Giving the health secretary greater control of the NHS appears little more than a political power play

A leak of a white paper set to be published today offers little rationale for the move. What checks and balances will be in place?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the middle of a pandemic, it would be understandable if policymakers passed on the opportunity to propose major reforms to the NHS. However, a white paper from the Department of Health and Social Care will be published today.

The comprehensively leaked draft outlines that the secretary of state has more powers of direction over the NHS and tidies up some administrative messiness left by the last set of reforms in 2012. On the face of it, the proposals will look arcane to the general population, but they could signal significant change.

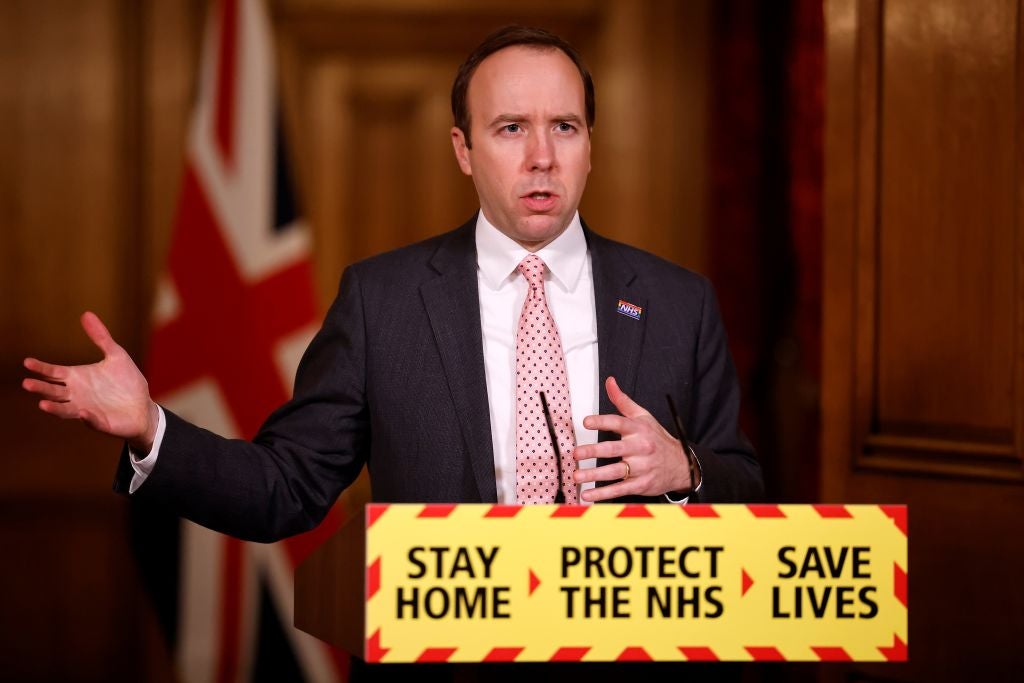

The secretary of state for health and social care – currently Matt Hancock – would have extensive new powers at a national and local level in the NHS, for example, to direct NHS England, direct local services via NHS England, and to change or even abolish national arm’s length agencies (including NHS England itself).

This is a complete reversal of the direction set by former secretary of state for health Andrew Lansley, in the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, which sought to curb ministerial interference in the operation of the NHS and confine it to setting overall strategic direction. Since the Act, the NHS has enjoyed greater relative operational independence.

Benefits have included the NHS setting its own long-term strategy via the NHS Long Term Plan, successfully mustering arguments and public pressure for more resources (the £20.5bn extra announced by former prime minister Theresa May on the NHS’ 70th birthday in 2018), and reducing random initiative-itis by ministers wanting expensive pet projects funded over more thought-through priorities.

The dangers of this potential return to “command and control” is not just excessive centralisation of England’s largest “industry”, a move of questionable benefit, but will override technical functions that require political impartiality. An example could be the way funds are allocated from the central tax pot to NHS regions within England – now carried out using a formula based on need, but of course, new funds could be directed to favour political priority areas.

It will also be important that the secretary of state does not interfere with decisions on new drugs or treatments by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). A third outcome could be interference in the quality of care ratings by the Care Quality Commission to favour certain providers. The aforementioned is unlikely, nor desirable, but it would be possible under the government’s new proposals.

The secretary of state does need some powers of direction, after all the NHS is a public service accountable to the government. And the remit of national agencies can’t always be frozen in legislation, but it does need to flex. For example, the 2012 Act makes provision for two agencies – the Trust Development Authority and Monitor – both still legally exist but have long since developed and merged into one: NHS Improvement. But the key question is what is the strong rationale for greater ministerial control, and what are the right checks and balances on an overzealous minister?

Unfortunately, the leaked draft of the white paper contains no rationale, just vague justification as “to ensure decision-makers overseeing the health system at national level are effectively held to account” and to improve accountability and enhance public confidence. The secretary of state should articulate clearly what he thinks the government hasn’t been able to do in the absence of the new proposed powers, and what he’d envisage doing with additional powers.

Contrast this to the remarks made recently by the longest-serving secretary of state for health, Jeremy Hunt, “I never felt that I couldn’t get the NHS to do what I needed it to do, and wanted it to do” within the boundaries of the current legislation.

Presenting reform to bring NHS England under closer political control may help build a narrative, ahead of any Covid-19 public inquiry, that the government is not to blame for England’s pandemic performance. But the irony is that during the pandemic, key functions under the direct responsibility of ministers and the department of health (providing PPE to social care, NHS Test and Trace) have performed disappointingly compared to many by the NHS (roll-out of vaccination, creation of surge capacity, implementation of virtual care).

The extent to which “democracy” (in the form of ministers) should trump “technocracy” (in the form of NHS England) is an old question. The rationale favouring the former in the draft proposals is at best a mystery, at worst some kind of power play by a department and ministers who have not been able to prevail by weight of argument alone, or shine during the pandemic.

As it’s currently articulated, this aspect of the proposal offers a flimsy basis for addressing the huge challenges ahead.

Jennifer Dixon is chief executive of The Health Foundation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments