Mea Culpa: Little letters

Susanna Richards rounds up our errors and omissions in last week’s Independent

A reader kindly wrote to say that we had used the wrong word in a report about wildfires when we said that “they are now erupting with unprecedented size and ferociousness in new parts of the world as the climate crisis worsens”. The contention was that we ought to have said “ferocity”. Actually, I rather like “ferociousness”, and the Oxford dictionary recognises it as a word in its own right, with exactly the same meaning.

Our correspondent was right about something else, though, noting that we had described a type of smoke particle as “miniscule”. That’s technically an incorrect spelling, though an extremely common one: it should be “minuscule”, from the Latin minuscula meaning “somewhat smaller”.

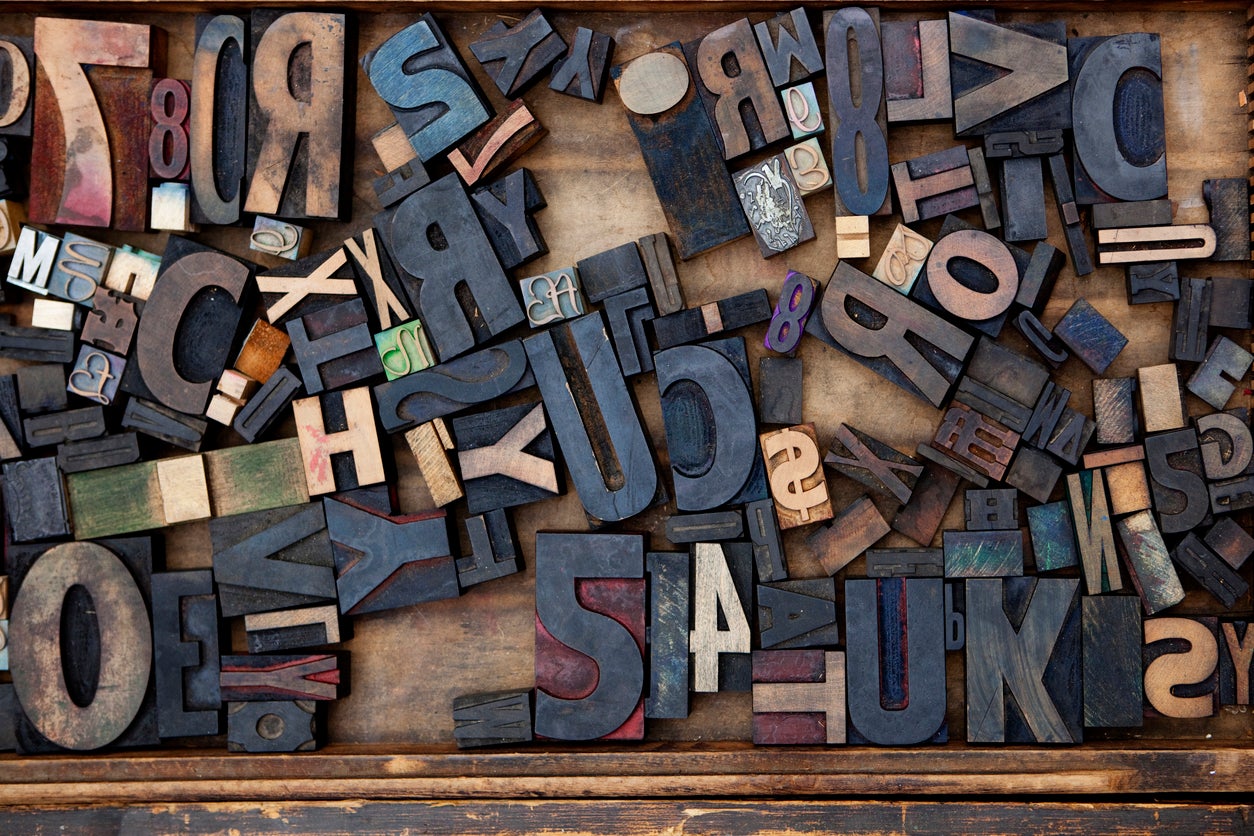

Its etymology is rather lovely, in fact: as a noun (derived from the adjective) it refers to letters in the lower-case alphabet, which developed by degrees from the 7th century AD, and in particular to their use in moveable type; their upper-case counterparts are called majuscules. So I think we owe it to our forebears in the printing (and manuscript-writing) industry to get it right, even though the variant spelling is widely considered acceptable.

Now and then: When we are writing about events from long ago – or even not that long ago – there are several ways to describe a person who was something else at the time, but we often get it wrong. In the past week we have written about the “then-home secretary Theresa May” and “the then-levelling up secretary Michael Gove”, and they are probably not the only ones to have been over-hyphenated.

The reason that it’s wrong is not that it’s especially liable to cause confusion; no one is going to think that a “then-foreign secretary” is a secretary who was once foreign but isn’t now. It’s because it compels the conscientious reader to go back over what they have just read in order to make sure that it means what they think it does. This makes reading less comfortable than it would otherwise be.

The correct way to write something like this is either to leave out the awkward hyphen – “the then secretary of state Hillary Clinton” – or simply to phrase it in a different way, as we did in one of our long reads, which said: “It was Caro Quintero, then the leader of the Guadalajara Cartel, who US officials say ordered Camarena’s kidnapping.” Much clearer, much simpler, and much less distracting, allowing the reader to concentrate on the story.

On the bench: “It is relatively easy to replace worktops, and substituting tired laminate or rotten wooden countertops for something more durable will give your kitchen a fresh, design-led feel,” we wrote in an article about cutting the cost of renovations. It is difficult to use the verb “substitute” correctly. When you substitute something for something, you replace the second thing with the first thing, which isn’t, I think, what was intended here. We changed it to “substituting ... with”, though that formulation is frowned upon by some. I think “replacing with” would have been a better fix.

In the same article, we said: “Kitchen islands and other worktops serve as impactful platforms for refreshing your kitchen’s design scheme.” Impactful? Regular readers will be aware of the long-running campaign by the owner of this column against the use of “impact” as a verb, but I’m not sure if this isn’t even worse, especially combined with “platforms”. We could just have said that changing these elements was “an effective way” of refreshing the design.

Raising the stakes: We slipped up last week when we reported some comments made by a politician, who described eradicating racism as something that “requires hard, pain-staking cultural challenge”. While it’s fundamental to our journalism that we quote speech (or writing) as accurately as possible, we permit minor adjustments to be made for clarity, grammar and spelling, if it can be done without changing the meaning or tone.

It’s quite a neat error, though: “painstaking” is normally one word, not two, and it doesn’t need a hyphen. It’s formed from the phrase “taking pains”, meaning that if it did have a hyphen, it would come after the “s”. But it’s easy to see how one might think otherwise. I suppose “staking pain” isn’t that implausible a concept, in the sense of a struggle to achieve something important despite the risk that one might not succeed.

Typo of the week: In a review of last Sunday’s Conservative leadership debate, we wrote: “Sunak vs Truss did an excellent job of bringing their own personal band of mean-spirited and vitriolic loathing to the small screen.” This conjured a vision of the two candidates, surrounded by demonic musicians, grinning as they revile one another in the medium of song. I’m told that, in fact, this image is not significantly more horrifying than what did take place.

Roll on September.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks