The NHS has failed to learn the lessons of Morecambe Bay – with devastating consequences

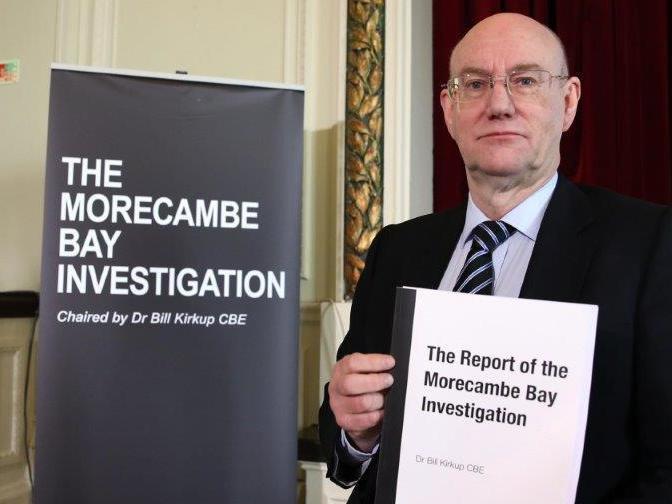

Dr Bill Kirkup, who chaired the inquiry into Morecambe Bay, gives expert insight into the leaked interim Shrewsbury report after The Independent shared it with him

The leaked interim report of the maternity review at the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital Trust was horribly familiar reading. Not because I had seen it before – I hadn’t until The Independent sent me a copy – but because there were unmistakeable parallels with previous events 100 miles to the north.

The Morecambe Bay investigation that I chaired reported in February 2015, describing tragic avoidable harm to mothers and babies. Deteriorating clinical practice had gone unseen. Maternity staff had not worked collaboratively or communicated effectively. Safety incidents had not been investigated properly or learnt from, so the same failures had recurred year after year. There had been institutional denial of problems, and missed opportunities at every level to interrupt the sequence of failure that had stretched over eight years.

Every one of those grim features is starkly evident four years later in the interim report of the review of Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital Trust.

In the Morecambe Bay report, I wrote that: “It is vital that the lessons, now plain to see, are learnt and acted upon, not least by other trusts, which must not believe that ‘it could not happen here’”. I wish that my words had not been so prescient. The lessons of Morecambe Bay were ignored in Shrewsbury and Telford, with disastrous and unnecessary consequences for mothers, babies and families. My heart goes out to them.

Since 2015, I have been told many times that Morecambe Bay was a one off; that there was only a remote chance of the same set of latent failures coming together in the same way elsewhere. Yet within a few short years “it could not happen here” has been exposed once more as simply a comfort blanket.

Two clinical organisational failures are not two one-offs: they point to an underlying systemic problem that may be latent in other units. It is vital that we recognise why, and what we can do about it. There is good evidence that some straightforward but far reaching measures would benefit all maternity units, as well as greatly reducing the chances of another large-scale disaster like these two.

First, we should make responding to clinical error part of the core curriculum for medical and nursing students. Clinicians often respond badly to making a mistake: it is hard for all of us to admit error, and even harder when someone has been harmed. Clinicians can come to believe that they and their colleagues have to be infallible, or at least to show a facade of infallibility. The result is pressure to downplay or suppress knowledge of safety incidents, instead of declaring them and learning from them. We should help clinicians to cope with error, for their own sake and their patients’ sake.

Second, we should train clinical teams, together not separately, in recognising risk and in responding appropriately to clinical problems. We know that this improves team working and improves outcomes for mothers and babies. The Maternity Safety Training Fund was shown to be effective by Health Education England’s own evaluation. It should be restored.

Third, patients and families harmed by clinical error should have the chance to be involved in their investigation. They provide vital information about what happened, they have questions that they need answering, and they need to trust that the same thing will not happen to others. One of the recommendations of the Morecambe Bay report was that the duty of candour should be extended to include a mandatory offer of involvement in investigations to those harmed. It should have been implemented.

Finally, no organisation or individual should be able to use “reputation management” as an excuse to cover up while they try to resolve problems covertly that often turn out to be beyond their capability to fix. This has become endemic in many fields, including health, and its effects everywhere are pernicious.

Honest errors that are admitted and investigated should attract neither blame nor punishment. The corollary is that concealment and dishonesty should be utterly unacceptable.

Maternity services are a vital part of the NHS. The majority do a good job that adds significantly to health and wellbeing – but when they go wrong, the consequence is tragic and unnecessary harm.

We owe it to all those harmed to think that it could happen again, unless we take action to prevent it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks