After the detention of Meng Wanzhou, Trump’s trade war with China is an immediate danger to what remains of global prosperity

Since China decided to rejoin the world economy in the 1990s, the country and America have become like two drunken giants staggering down the street – and now the pair have fallen out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where does the biggest threat to global security lie? Forget Iran, North Korea, Isis, Saud Arabia, even Russia; it is starting to look like China – or, rather, China’s troubled and rapidly deteriorating relationship with the only other economic superpower that rivals it, America.

On some measures China’s national income is already more than America’s. It matters, but we pay far less attention to Beijing than Moscow.

However you weight it, it is the badly faltering Sino-American partnership that is really troubling financial markets – far more than Brexit, for example, or the Russian designs on Ukraine. The US-China trade war, specifically, is the thing threatening a global recession, with all that that entails. For we all know that economic slumps are usually incubators for turning populism and nationalism into extremism, and dictatorship and wars.

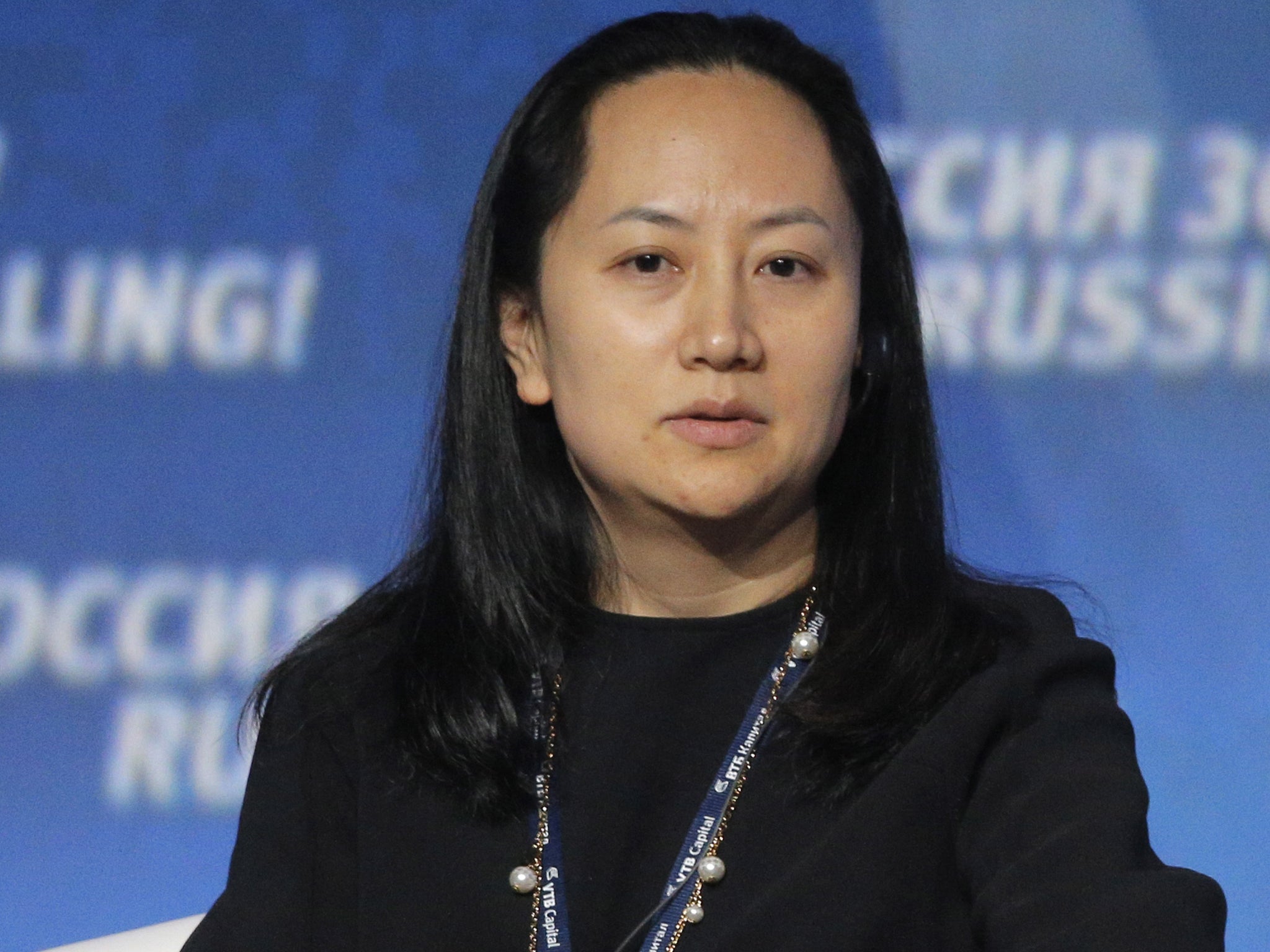

That is why the arrest of a Chinese businesswoman in Canada is so worrying. She is Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s chief financial officer. More than that, she is the daughter of the founder of this Chinese telecoms giant, a matter of some symbolism. She has been detained in Vancouver at the behest of the US authorities who, it is reported, think she has been involved in busting US sanctions on Iran. China says her human rights are being violated.

It was always going to happen. Some business figure, bank or company would end up targeted by the Americans, given that the US blanket global ban on economic contact with Tehran stretches way beyond Washington’s proper jurisdiction. What is telling is that the Americans have decided to hit such a high-profile individual from China.

Wanzhou helps run a company that is an emerging global force and which has already been the subject of discriminatory practices in the west. Such is the sensitivity around telecoms, satellites and security that the US, Australia and New Zealand have blocked the use of the Chinese firm’s equipment in infrastructure for new faster 5G mobile networks. In a very rare public speech, the head of MI6, Alex Younger, said that the UK had to make “some decisions” on Huawei. His was a highly unusual and frank admission of western paranoia about China: “In China they have a different legal and ethical framework … They are able to use and manipulate data sets on a scale that we can only dream of.”

Yes, but why would they wish to?

China has territorial ambitions over the offshore Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and across the South China Sea, where it has been creating artificial islands to back its legal case for sovereignty. It has been indulging in wars of words and gunship diplomacy against its smaller neighbours (Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia) and their allies, including the US Navy and the Royal Navy. China also, of course, has a long-standing grievance over Taiwan, and has been interfering in Taiwan’s politics for some time. The Beijing-Pyongyang relationship is also one that has not always served the cause of world peace or allayed America’s concerns. Western complaints about human rights, Tibet, Hong Kong and Chinese neo-colonial acquisition of land and resources in Africa also annoy President Xi and his cohorts, justified though some may be.

Yet these are, mostly, regional squabbles, and, for the moment, hardly threaten our vital interests. Indeed, China has legitimate complaints left over from the time when it was a weak, fractured state exploited by western powers and, in due course, annexed and pillaged by imperial Japan. If the Chinese are a little nervous about their position in the world, they have some right to be – they suffered a “century of humiliation” from the Opium Wars of the 1840s through occupation and to the communist revolution in 1949.

A multi-power conference to settle these interlocking post-colonial and (to the ousted world) obscure disputes would go a long way to dissolving tensions. Reuniting Taiwan with the mainland is, frankly, long overdue – a relic of China’s pre-Mao past and the days when “Red China” was a geopolitical threat to the US (with proxy wars in Korea and Vietnam failing to settle their differences).

And who exactly is starting this new cold war with China? The US vice president Mike Pence made a landmark speech at the Hudson Institute recently, followed up by hostile remarks at the Asia-Pacific summit last month, that constituted a virtual declaration of (cold) war on China. For example: “I come before you today because the American people deserve to know… as we speak, Beijing is employing a whole-of-government approach, using political, economic, and military tools, as well as propaganda, to advance its influence and benefit its interests in the United States. China is also applying this power in more proactive ways than ever before, to exert influence and interfere in the domestic policy and politics of our country.”

However, it is Donald Trump’s trade war with China, currently in a state of confused and uneasy truce, that represents the clearest and most immediate danger to what’s left of global prosperity.

The president is correct in asserting that, over a long span, the Chinese have manipulated their currency and their economy towards a successful policy of export and investment-led high growth, and one that has seen the US run up significant debts with the Chinese. The Chinese, in turn, are now sitting on a vast pile of US Treasury paper – IoUs – to the tune of some $1 trillion.

Superficially, this quantity of dollar assets – around a tenth of America’s entire national debt – gives China leverage over America. In reality, however, any attempt to “dump” the debt on markets to retaliate for US policy would most likely backfire badly, shredding the value of China’s reserves.

Such was the concern over the issue that, a few years ago, the US Defence Department was asked to assess the strategic implications of this pile of US bonds. The conclusion? “Attempting to use US Treasury securities as a coercive tool would have limited effect and likely would do more harm to China than to the United States. As the threat is not credible and the effect would be limited even if carried out, it does not offer China deterrence options, whether in the diplomatic, military, or economic realms, and this would remain true both in peacetime and in scenarios of crisis or war.”

Nonetheless, the long-running US-China trade relationship, lopsided as it is, has been and remains the most serious of the many “global imbalances” that led up to the 2008 financial crisis and its painful aftermath – the creation of so much US debt (money, in other words), fuelling the US mortgage boom, the phenomenon of the mortgage-backed security and the tottering tower of paper that threatened the entire global financial system.

Since China decided to rejoin the world economy in the 1990s, America and China have become like two drunken giants staggering down the street, each dependent on the other for export earnings (China from America) and loans (America from China). Now the two drunks are starting to argue and fall out. The current trade talks between them are a faint hope of a much broader overhaul of their mismanaged economic relationship. In essence, China needs to marketise and liberalise its economy so that resources are not misallocated to pointless “prestige” investment and infrastructure projects and towards boosting household consumption; and America needs to accept that the reason why Chinese stuff is so cheap is because they have a lot of people and wages are necessarily low. America needs to export more – to China, Japan, Germany and other surplus nations by being more competitive; China simply needs to spend its reserves and buy more imports.

As with Japan before, the US’s trading relationship can be reformed and normalised, but the US is no longer the most efficient and highest productivity economy in the world. Protection of outdated industries will not help the US move forward. The trade deficit, in other words, is also partly America’s fault. Both sides need to take long-overdue action to fix it – but not tariffs and quotas.

China gets nowhere near the coverage Russia gets, which is wrong. Aggressive, revanchist, arrogant, sliding towards dictatorship, engaged in real, proxy, espionage and cyber wars everywhere from the Sea of Azov to Salisbury – yes, Russia is a volatile power. It is true that Vladimir Putin is a threat to world peace and his, shall we say, complicated relationship with Trump is only adding to the unstable mix. And yet Russia’s importance, if not its ambitions, is often overrated, much to the Kremlin’s satisfaction. For Russia is, in economic, industrial and financial terms, a pygmy punching way above its weight thanks to the mesmerising effect of its few large corporations – almost always in basic, raw materials and energy sectors and its high-profile, multi-billionaire oligarchs. In reality, Russia’s national income is about the same as Indonesia or Germany, and only one fifth of that of America, China or the European Union. It is a Potemkin superpower.

Russia, for sure, has a large military, though poorly equipped, and the defence budget is only as large as the UK’s or France. The Russians are more dangerous than the Chinese, yes, but not as potent a threat as we often fear. Mismanaging our relationships with Putin cannot push the west into an economic depression.

A cold war with Russia, then, is one thing; a cold war with China would be far more ruinous for far more of the west’s citizens.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments