Michael Buerk's criticism of celebs like Cumberbatch 'pratting' round with good causes was short-sighted

It would have been easy for these well-meaning celebrities to remain in their bubbles of money, glamour and privilege and to turn away from poverty, conflict and misery. The fact that they didn't shouldn't put them in the firing line

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Buerk’s powerful reporting of the Ethiopian famine in 1984 is one of the most famous news stories of the past 50 years. It is well known as the inspiration for Live Aid, but it also ignited interest in news reporting for a generation of future journalists – including my 10-year-old self. Buerk’s report – drawing the world’s attention to an unreported story – is what any journalist aims for. It is a testament to the legacy of that 23 October 1984 report, that the majority of us fall short.

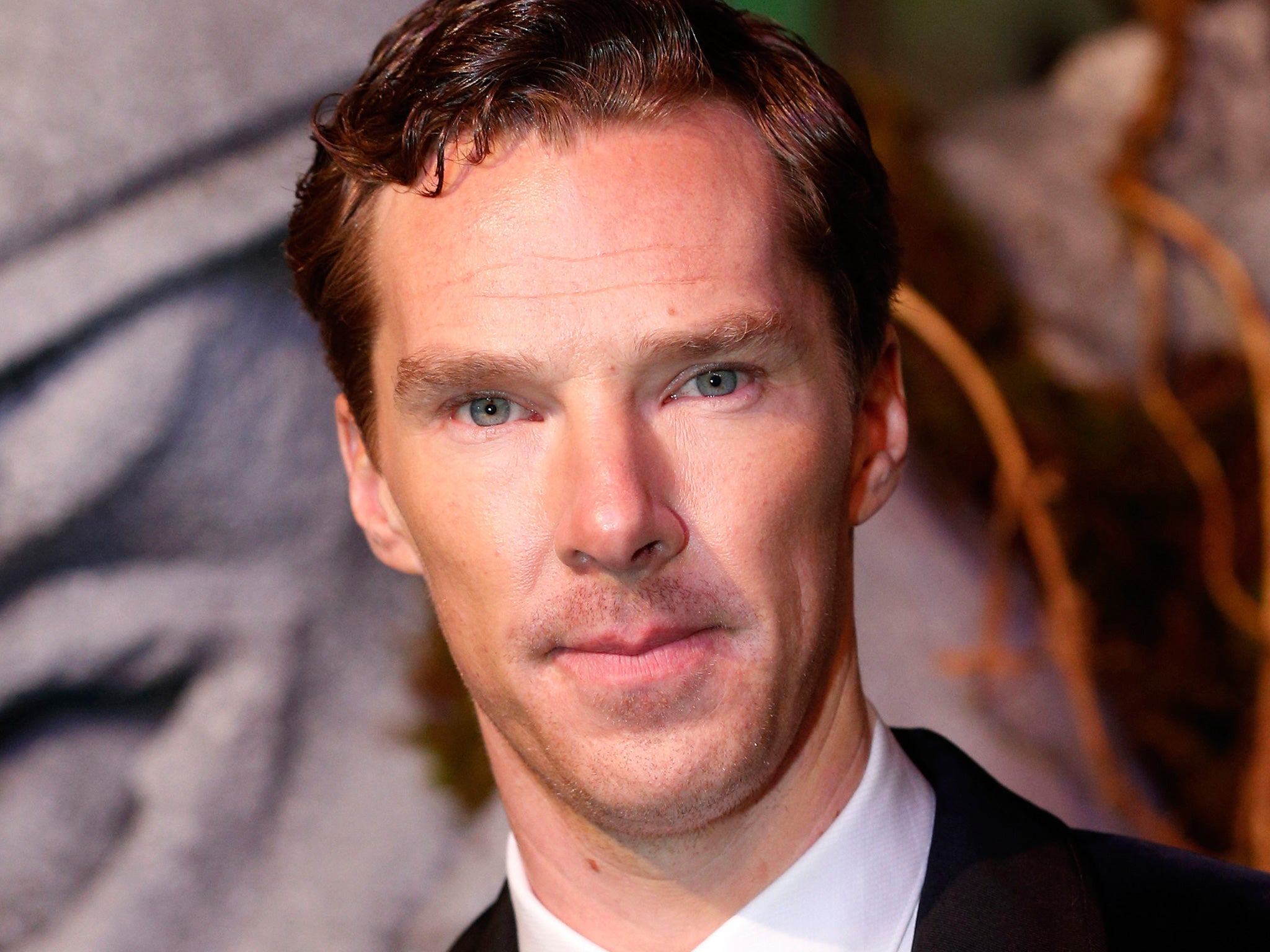

So I can see why the veteran BBC journalist has let rip against celebrities such as Emma Thompson and Benedict Cumberbatch for joining political campaigns and protests. He has told the Radio Times: “As a superannuated war reporter myself I’m a little sniffy about celebs pratting around among the world’s victims. I hate it when feather-bedded thesps pay flying visits to the desperate to parade their bleeding hearts and trumpet their infantile ideas on what ‘must be done’. There’s only so much of the Benedict and Emma worldview you can take.”

I can see why Buerk is irritated by these actors, with all of his experience in conflict reporting. But in this instance he is wrong.

It would be easy for Thompson, who has protested with Greenpeace against Shell drilling for oil in the Arctic, or Cumberbatch, who during a recent performance of Hamlet urged the audience to donate money to Syrian refugees, to remain in their bubbles of money, glamour and privilege and to turn away from poverty, conflict and misery. Just as it would be easy for Emma Watson, a multi-millionaire at the age of 25, to simply carry on making films instead of launching the hugely successful HeForShe initiative as a UN ambassador for gender equality. When Leonardo DiCaprio raged against climate change in his best actor acceptance speech at the Oscars last month, he was attacked for taking a plane across the Atlantic two weeks earlier to pick up the same award at the Baftas (what was he supposed to do, take a gigantic passenger liner from Southampton? We know how that ends).

Instead of remaining mute-but-beautiful, these actors are using their status to raise awareness. They know the huge followings they have, and the power of adding their faces and voices to a cause. Who are they harming by declaring that something “must be done”? Is it really “infantile” to be angry about the world’s problems? So many of us, celebrities, journalists and citizens alike, are impotent against war, famine and climate change. Yet if you can prick the conscience of one politician, or inspire one person to take up the cause, isn’t that better than retreating into a world of Hollywood parties and fortified mansions?

Journalism can be a heroic trade – as shown in the Oscar-winning film Spotlight – and nothing can replicate the powerful reporting of its practitioners. Journalists such as the BBC’s chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet, currently reporting from Syria, get under the skin of a story in a way that no celebrity can. It can mean days or weeks of filming, interviewing, challenging authorities, risking your life and, in some cases, dying to tell the story.

But people know the difference between a war report on the 10 o’clock news and celebrity backing for a cause. And, like it or not, actors and musicians can reach beyond viewers of evening news bulletins into a wider audience. Would the world have been as aware of the representation of Native Americans in the US if Marlon Brando hadn’t asked Sacheen Littlefeather to make a speech on his behalf at the 1973 Oscars? Would war-zone rape – tragically an issue as old as the human race – have received as much coverage if Angelina Jolie hadn’t been the figurehead for a campaign to end sexual violence in conflict, leading a summit in London with William Hague in 2014? For all the rhetorical abilities of the then Foreign Secretary, his voice alone would not have drawn the same degree of attention.

And what of Band Aid and Live Aid, the fundraising single and concert inspired by Buerk’s original report that in turn made my generation – and each one since – aware of poverty and famine around the world? Four million people watched the BBC News on 23 October 1984, but Live Aid on 13 July 1985 was watched by 400 million worldwide. Buerk has to accept that even the most hard-hitting of news reports can only do so much.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments