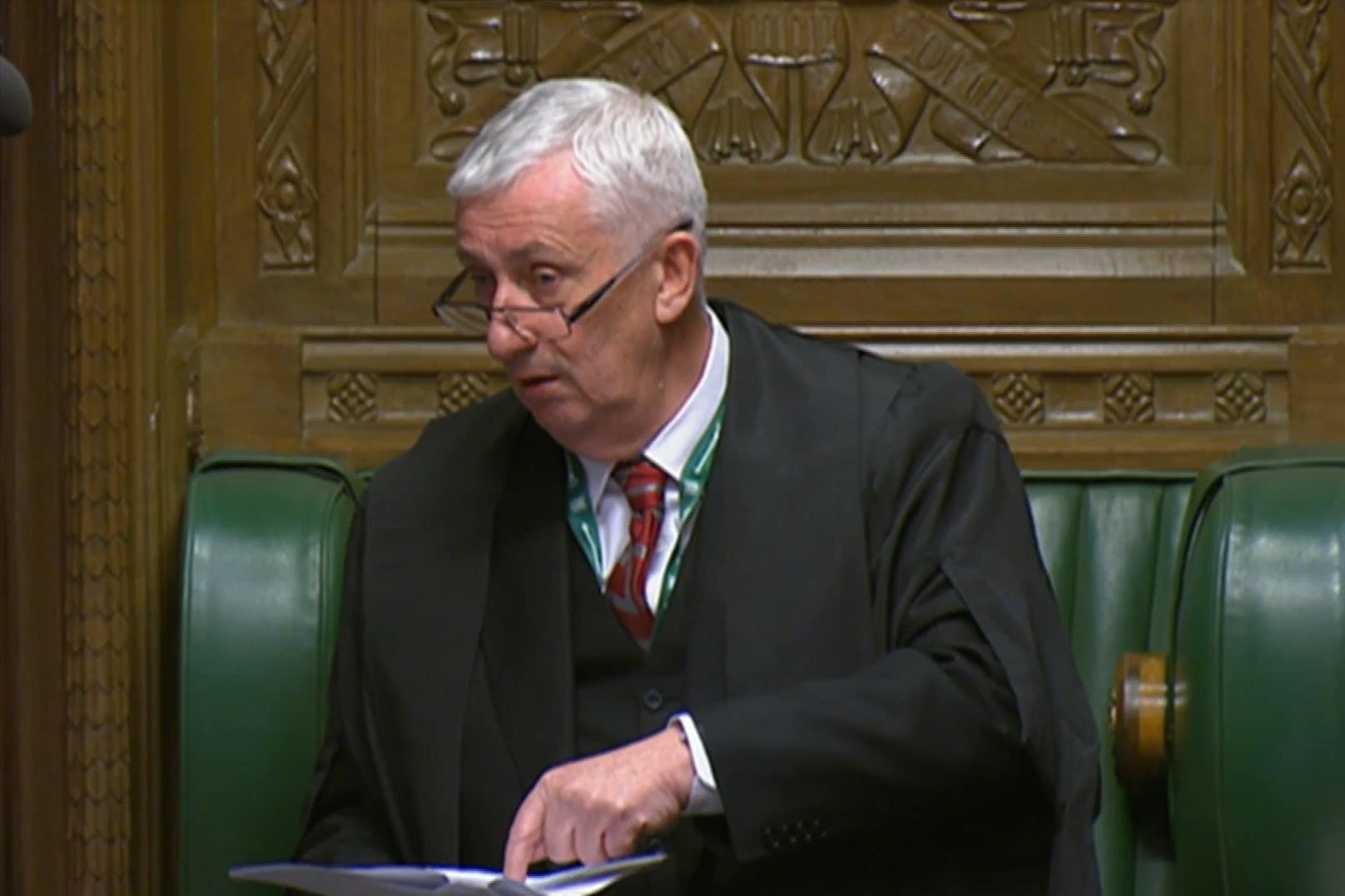

Speaker would have faced sack by Starmer if he had not caved in on Gaza debate

Sir Lindsay Hoyle tried to change the rules to help Labour avoid a split vote over a Gaza ceasefire but ended up pleading for his job, writes John Rentoul

While hostages languish in tunnels and another bit of Gaza is reduced to rubble, the British House of Commons did what it does best: played with words and argued about procedure.

Sir Lindsay Hoyle, the speaker, announced that all three main parties could have a vote on their form of words on the conflict between Israel and Hamas. There was uproar because this was a breach of convention. Indeed, the noisiest protests came when he said that the rules of the Commons were “outdated”.

Outdated? Scottish National Party and Conservative MPs were outraged. These were ancient rules, part of the birthright of freeborn Britons (including Scots) and a guarantee of our democratic freedoms. Or something. They date from, er, 1979.

That was when Norman St John-Stevas, the Conservative leader of the Commons and a great parliamentary reformer, changed the rules so that opposition parties could have a vote on their own motions.

Until then, the government was able to use its majority to wipe out opposition motions by amending them before they could be voted on. St John-Stevas changed the order of the votes so that MPs could vote on the opposition motion first, which would usually lose, and then vote on the government amendment – even though the motion it was amending no longer existed.

What Sir Lindsay did today was to restore the spirit of that enlightened reform: by allowing votes on all three parties’ policies on Gaza. The reason the SNP was so upset was that he spoiled its silly game of trying to embarrass Labour.

But then Sir Lindsay’s plan blew up in the most spectacular fashion. A “senior Labour source” told Nick Watt of the BBC that Labour had told the speaker that he wouldn’t keep his job under a Labour government if he didn’t change the rules.

This was furiously denied by Labour but it incensed the Tories. It was little more than a statement of the obvious: that the speaker would need the goodwill of the Labour Party if there were a Labour government. But for someone to say it out loud, and to a journalist, was asking for trouble.

The Tories were seething so much that Penny Mordaunt came to the despatch box to say that the government would withdraw its amendment and that its MPs would not take part in the votes.

This destroyed Sir Lindsay’s plan because it had the effect of denying the SNP the chance to vote on its own motion. With the Tories not taking part, the SNP motion was amended by Labour, wiping out all the SNP words and replacing them with Keir Starmer’s carefully crafted compromise wording about an “immediate ceasefire” with conditions.

The atmosphere in the chamber was rowdier and more passionate than at any time since the peak of the Brexit wrangles when John Bercow was speaker. Sir Lindsay sent Rosie Winterton, one of his deputies, to try to calm the House. But it would not be calmed. Stephen Flynn, the SNP leader in the Commons, raged: “Where is Mr Speaker?” He demanded that Sir Lindsay come to the House and defend himself.

Then most Tory MPs and the SNP walked out. William Wragg, the Tory MP, used a procedural device to force a delay.

When MPs came back, Winterton called the votes on Labour’s amendment and the motion as amended, which were both carried without a division – most of the MPs in the chamber were Labour MPs shouting “Aye”.

Once the votes had been held, a contrite Sir Lindsay took to the chair and pleaded for his job. He said he had tried to give all parties the chance to have a say on their policy on the Middle East, but “it ended up in the wrong place”. He apologised, “in particular to the SNP”, for the way things had turned out, and offered to meet “all the players” in private to try to learn lessons from the procedural chaos.

We shall see whether the Tory resentment against Sir Lindsay runs deep enough to get him sacked before the election. Flynn came as close as he dared to calling for him to go, but his fate lies in the hands of the Tory party and its parliamentary majority.

If Sir Lindsay survives, we can be sure of one thing: that he will be re-elected speaker if there is a Labour government.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments