It's not the internet that's destroying local news – it's greed

When they're gone we’ll be left with a huge hole in the free speech society we value so much

In May 1989 I walked into a newsroom for the very first time. I was 19, and on the Friday I had completed a one-year pre-entry course run by the National Council for the Training of Journalists at what was then Preston Polytechnic. On the Monday, I started work at the Chorley Guardian for the princely sum of £83 per week, before deductions.

It felt somewhat like coming home. It was a weekly paper, serving a small Lancashire town, but there were reporters, photographers, newsdesk secretaries, chief reporters, sub editors, news editors, an editor… and that was just in the editorial department. It felt like I was embarking on a career. It felt, crucially, like a job for life.

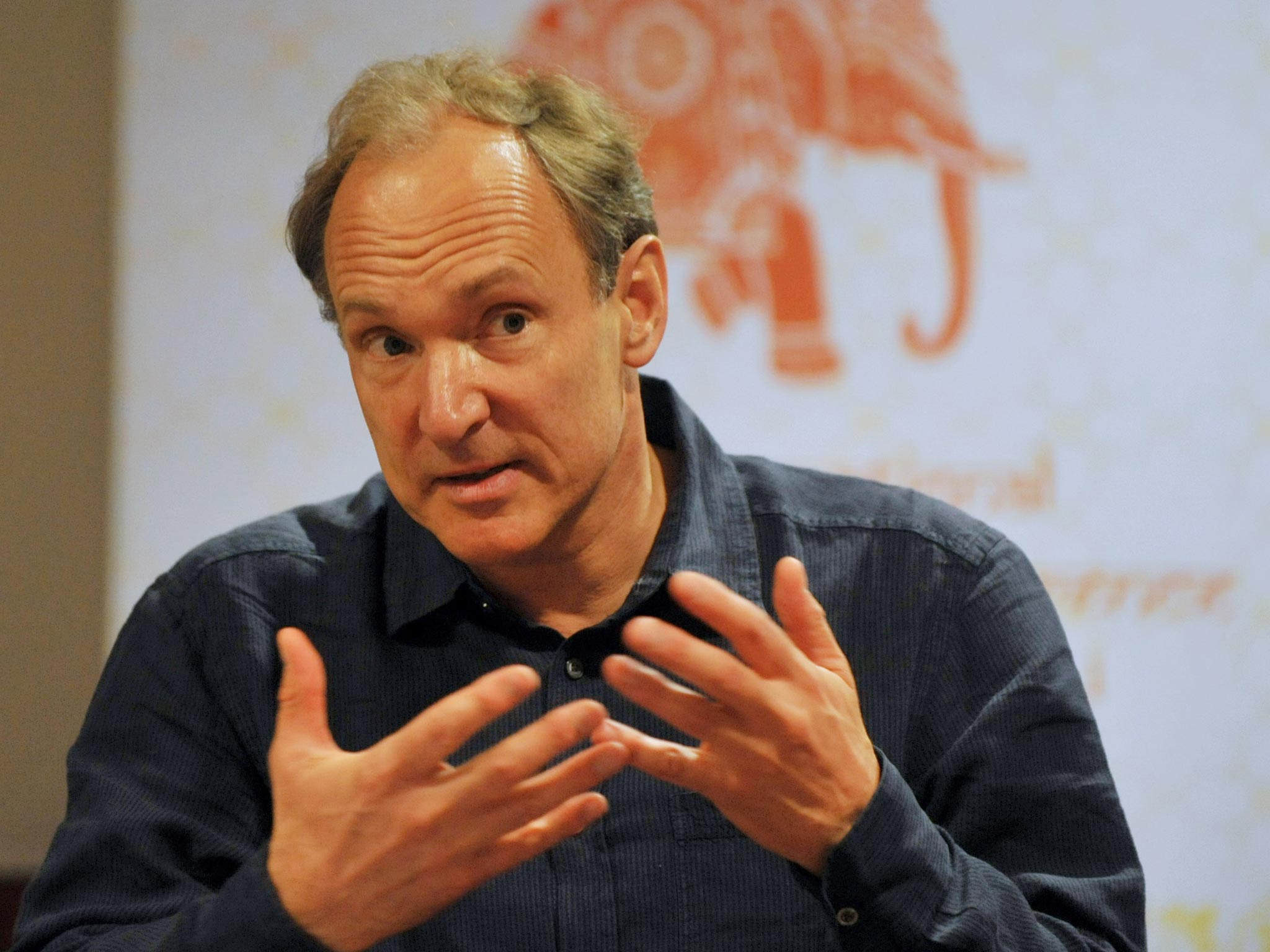

Unbeknown to me and, I imagine, everyone else in that room, right at that moment a chap nobody had ever heard of called Tim Berners-Lee was setting in motion an irrevocable revolution. He was a computer scientist at Cern, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research in Switzerland, and a few weeks before I started my first job Berners-Lee submitted a proposal to his bosses about “the management of general information about accelerators and experiments at Cern.” It discusses the problems of loss of information about complex evolving systems and “derives a solution based on a distributed hypertext system”.

Berners-Lee had just conceived of the internet. A quarter of a century later it would indirectly lead to me discovering that newspapers were not, in fact, a job for life, as I was told my position was redundant.

Popular wisdom tells us that the internet has all but killed local newspapers. But while it might have hastened their demise, that’s not really the whole truth. The local press is not quite dead yet, and while it might be hanging on to the edge of a precipice, it isn’t really the internet that’s stamping on its fingers. It’s greed.

Last week a campaign was launched by the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) called Local News Matters Week. It’s entirely possible, unless you work in the industry, that this completely passed you by. Next month, from 15 May, the annual Local Newspaper Week begins, which serves to highlight the power of the press working in local communities. It’s generally something trumpeted in your local newspaper. If you’re among the growing number of people who no longer – or have never – bought your local paper, then it’s probable that this, too, will not feature on your radar.

You might be of the opinion that physical newspapers are an irrelevance in the modern age, when information travels far and fast. If you’re reading this, it will be online; the irony is not lost on me. But I stress again: the internet is not the enemy of newspapers. It’s simply another medium of delivering relevant content, albeit one that the local news industry has somewhat struggled to embrace and keep up with. If print newspapers are going to die – and depending on which forecast you read that will be between five and ten years hence – it is, rather curiously, their owners who will hammer the last nails in the coffin.

Another story for you. Some years after I first walked into that newsroom I reached a position at a different title where I was expected to attend meetings to discuss the future of newspapers. A slight aside here: local papers must be one of the only industries where if you excel at a job you are taken off it and given a new role. The best reporters inevitably get on a trajectory that sees them put on to newsdesks, and thus on the slippery middle-management pole, even if their skills lie in news-gathering and writing and not in admin, management and filling in time sheets or conducting appraisals.

I was once told, while bemoaning the fact that my time was taken up with these non-journalistic practices, that while I was considered one of the best writers that particular newspaper had, there was simply no way that a good writer could expect to be paid the wage that a middle-management pen-pusher would get. A curious state of affairs for a business built on the written word. I would apologise to all the local press snappers for that last sentence, but as far as I know they’ve all long been made redundant in favour of reporters armed with iPhones and constant pleas for readers to send in their own photos of events or incidents.

Anyway. At that meeting I voiced an opinion that local newspapers were actually a public service. I was greeted with an aghast silence and a comment that, “What do you think we are, fucking binmen?” before discussion turned back to how best to save money and maximise profit. So I felt somewhat vindicated last week when Helen Goodman MP, chair of the NUJ all-party parliamentary group, told the House of Commons during a debate calling for a Government inquiry into the state of the local media that “We need to get back some better control of the way newspapers are run and to restore the idea, which was most recently voiced by [former The Sunday Times editor] Harry Evans, that journalism is a sort of public service. This isn’t purely a commercial enterprise – it’s also a public service.”

Because I still strongly believe that. You might laugh at the @CrapLocalNews Twitter account with its photos of bills and filler copy proclaiming how firefighters were called because someone mistook a hat in a tree for a cat or how thieves stole a wheelie bin, but who else is doing what the local press is doing? Who else is promoting that coffee morning to raise money for a child ill with cancer? Who is holding the local authority to account? Who is reporting the courts and challenging the decisions of judges or magistrates to withhold information? Who is fighting for the local community?

Local newspapers, whether in print or online, are on your side, and when they’re gone we’ll be left with a huge hole in the free speech society we value so much. But the stupid, annoying, enraging thing is, they don’t have to die. Yes, local newspapers are a business, and it’s one that’s struggling. This is, indeed, partly to do with the internet. The big traditional revenue streams for local papers, advertising of jobs, homes and cars, have had a massive hit as advertisers take their business online on their own websites rather than paying for pages and pages of print advertising.

There’s no doubt that newspaper groups are facing tough times. Last week Johnston Press chief executive Ashley Highfield said that the £300m loss the group – publishers of the Yorkshire Post and owners of the i newspaper – posted have been mitigated by a subsequent rise in advertising revenues. Trinity Mirror, however, which also owns national newspapers of course, posted operating profit of £25 million for last year. The NUJ has demanded answers from Newsquest boss Henry Faure Walker as to why its figures announced in February for 2015 – which showed a £47m loss – were at odds with the previous year’s £51 profit, given that the company had cut 3,500 staff from its books. Newsquest has apparently moved to a less-detailed accounting system which allows it to take “advantage of disclosure exemptions allowed under this standard”.

In other words, no one really knows how much the newspaper groups are actually losing or making. What is a fact is that the response to difficult times has been to cut journalism roles.

Last week the NUJ revealed that 400 journalism jobs have been lost in local newspapers in the last 17 months. That’s a lot of journalists from newspapers that are already run on shoestring resources. But the level of work hasn’t gone down – indeed, it’s increased as editorial staff are expected not only to get a paper out every day or every week, but also populate websites that strive for a 24/7 news ethic, and also use social media to promote their stories. Photographers have gone, sub editors are a dying breed, there are endless calls to utilise “user generated content” provided by readers who, really, just want to read the news, not to have to write it and illustrate it themselves.

It seems insanity to try to save money by chopping the resources that actually are the lifeblood of your business, but that’s what local newspaper groups are doing year in, year out. I have never met a more dedicated, hardworking and committed group of people than those I have had the privilege of working with on local newspapers since 1989, yet dwindling newsrooms are expected to provide the same level of service, and on notoriously poor wages.

It’s little wonder that very few of the student journalists I teach for a few hours a week want to get into local journalism. It’s no surprise that mistakes creep in. It’s perhaps no shock that the efforts of this last bastion of community are lampooned on social media for simply doing its best when everyone – the readers, the owners, the keyboard warriors who make snotty comments on online stories and seem to think journalism is something they’re entitled to get for free – seem to be doing their level best to put the boot in.

Just about 26 years to the day that I walked into my first newsroom, I walked out of my last one. Against the advice of a previous editor I’d taken a job with brackets in the title, and that left me exposed for the latest axe-swinging exercise. Don’t think this is a rant born of bitterness, though. It’s born of love. I shouldn’t imagine I’ll work in local newspapers again, but I have a fierce and boiling anger for the way they’re being ground into the dust.

I’d like to think that someone, somewhere is going to cast off the current striving for profit at any cost and that a progressive group of investors will one day wake up to the value of local newspapers and start pumping money into them and paying quality journalists what they’re worth. I’d like to think that. However… don’t hold the front page.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks