Mea Culpa: Rack and ruin

Matters of style and usage in last week’s Independent, compiled by Susanna Richards

Our perplexing insistence on using the wrong word prompted one of our regular readers, Roger Thetford, to inform us that we had once again said “wracked” when we meant “racked”.

He is right, of course. The two words are frequently used interchangeably, but as Roger suggests, each spelling, with its corresponding etymology, makes sense in a specific context. Thus, when we want to suggest that the government is being pulled this way and that by various scandals, “racked” – from rakken, early 15th century, meaning “to stretch out” – is the obvious choice, while something that has been destroyed might be better described as “wracked”, which probably comes from the Middle Dutch word wrak (late 14th century) meaning “wreck”. I (w)reckon that covers it.

Lest is more: In an editorial that talked about freedom of expression, we quoted someone saying that companies could find themselves in a position in which they had no choice but to take down online content that might be “perfectly harmless, less they face sanctions, penalties and even personal arrests for getting it wrong”. That should be “lest” – a lovely old word that is described by the Oxford dictionary as a “negative particle of intention or purpose”, which, though it sounds quite exciting, is another way of saying it doesn’t really have a category. It is always used in the subjunctive, as in the well-known idiom “lest we forget”, which comes from a poem by Rudyard Kipling.

Another language website notes that “particles do not change”. If only the same were true of our familiarity with words like “lest”. It may be formal, and old-fashioned, and its use has been declining for years, but I hope it won’t be forgotten entirely.

Promised land: In a report on the Miami Grand Prix, we wrote: “If anything was to symbolise F1’s heady assentation from what was largely a bit of a niche and nerdy interest 20 years ago to an unmissable occasion …”, and no, none of us has any idea what an assentation is, so thanks to Paul Edwards for letting us know it was there. Here at the Indy we feel that “ascension” has rather heavenly overtones, so we changed it to “ascent”.

Inquire within: In an article about Sir Keir Starmer and the curry-related trouble he is in, we managed to use the word “probe” no fewer than three times. First we talked about a “police probe into a takeaway meal with colleagues”, which conjured up an image of a uniformed officer carefully poking a scientific instrument into said takeaway to test it for compliance. Then we said that we didn’t know “what additional details [had] sparked the probe”, which added an electrical dimension to the picture. And lastly we noted that the “so-called ‘Beergate’ probe” could take up to six weeks. That is a long time to be leaning over a plate of curry with a pointy thing, I think.

Anyway, of the three instances, two were replaced with “inquiry”, and one with “investigation”, which I hope cleared things up, at least on the linguistic front.

Talking of Beergate, there does seem to have been an abundance of “gates” recently. Watergate, the scandal that generated the trope, took place some 50 years ago, and as such the use of this suffix to signal a public controversy or fuss ought perhaps to have gone the way of Nixon’s presidency by now. But it shows no sign of slowing down: there have been dozens in the past few years alone. As such, I suppose we are stuck with it, though it may transpire to be rather apt in the case of Partygate, given that, according to some assessments, the prime minister is in deeper water for the alleged “cover-up” than for the alleged “crime”. But that is a matter for the pro – er, inquiry.

Call the cops: Finally, in an article about a yacht that was thought to belong to Vladimir Putin, we wrote: “In March, the ship’s British captain, Guy Bennett-Pearce, denied that Mr Putin had ever owned or stepped foot on the Scheherezade.” The phrase “step foot” is widely thought to be a misinterpretation of “set foot”, and perhaps it is – or was originally – though a closer read of my favourite language forum reveals that it has been in use since at least the early 1800s, and possibly the 1500s: a sort of lifelong companion to the version most often used.

Sources note that it is mainly the preserve of US English now, and given it appears far less frequently in print than “set foot”, we changed it to that.

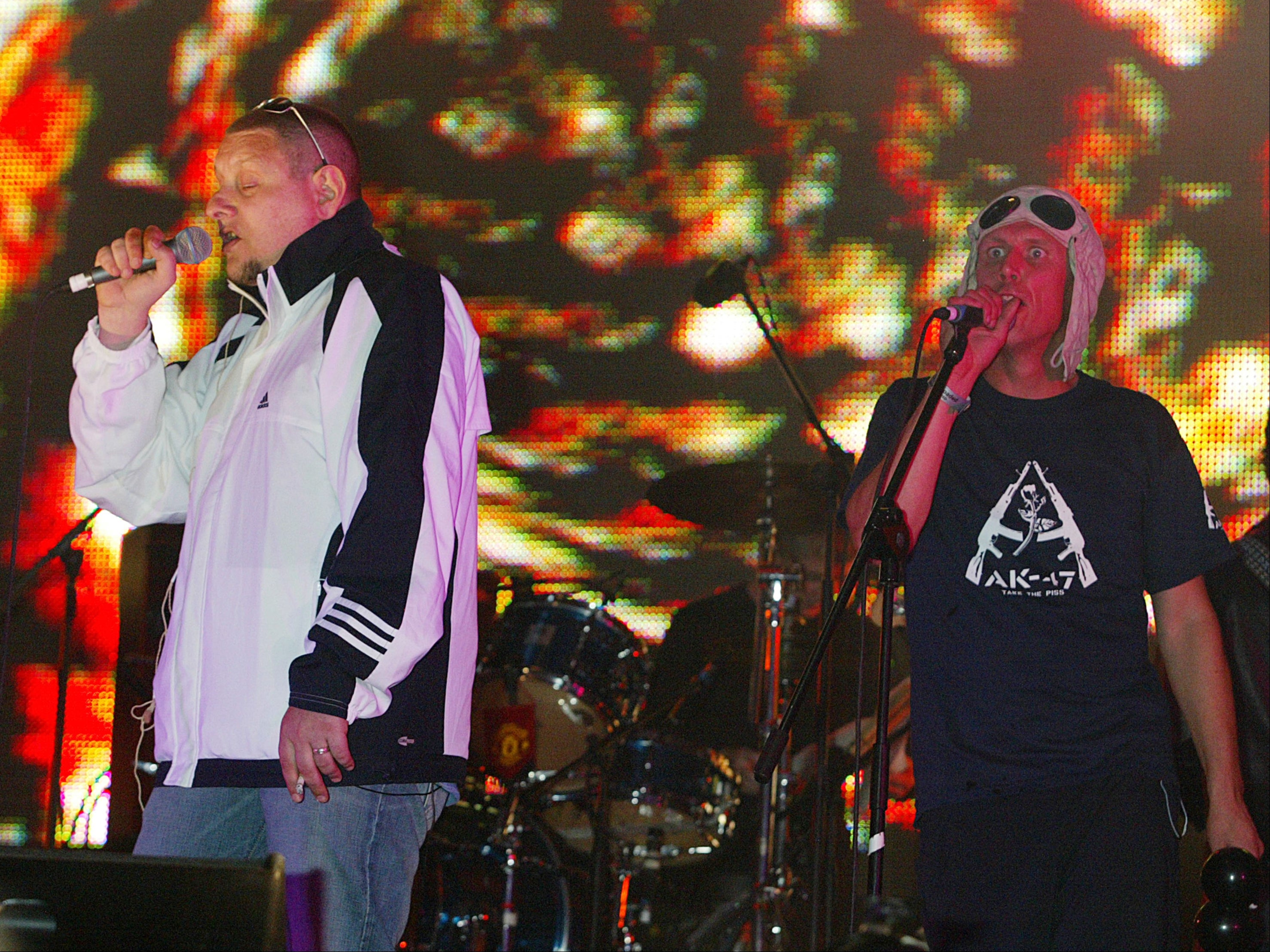

In any case, I think the “set” version makes more sense. “Step” is an intransitive verb in the context, meaning it doesn’t require a direct object: that is, it isn’t done to something. So we step, but we don’t step our feet. In most instances, you have to say “step on [a thing]” – and you need to mention the thing, too, unless you are the title of a Happy Mondays song. We at The Independent do not, as it were, talk so hip.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments