election was called unexpectedly, and therefore that no one should pay too much attention if bits of it made no sense.

One thing that is not in it, for example, is Farage’s policy on the NHS, expounded in both the seven-way TV debates. He argued that there was no point in putting more money into the failed NHS and getting worse results – we had to copy the French and adopt a social insurance system and run it “as if it was a private company”.

Yet the “Contract” proposes to put more money into the NHS and says nothing about French-style social insurance.

Never mind that, Farage seemed to be saying, as he breezily announced that the policies in the “Contract” would not be implemented because he was not going to win, but they were the “first important step on the road to 2029”.

The audience of Reform activists clapped cheerfully, oblivious to the louder cheers coming (metaphorically) from Labour HQ, where some minds were already turning to how to win the election after this one. A protracted civil war in the Conservative Party, stirred from inside the House of Commons by the wannabe MP for Clacton? Just another of the many wishes granted to Keir Starmer by his generous genie.

Picture the scene. Farage has been elected to parliament, along with probably one or zero comrades, at most six, according to the most Reform-friendly poll so far. Even if the Conservative Party has been reduced to 72 MPs, as the most Tory-unfriendly poll has projected, the leader of the Great Revolt, the extra-parliamentary “mass movement” that he spoke about in South Wales, will be vastly outnumbered – and outnumbered by Tory MPs who mostly regard him as the enemy.

He will not be the leader of the opposition, and he will not be the “real” leader of the opposition. He will be a lonely figure at the back of the far end of the opposition benches, where George Galloway, Lee Anderson, Jeremy Corbyn and Andrew Bridgen used to sit.

The “What to do about Nigel” question may continue to split the Tory party, but the prospect of a reverse takeover, of the larger entity by the smaller, will remain distant. The single most important and immutable fact about Nigel Farage is that many more voters put him in the naughty boy category than the messiah one.

With a referendum to win in 2016, Dominic Cummings would have nothing to do with him. The most that Reform has scored in an opinion poll so far is 19 per cent. Even in the chaos of the parliamentary deadlock of 2019, the Brexit Party never got consistently above 20 per cent. If the Tory party were ever to put its future in his hands, it would be locking the door to a clear majority of voters who have a fixed and hostile view of him.

The idea that Farage could be the saviour of the Conservative Party is a fantasy encouraged by a vocal group of disaffected Tories – and, I imagine, in private, by the leadership of the Labour Party.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments