Trigger warnings? Censorship? No! Bad attitudes in fiction need exposure and debate

I deliberately exposed myself to Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a work heavy on ableism. It was an unpleasant experience but I don’t want it censored, writes James Moore

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How does it feel to read something in which a fundamental part of you is being trashed?

There has lately been a fierce debate about the censorship and the application of trigger warnings to works of fiction using prejudicial words or displaying prejudicial attitudes to various groups.

The ableism warning slapped on to William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Globe is a recent example that has raised some people’s hackles. The character of Hermia, abused for her height, is played by Francesca Mills, who has a form of dwarfism. This prompted the warning.

I started thinking about this having picked up a volume of 1950s Western fiction displaying attitudes towards native Americans which today seem deeply regressive.

I abhor censorship. But it is difficult to offer informed comment on a debate unless you’ve properly lived it. Unless you’ve felt the literary abuse up close and personal.

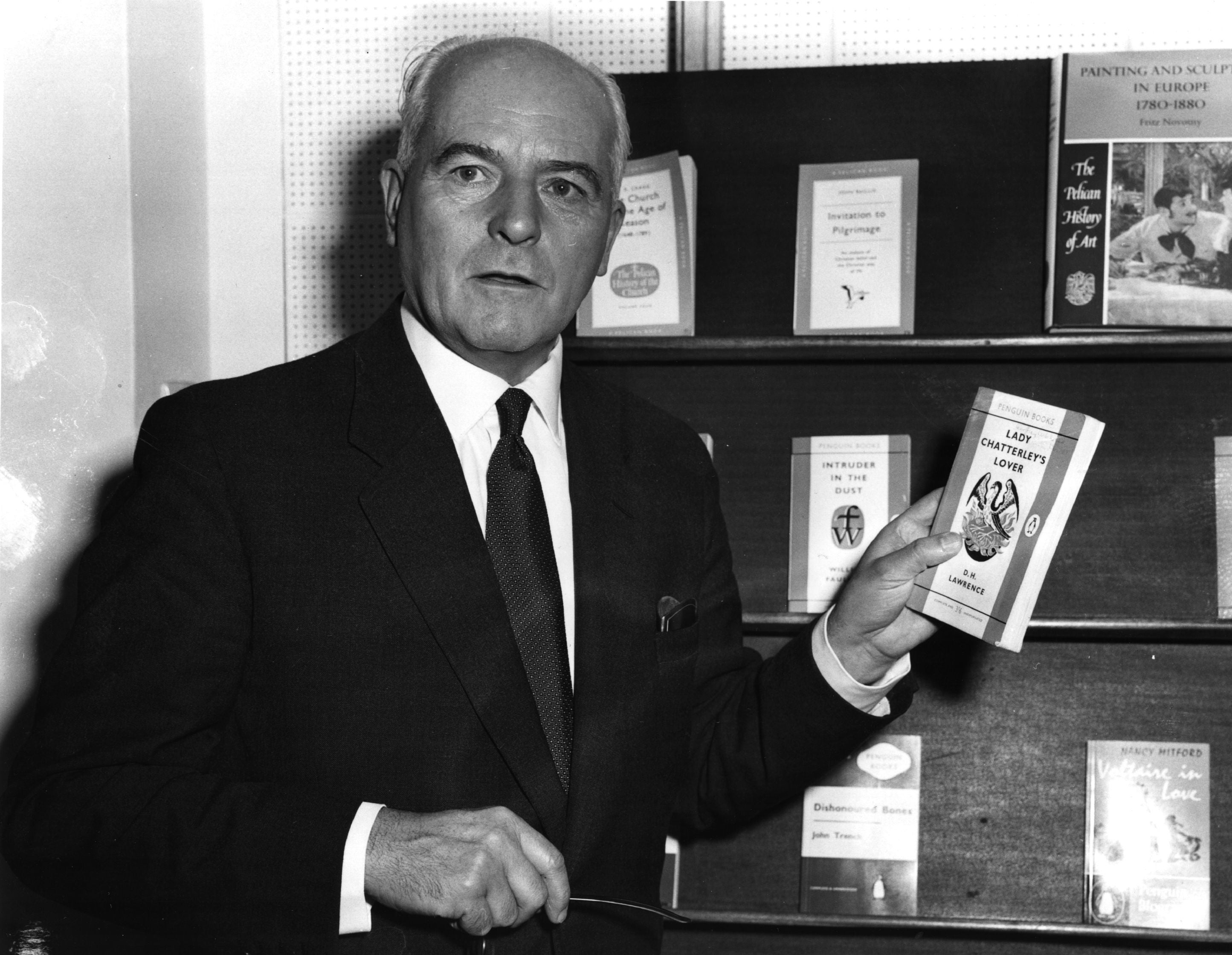

So, disabled as I am, I downloaded Lady Chatterley’s Lover, one of those famous books that is much more often talked about than read. Perhaps because it’s a bit of a slog?

The book’s ableism becomes evident far more quickly than the passages it is best known for, the ones which led to the infamous obscenity trial featuring that dreadful rhetorical question about whether the novel was something “you would even wish your wife or servants to read”.

But how about your disabled relative? That question wasn’t considered then. Perhaps it should have been.

Sir Clifford Chatterley is described as coming back from the war “broken”. He was, we are told, “shipped home smashed”. His use of a motorised chair to get about his estate is rather lampooned. Oliver Mellors, the virile gamekeeper, has to help when it gets stuck in the mud.

The combination of Sir Clifford’s paralysis and impotence is an important theme, a means of skewering an ineffective, callous and outdated aristocracy.

And yes, reading it was quite upsetting. I did not suffer a spinal chord injury when my own body was, to quote Lawrence, “smashed”. But I had breaks in my spine and in almost every other bone, not to mention lingering nerve damage, chronic pain and other problems to add to a pre-existing autoimmune condition (type 1 diabetes). So my body was indeed, as you might say, smashed.

Broken too? I’m tempted to indulge in some robust Anglo-Saxon there. I was left blooded – quite literally (I have the scars) – but unbowed.

The unpleasant ableism contained within the book has been under-discussed. It is not even mentioned in the Wikipedia page. I didn’t see much about it accompanying the recent, supposedly evolved, Netflix film adaptation either. Which is disappointing.

As someone who has been abused on the street for my condition, I want it discussed. I want people to see it and understand what Lawrence was doing, and then to debate the way Lawrence explores and exploits disability.

It is a very ugly part of the work (and its adaptations). Some historical context is due: Most of those left with long-term injuries after the First World War weren’t aristocrats of any kind. The fact that the society they returned to mocked and demeaned them for being “crippled”, “broken”, and “smashed” is shameful.

In an essay for Book Riot, Grace Lapointe says: “As a disabled woman, I’ll never consider it feminist. A female, non-disabled character’s sexual liberation shouldn’t be at the expense of disparaging a disabled, male character.”

Quite so. But should we then censor it or change it? No. To the contrary. I would prefer for people to read it and think about it. It’s ableism has been all but absent from the discussion about the book and that’s a problem because ableism, society’s bad attitudes towards disabled people, is too rarely debated. And we need to debate and show it up for what it is.

If we alter works from earlier epochs – something that is sometimes suggested today – because they are offensive I would argue that we do a disservice to the groups on the receiving end.

Glossing over the bad attitudes of the past to coddle today’s overly sensitive readers? No. That stuff existed. Those attitudes existed. Hell, they exist today.

The ableism directed against Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream? It too needs to be discussed. But the trigger warning? Questionable. It arguably does a disservice to Mills, who is doing something powerful, bringing something to life, making an audience think.

It would surely deliver a more powerful and visceral experience if they were able to see Hermia demeaned by Lysander as a “dwarf”, “bead” and “acorn”, and then bullied by Helena before she fights back, without knowing it’s coming.

Ableism is shocking. It’s horrible. In the last month, I’ve experienced it on multiple occasions, been abused simply for taking to a local park to exercise (a matter of metres from the constituency office of our local MP, Labour frontbencher Wes Streeting).

The attitudes in the book, and in the play, they haven’t gone anywhere. You may recall that Shakespeare also used disability to other his eponymous villain in Richard III too. The self-hating title character describes himself as “rudely stamped”, “curtailed of this fair proportion”, “cheated of feature” and “deformed, unfinished”.

Disability is frequently associated with defects of character, even wickedness. It wasn’t that long ago that the former England manager Glen Hoddle strayed into that territory in a controversial interview with The Times, in which he claimed disabled people were being punished for sins in a previous life, which ultimately led to him losing his job (he later apologised).

Richard is also, arguably, one of the earliest examples of the reductive “scarred villain” trope particularly prevalent in the Bond film series (to its credit, the British Film Institute has rightly decided it will no longer fund films which rely on this cheap, lazy and nasty stereotype).

But that doesn’t mean the play shouldn’t be staged. It should be. And then it should be discussed.

If you have a disability you will see the attitudes it depicts up close and personal. Their existence shouldn’t be glossed over. Better to show them up for what they are.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments