The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How the New York bombing suspect was radicalised online by a man who had been dead for five years

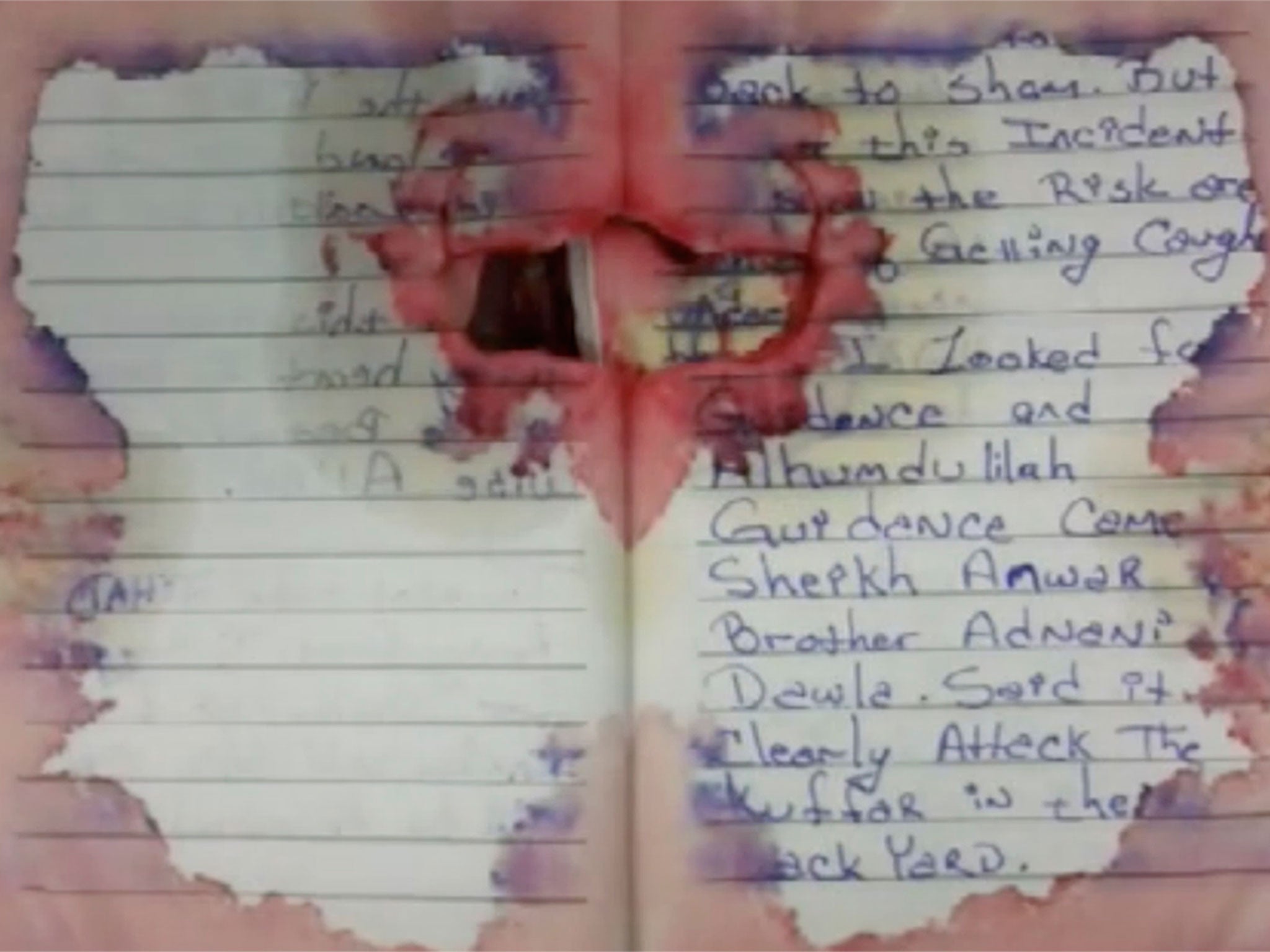

Ahmad Khan Rahami wrote in a journal he was carrying at the time of his arrest that he was looking for ‘guidance’

As the FBI continues its investigation into New York and New Jersey bombing suspect Ahmad Khan Rahami, and a picture has begun to emerge – about his background, his travels, his past and his eventual radicalisation – some of the details are worrying.

While there has been much attention placed on Rahami’s trips to Afghanistan and Pakistan and his encounters with local law enforcement officials in a New Jersey restaurant, one detail the investigators have uncovered points to the extent of the global jihadi phenomenon. Investigators discovered that Rahami was inspired by the ideas of none other than Anwar al-Awlaki, a US-born leading propagandist and recruiter for al-Qaeda who was killed in a US drone strike in September 2011. Awlaki’s links to numerous terrorist plots are well documented and his influence on potential jihadis from beyond the grave has also been noted.

Rahami wrote in a journal he was carrying at the time of his arrest that he was looking for “guidance” and answers, and ended up becoming acquainted with Awlaki’s ideas. His admission of searching for “guidance” demonstrates that it was Rahami who was seeking ideas, and that the attempt to address the gap in his knowledge was subsequently filled by extremism.

Every one of us searches for answers throughout our lives. However, in the 21st century, Muslims are increasingly asking questions about Islam online rather than at the mosque or through other religious institutions. The starting point for almost all enquiries about matters of faith is the internet search engine.

Five years since Awlaki was killed, the ideology he espoused continues to proliferate online. Supposedly mainstream Islamic websites – sites purporting to present genuine Islamic content – are in fact hosting lectures, videos and publications from leading jihadi ideologues. This terrifying content is hiding in plain sight on websites that may, at first glance, seem to be quite ordinary, providing free access to the Quran or Hadith.

Our research found there are almost 20,000 web searches each month for Anwar al-Awlaki – a demonstration of his continued influence. Moreover, the explicitly jihadi English-language publications produced by al-Qaeda, in which Awlaki featured regularly, are also accessible via a simple search. Anyone with an internet connection can stumble across it.

Rahami’s actions – just as with Omar Mateen in Orlando, and Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik in San Bernardino – are a violent manifestation of a set of hate-filled ideas presented under the guise of religion. The violence is the unfortunate symptom of a much deeper challenge, the Salafi-jihadi ideology. Attacks in France, the US, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Nigeria and Somalia, carried out by Isis, al-Qaeda or others of their ilk, are bound together by a vision of the world that only recognises “believers” and “unbelievers”; one that sees the world divided into right and wrong, black and white, and in which a select few must wage war against the very nations in which they have been born, raised and educated.

Jihadi violence, while sporadic, is not whimsical. An individual must accept the ideas, values, and objectives of this violent, barbaric interpretation of jihad before committing acts of violence. In this sense, stopping the spread of these ideas must be the focus of our efforts to dismantle Islamist terrorism.

Recent attacks in the West have shown how, once that worldview is accepted, anything and everything can be weaponised. Rahami is reported to have bought supplies for his bombs from eBay, while Omar Mateen purchased his gun over the counter legally in the US. Elsewhere, in Germany and France, we saw the use of knives and a truck.

Discussions on countering terrorism online are often overcomplicated with discussions about the dark web and the sophistication of the bad guys. The truth is that they are not sophisticated. They are, however, highly determined.

Considerable efforts have been taken to remove extremist content from the web, however focusing on the danger of the dark web and social media isn’t enough. We have to understand the religious and civic concepts that extremists manipulate to propagate their own ideas. Banning and taking content down will only take us so far. Only by understanding the appeal and reach of these ideas will we be able to successfully defeat them.

The onus of this task rests not only on the shoulders of technology companies but governments and civil society. All must show a greater determination and conviction in this global battle of ideas.

Mubaraz Ahmed is an analyst for the Centre on Religion and Geopolitics at the Tony Blair Faith Foundation. Follow him on Twitter: @MubarazAhmed

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks