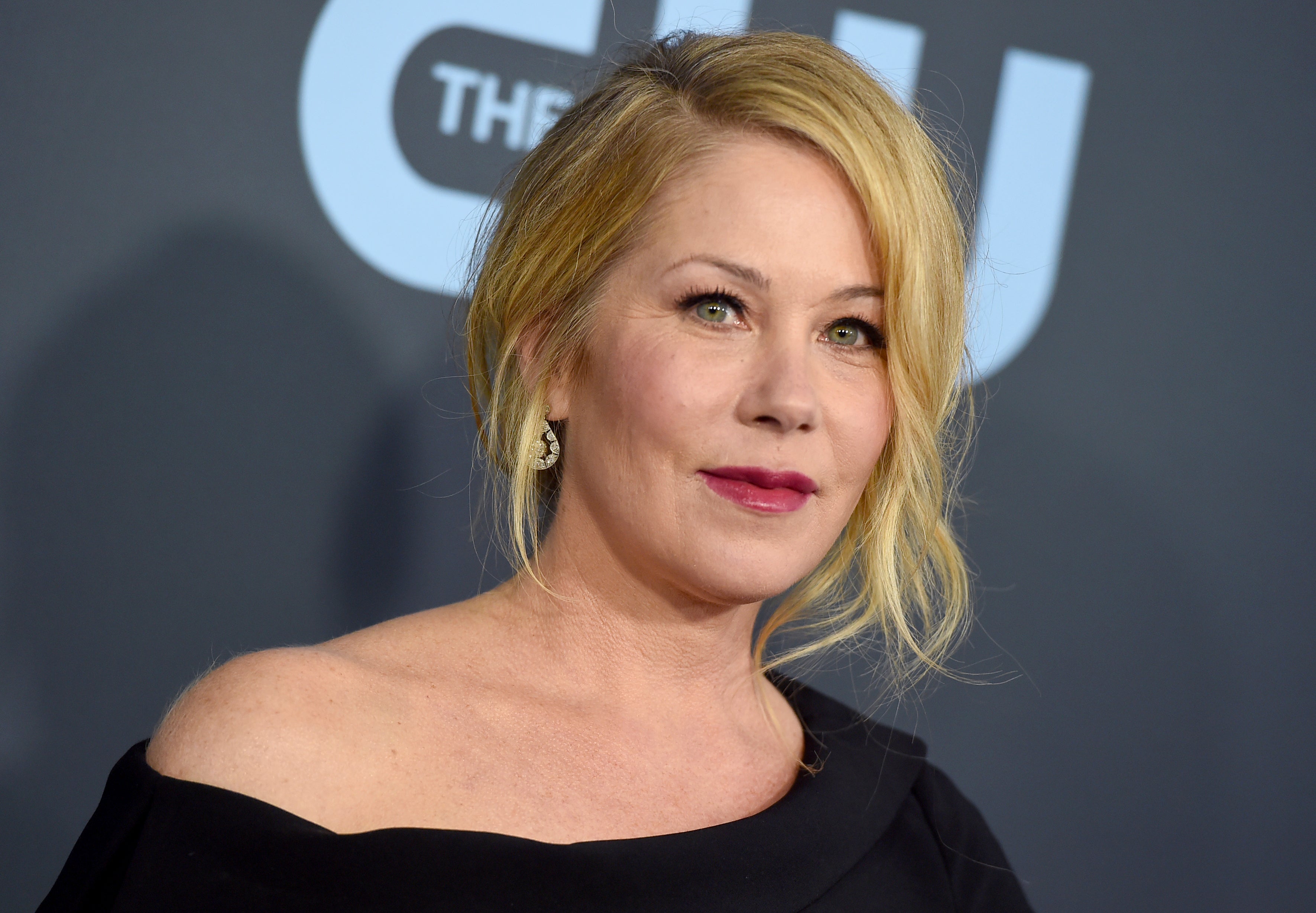

An MS diagnosis can be lonely – that’s why Christina Applegate’s bravery going public is so significant

Women are three times more likely to get multiple sclerosis than men. Influential women talking about their MS can help eradicate stigma and encourage others to seek treatment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People with disabilities navigate a hostile world at times. One of inaccessibility and stigma. Those of us with multiple sclerosis (MS) are often deprived of the joy of participating because we are told we are “unable” to do certain things. Or we hold ourselves back for fear of discrimination. The courage it takes to reveal having MS to others can’t be underestimated, which is why actress Christina Applegate announcing her recent diagnosis and star Selma Blair highlighting the gritty side of living with the disease is so significant.

MS is often thought of as being an older person’s disease, yet it is predominantly diagnosed in young women and we are three times more likely to get MS than men. Influential women talking about their MS can help eradicate stigma and encourage other women to seek treatment and share their stories.

MS is a progressive neurological disorder affecting the central nervous system. The immune system turns against itself by attacking the protective layer of the nerves, which causes lasting damage in the form of “lesions” or scar tissue. This can result in a huge range of symptoms from vision and mobility loss to cognitive impairment and spasms. It is incurable, but there are ways we can mitigate progression through lifestyle changes, diet, exercise, and medication. The majority of people like myself are diagnosed with relapsing remitting MS, which is dictated by periods of new or worsening symptoms, interjected by intervals of recovery. A more debilitating form of MS, known as primary progressive MS is usually diagnosed in people in their 40s and 50s and can have a significant impact on mobility.

There tends to be a misconception that if you have an illness, you somehow caused it, reinforcing damaging stereotypes. Yet, like so many diseases, MS is genetic, switched on by external factors. The hidden cost of stigma around MS is enormous. A study done by the MS Society showed that one in three people in the UK choose not to disclose their MS, with one in 10 even hiding it from their partner. Nearly 60 per cent of respondents kept their MS from their colleagues for fear of discrimination. This is because those of us with MS are far less likely to be hired as we are considered less productive. We are typecast as incapacitated, which is why so many choose to keep it a secret. Although concealing MS can prevent discrimination it is also incredibly stressful, and can significantly impact our overall health. It also makes it harder to create a support system.

When I was first diagnosed with MS, I blurted it out to anyone I spoke to like uncontrollable word vomit. It was as if I were talking about somebody else. The “sick” part of my body wasn’t really me. I forged on in complete denial for the first six months, despite being hindered by the pendulum of symptoms and persistent fatigue that accompany MS. The impossibility of keeping up the façade of “wellness” resulted in multiple A&E visits. After gallons of steroids gave me cheek flanges like a baby orangutan, I was forced to confront my illness. Cognitive dissonance for those of us with chronic illness is inevitable, especially when first diagnosed. This is particularly true for those of us with the relapsing remitting form of MS, as most of the time the symptoms associated with this are invisible initially.

The debate over whether to share an MS diagnosis is centred around able-bodied being the status quo. Our sense of self-worth is often influenced by societal norms, determined by our abilities to do certain things. There is a fear of disability, it is seen as unwanted, a deviance. Society discriminates against those who are different physically and/or neurologically through “ableism” – systemic bias against disabled people. It’s often so subtle that most people don’t even realise they are doing it, myself included. We often internalise our ableism, not wanting to be seen as disabled or othered, so we mask our illnesses or disabilities. Since I don’t look visibly disabled, I downplay a lot of my symptoms. I felt that if I shrugged it off as not really a big deal, people wouldn’t react with pity painted on their faces as if I were somehow broken. This ultimately results in some people dismissing my MS as not being “that bad”. MS is unpredictable, which is hard for people to grasp.

We are made to feel that disability is something to hide like the remnants of last night’s kebab or dirty laundry. This plays out through accessibility and how people with disabilities are catered for in day-to-day life and social situations. It’s also in the language we use. For example, words used to tell people about our MS, like “disclose”, “come out”, “admit”, have undertones of shame. In the media we are rarely represented and when we are, we tend to be portrayed as the living epitome of trauma or else the stories are about how people have “overcome” their MS, or are championed for being “warriors”, often simply for existing. Negative stereotypes are so deeply entrenched, our accomplishments must therefore be an exception. More inclusive language can be created if we involve people with disabilities in forming these narratives.

MS isn’t a dirty word. It’s part of life for millions of people. It is hard to take pride in a disability that takes away parts of you, but acceptance is essential for healing. It can be a lonely journey, but through it you also create strong connections, build resilience, and develop an immense understanding of self. And, for that, I am proud.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments