Mea Culpa: the torture of the English language

Horse- and hare-based metaphors, and other changing usages, in this week’s Independent

We had an outbreak of amiditis this week, a common journalistic affliction. “Amid” is a short word that can be used to link two things without being specific about the connection between them. So we often see it in headlines, but it is one of those words that is more useful to the writer of headlines than to the reader of them.

This week we had: “May fails to find Brexit customs compromise amid cabinet divisions.” That reads oddly, because it implies that the prime minister was trying and failing to draft a compromise in the cabinet room, while ministers squabbled around her about unrelated subjects.

What the news report said was that she had failed to find a compromise that would hold together her divided cabinet. The headline should have said something like that.

We also had a headline that read: “May says ‘no place for bullying’ in parliament amid Bercow claims.” There we meant “in response to”, which might have been cumbersome in a headline, so perhaps something like “as new Bercow claims emerge” would have been better.

In foreign news, meanwhile, a fascinating dispatch was undersold with a clumsy “amid” in the headline: “The Unesco-protected ‘Jewel of Arabia’ vanishing amid Yemen’s civil war.” It was about the island of Socotra, which is geographically not “amid” the civil war at all, although it has been affected by it. A simple “in” would have sufficed here.

Horse-based metaphors: We had “free reign” a couple of times this week. I suppose it makes more sense in a society no longer dependent on horses, but it was originally “free rein”.

This raises, as this column so often does, the question of when a form of words that was originally a mishearing or a misspelling should be accepted as standard. My view is that, as long as there are a significant number of readers who think the new form is wrong, we should avoid it. Perhaps these distinctions shouldn’t matter, but it is not in our interest to put off readers for no good reason.

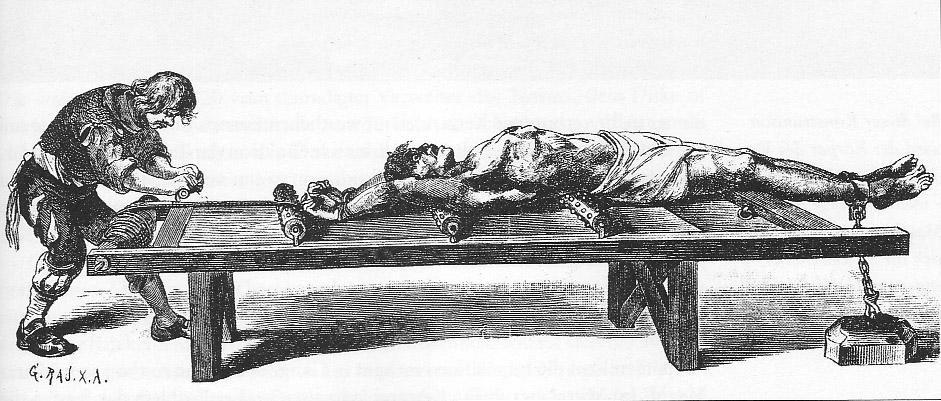

Instrument of torture: The same goes for “nerve-wracking”. We quoted someone using the phrase this week and spelt it thus, with a “w”. The phrase was originally “nerve-racking”, from the metaphor of torture by being stretched on a rack. As this hasn’t been a common practice since the 17th century, it is surprising that it has survived in the language so long, and not surprising that its spelling has varied.

What is odd about the “wrack” spelling, though, is that it is an equally old-fashioned word, a variant of wreck, used to refer to ships. And those who hold the w-spelling to be a mistake are undermined by the Oxford Dictionary: “Figurative senses of the verb … can, however, be spelled either rack or wrack.”

The Oxford adds: “The phrase rack and ruin can also be spelled wrack and ruin.” This is more justifiable, I think, because the sense of “wreck” is stronger. For example, we reported on another suicide bomb in Kabul this week, saying Afghanistan is “still regularly wracked by violence”. Did we mean “wrecked” or “tortured” by violence? Probably both.

Timetable for bombings: My problem with saying Afghanistan is “regularly wracked by violence” is not the “wracked” but the “regularly”. Regularly implies something that happens at fixed intervals, whereas we meant “frequently” – something that happens a lot.

March hares: Finally, wrack and wreck are related to wreak, and in a review of children’s books we wrote about Ada Twist, a character who “wreaks havoc with her hair-brained experiments”. Wreaking havoc is fine and good fun, but hair-brained was originally hare-brained, referring to strange behaviour of hares in spring, when they leap and twist in the air. That is a better, and more evocative, phrase.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks