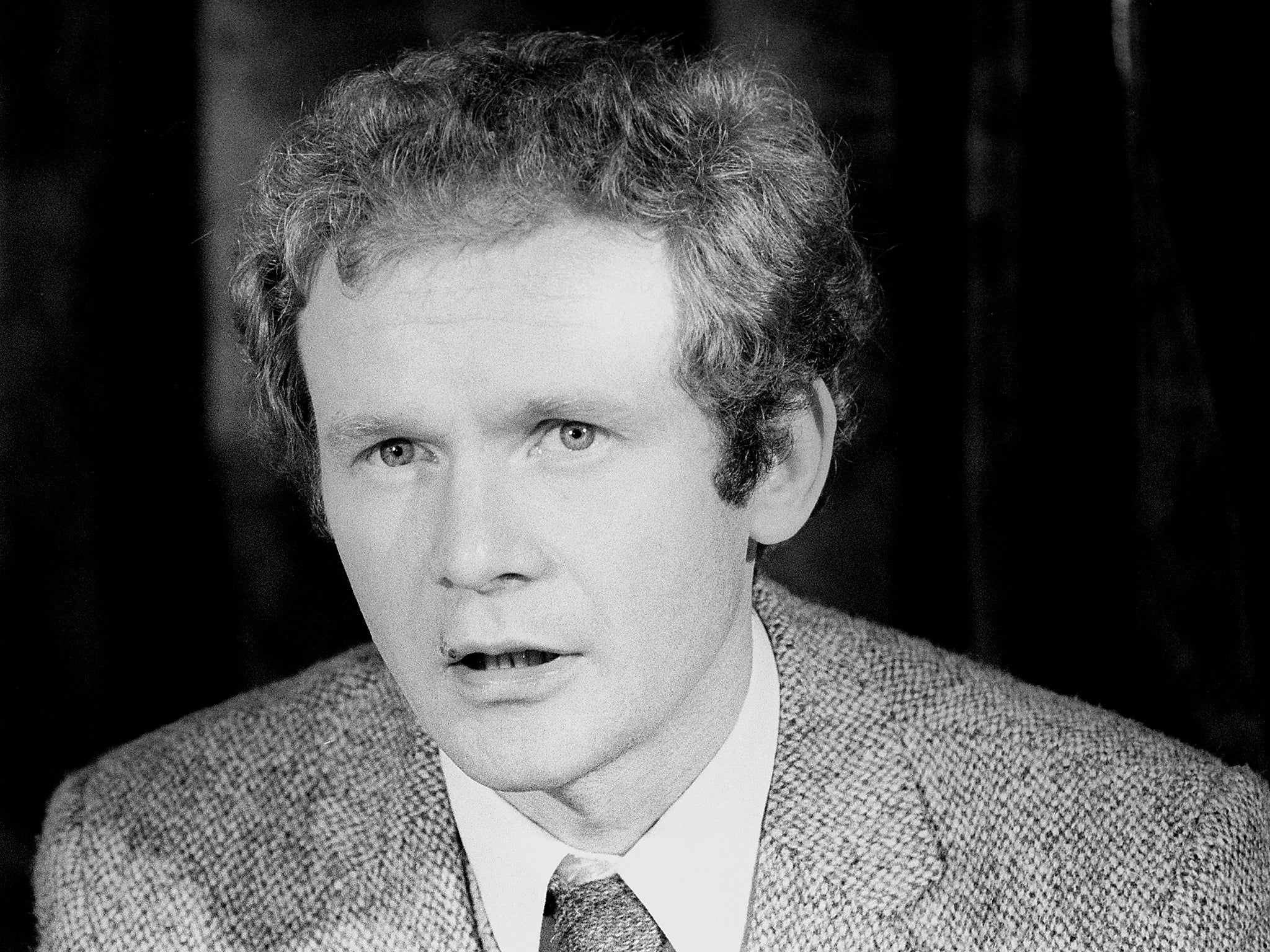

Martin McGuinness dead: From adolescent acid bombs to a political giant of the peace process

Statesman led a dramatic life, experiencing three decades of violence before embracing political solution and declaring ‘my war is over’ in 2002

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Although Martin McGuinness was for decades deeply involved in violence, he was brought up in a non-violent household in the family home in one of Londonderry’s overcrowded Catholic ghettos.

His family was well-regarded and known for religious devotion: his parents went to mass every day, and each evening they and their seven children said the rosary together in their home, which had two bedrooms and a scullery but lacked a proper kitchen.

But the late Sixties brought the outbreak of the Troubles, and one day a local priest came to Peggy McGuinness to tell her that her son Martin had been caught stealing acid from his school. She was, she said, embarrassed and ashamed.

But this was no mere adolescent prank. McGuinness intended to use the acid in bombs to hurl at the security forces in the rioting which involved hundreds of local teens.

Far more unwelcome news was to come later for Mrs McGuinness, when she was shocked to find that her son had hidden gloves or other paraphernalia in the house.

“It immediately traumatised her,” McGuinness recalled. “She did not hit me with it or anything like that, or if there were gloves there was no smack across the face with the gloves.

“I think that it was a moment in time and she was obviously annoyed at the prospect that all of our lives were changing and maybe mine more dramatically than anybody else’s.”

Neither mother nor son could have had any idea of just how dramatic McGuinness’s life would be in the IRA, Sinn Fein and politics. Three violent decades lay ahead for him before he publicly declared in 2002: “My war is over.”

By 1971 he had become fully radicalised and, after spending a few months preparing pre-packed meats in a local butcher’s shop he became a full-time street fighter. By the age of 21 he was second-in-command of Londonderry’s fearsome IRA.

Frequent arrests and interrogations had no impact on a man later described by a Royal Marine major as excellent officer material.

Even with limited manpower and resources in the early IRA, he proved a major danger to life and property.

His unit was heavily outnumbered and outgunned, as he was later to describe in evidence to the tribunal investigating the deaths of Bloody Sunday. He had 40 or 50 volunteers, he testified, mostly in their early 20s, though he said thousands of people ready to help in different ways.

They had ten rifles of various kinds, he said, plus “half a dozen short arms, and perhaps two or three sub-machine guns”.

They had titles such as explosives officers and intelligence officers but, he explained: “We accorded ourselves these grand titles which bore very little relationship to the reality. All of us were very young – we were not like a conventional army, we were not well organised, we were making it up as we went along.”

He spoke, with a trace of regimental pride, of the skills of his gunmen, telling the tribunal: “A number of British soldiers were killed in what were known as single-shot sniping situations. The IRA had a small number of people who were probably more accurate in their sniping than the average British soldier, and a number of British soldiers lost their lives.”

He did not clarify whether he himself was one of the snipers, but at another time he related being “fired at by the British army on countless occasions over 20 years”. It seems highly unlikely that all those bullets were going in one direction.

In fact the statistics show that his IRA in Londonderry, although facing hundreds of troops, killed 27 soldiers during 1971 and 1972. At the same time its bombing teams laid waste to much of the city centre, one observer describing central Londonderry as looking as though it had been bombed from the air.

In his evidence to the Bloody Sunday tribunal McGuinness had no hesitation in displaying detailed knowledge of IRA tactics. He would have regarded it as an awful waste, he explained, to use nail bombs against armoured military carriers. “The sole purpose of nail bombs,” he said, “was for them to be used as anti-personnel devices, maybe where soldiers would have got out of a vehicle.”

The IRA was much troubled by informers, he added, and there were many occasions “when people who betrayed republicanism went over to the British, and were executed by the IRA”. The background, he told the tribunal, was “a state of war between the IRA and British military forces”.

As for McGuinness’s involvement on Bloody Sunday, the tribunal concluded he was probably armed with a sub-machine gun, but that there was insufficient evidence to judge whether he had fired his weapon. He hotly denied that he had.

A few months after Bloody Sunday he had his first taste of high-level – in fact cabinet-level – politics. Northern Ireland Secretary William Whitelaw secretly arranged for IRA leaders to be flown to London for an exploratory meeting.

The republican delegation, which included McGuinness and Gerry Adams, was driven in a blacked-out van to a helicopter, then flown to London by RAF plane. It was a formative experience for a young Bogsider who had been brought up in a house without a modern kitchen.

“I was 22 years of age, and I couldn’t be anything but impressed by the paraphernalia surrounding that whole business, and the cloak and dagger stuff of how we were transported from Derry to London,” McGuinness recounted.

“At the military airfield in England we were met by a fleet of limousines. They were the fanciest cars I had ever seen in my life: it was a most unreal experience. We were escorted by the Special Branch through London.”

Their destination was Cheyne Walk, the plush Chelsea street which had at various times housed figures such as Lloyd George, Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Paul Getty, George Eliot and Diana Mitford.

If the idea was to overawe McGuinness and the others it failed. He pronounced himself completely unimpressed, later commenting: “The only purpose of the meeting with Whitelaw was to demand a British declaration of intent to withdraw. All of us left the meeting quite clear in our minds that the British government were not yet at a position whereby we could do serious business.”

At that point he wrote off the idea of relying solely on political negotiation, remaining committed to the idea of pursuing victory through violence. Decades were to go by with many more people dying before he became committed to a purely political path.

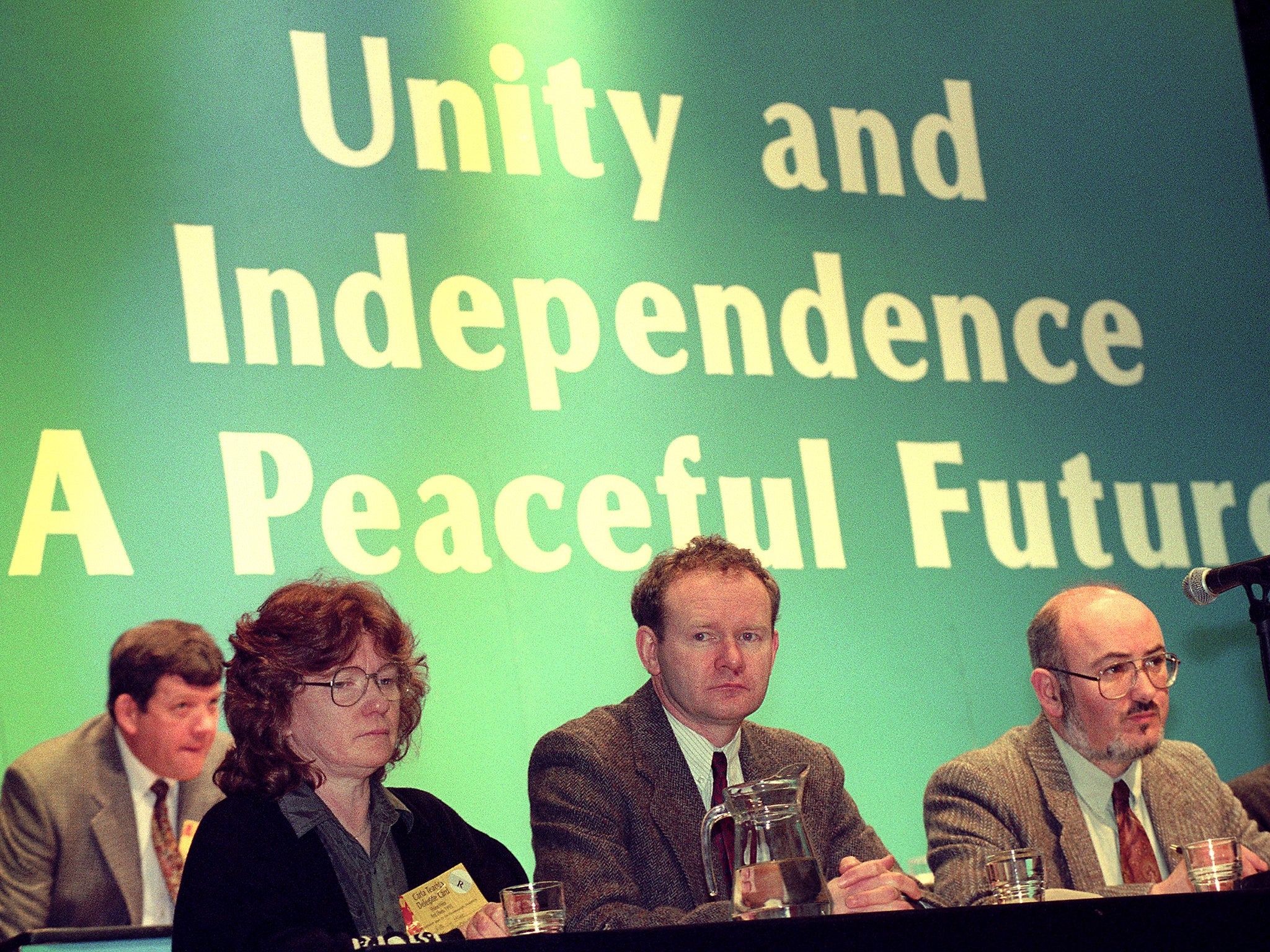

The idea developed among the leadership of the IRA however that its aims could be pursued by a mixture of politics and the gun, a theory that came to be known as the Armalite rifle and ballot-box strategy.

It was coined by McGuinness’s associate Danny Morrison, who declared at a Sinn Fein conference: “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?”

Working closely with Adams, he deftly staged a remarkably peaceful coup against traditional IRA old-timers.

In a key intervention at a republican conference McGuinness pointed to the old guard and declared: “They tell you it is an inevitable certainty that the war against British rule will be run down, that Sinn Fein and the IRA are intent on a constitutional path. Shame – shame – shame. Our position is clear and it will never, never, never change: the war against British rule must continue until freedom is achieved.”

McGuinness and Adams won the vote and from then on took control, so once again the conflict went on. Much later however they were, with infinite caution, to steer the republican movement away from violence and into politics, eventually running down the IRA and building Sinn Fein into a highly effective political machine on both sides of the Irish border.

They set about reorganising the IRA for the long haul, adopting a strategy known as the long war. It was partly reorganised into a cell structure in order to tighten internal security and guard against the effects of informers and interrogation. It also widened its range of targets, killing a number of senior business figures and prison staff, and smuggling in powerful new weaponry.

At the same time as the Troubles dragged on, McGuinness developed a new role in the very grey area between violence and politics which ultimately came to be known as the peace process. To calm doubts among the militant IRA grassroots that Adams might be turning into too much of a peacenik, McGuinness, with his reputation for implacable militancy, played a key role in providing assurance to hardliners.

Designated as Sinn Fein’s chief negotiator, he took part in years of negotiation with British intelligence officers, officials and eventually ministers, giving vital cloud cover to Adams’s pragmatic compromises.

And finally he devoted the last ten years of his life seeking to build peace, having evolved from the young lad making acid bombs at the start of the Troubles to the political figure working to bring the conflict to a close.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments