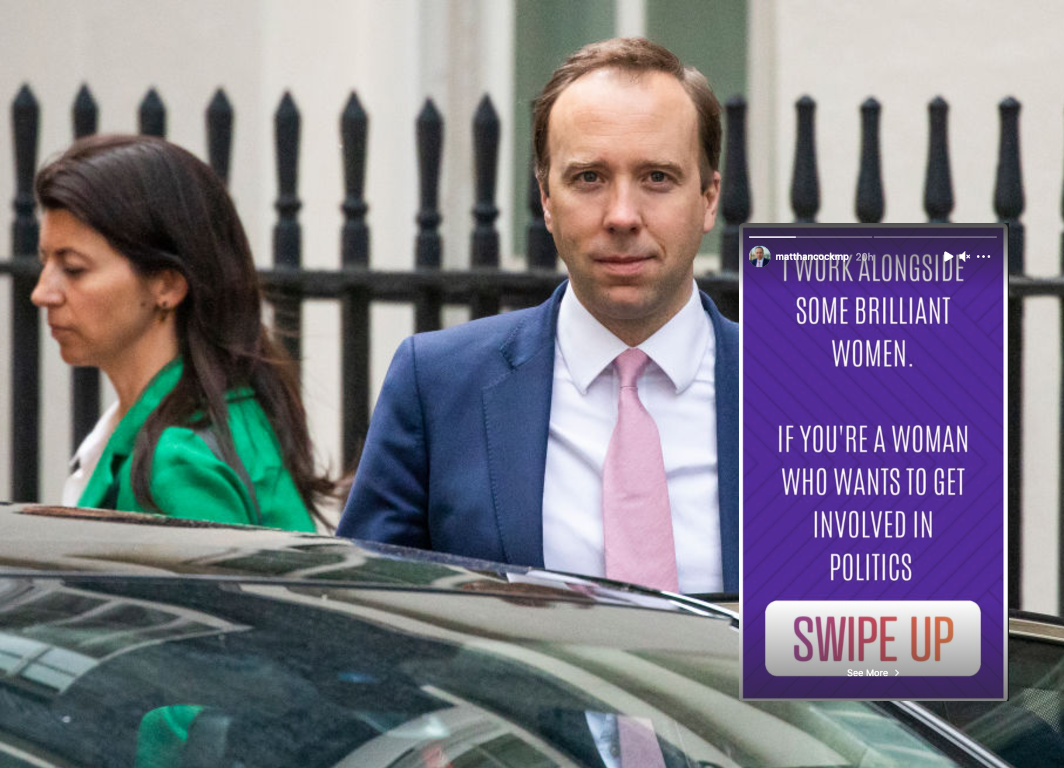

There would be a very different kind of backlash if Matt Hancock was a woman MP accused of an affair

Women continue to be judged through a different lens compared to men – gender raises the ethical bar

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As I read news of Matt Hancock’s alleged affair this morning, and the tweets about it, which very quickly turned into jokes and memes, I couldn’t help but wonder if women are judged more harshly when it comes to affairs, especially women in the public domain.

Yes, men are over-represented in powerful political positions, and so they likely outnumber women when it comes to affairs, too. Some might suggest that women are probably too busy carrying the emotional and mental load at home to have the time to have affairs. This could very well be the case – but it might also be that they are more fearful of the harsher repercussions they are likely to face if their affair became public knowledge.

That’s because women continue to be judged through a different lens as compared to men. A study by Ashley Madison, the world’s “leading married dating website” in 2019 – called The Good Wife Study – showed that a staggering 92 per cent of women (from a total of 2,066) believe they face worse and more frequent criticism than men for stepping outside of their marriage and conducting an affair.

Women are also knowingly underrepresented in politics – according to a UK House of Commons briefing paper from March 2019, there were 209 women members of the House of Commons. At 32 per cent of the membership, this is an all-time high, but still not enough. In May 2019, five cabinet members (22 per cent) were women, and the prime minister was also a woman until June 2019.

The highest proportion of women in Cabinet was 36 per cent between 2006 and 2007. So, it isn’t anywhere near a level playing field just yet – and it doesn’t take much to imagine how the few would be judged by the mighty for any perceived transgression. Gender is emphasised more for women politicians, and they are often regarded as novelties or trivialised while their male counterparts are portrayed as the norm.

The Bem Sex-Role Inventory, created by psychologist Sandra Bem in the 1970s, categorises descriptive language into masculine, feminine, and neutral groupings based on how individual words are perceived by the public. Bem found that words like “ambitious” and “assertive” have been associated with masculinity, while words such as “compassionate” and “loyal” have been associated with femininity.

The stereotype is that women are supposed to be more loyal, but also that they do not naturally make good leaders – which means that they are judged more harshly for being disloyal. They also have to work much harder to prove their credentials in the political domain at senior level.

In an excellent 2011 article in the New York Times, journalist Sheryl Gay Stolberg rightly noted that it is often easy to dismiss men’s transgressions as, “a testosterone-induced, hard wired connection between sex and power” – as powerful men attract women. On the other hand, powerful women repel men, since they are seen as stepping outside the typical feminine stereotypes: which is seen as a sort of unacceptable transgression in itself.

This is not the first time a male politician’s transgressions have become public news; and in this way it has become somewhat normalised. Women, on the other hand, are held to higher moral and ethical standards. Gender raises the ethical bar.

According to a 2014 Pew poll, 34 per cent of people surveyed believed that women in high-level political offices were more honest and ethical than men. And, in a research study, volunteers were told about a hospital administrator who deliberately filed a false health insurance claim. Half of the group was given a woman’s name (Jane) while the other half a (more commonly) man’s name (Jack), and all the other details were completely identical. The recommended sentence by the two groups was around 80 days for Jack, and around 130 days for Jane – harsher punishment for the same perceived offence.

In another study, on analysing 500 cases across 33 states in the USA of a lawyer being disbarred, it was found that women had a 106 percent higher likelihood of being disbarred than men for similar offences.

The ideal of higher moral and ethical standards – plus loyalty – might seem like benevolent stereotypes, but they are nevertheless stereotypes, and such positive norms can also be harmful.

People judge bad decisions less harshly when it is by those who are in gender-appropriate roles; and even the language in our biology and medical textbooks, and in sex education classes is

heavily gendered. Heterosexual female sexual pleasure is never placed on an equal par with male sexual pleasure. A male orgasm is discussed in many textbooks; a female orgasm is only ever mentioned in the context of its value to transporting sperm or aiding fertilisation, views that were held in the late nineteenth century and earlier but have since been debunked.

The failure to acknowledge female orgasm beyond its role in fertilisation reinforces the myth that women have much lower libidos than men, and that any sexual aggression and misdemeanour on the part of a man is because of his naturally higher sex drive, thereby absolving men of responsibility for their actions.

Ultimately, it is true that women have always been castigated for their sexuality. Men, on the other hand, are excused as “boys will be boys”. We continue to live by these rigidly imposed societal ideals, and any mistakes come at a much higher cost for women.

Dr Pragya Agarwal is a behavioural scientist and her most recent book (M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman is now out with Canongate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments