Don’t believe the hype about a new Labour rebellion. Centrism is dead

In Britain, and in Europe, the centre governed with the grudging acquiescence of trade union leaders – but no longer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Headlines say that Jeremy Corbyn’s centrist opponents are, yet again, preparing for a takeover. They are wasting their time.

The centre-ground has been dwindling for years, under the impact of austerity and wage stagnation. This is why they haven’t been able to take over despite three years of sabotage, and why they daren’t split. This isn’t 1981.

In 1981, David Steel told delegates of the Social Democratic Party, a centrist breakaway from Labour, to “go back to your constituencies and prepare for government”. This looks vainglorious in retrospect, but it had a basis. There was a backlash among middle class liberals, hitherto part of the Labourist coalition, against the trade unions and the hard left. Many trade union “moderates” were keen to break the cycle of militancy beginning with the strikes by seamen and women Ford workers in the late Sixties.

Pollsters spoke of realignment, the end of class voting. Labour’s policy instruments were discredited. Years of brutal wage cuts organised through a deal with the unions, led to demoralisation and a turn to the right. The Liberals and the SDP sought to build a new centre, free of allegiance to business or labour, able to govern in the “national interest” – which meant recuperating what remained of the postwar consensus.

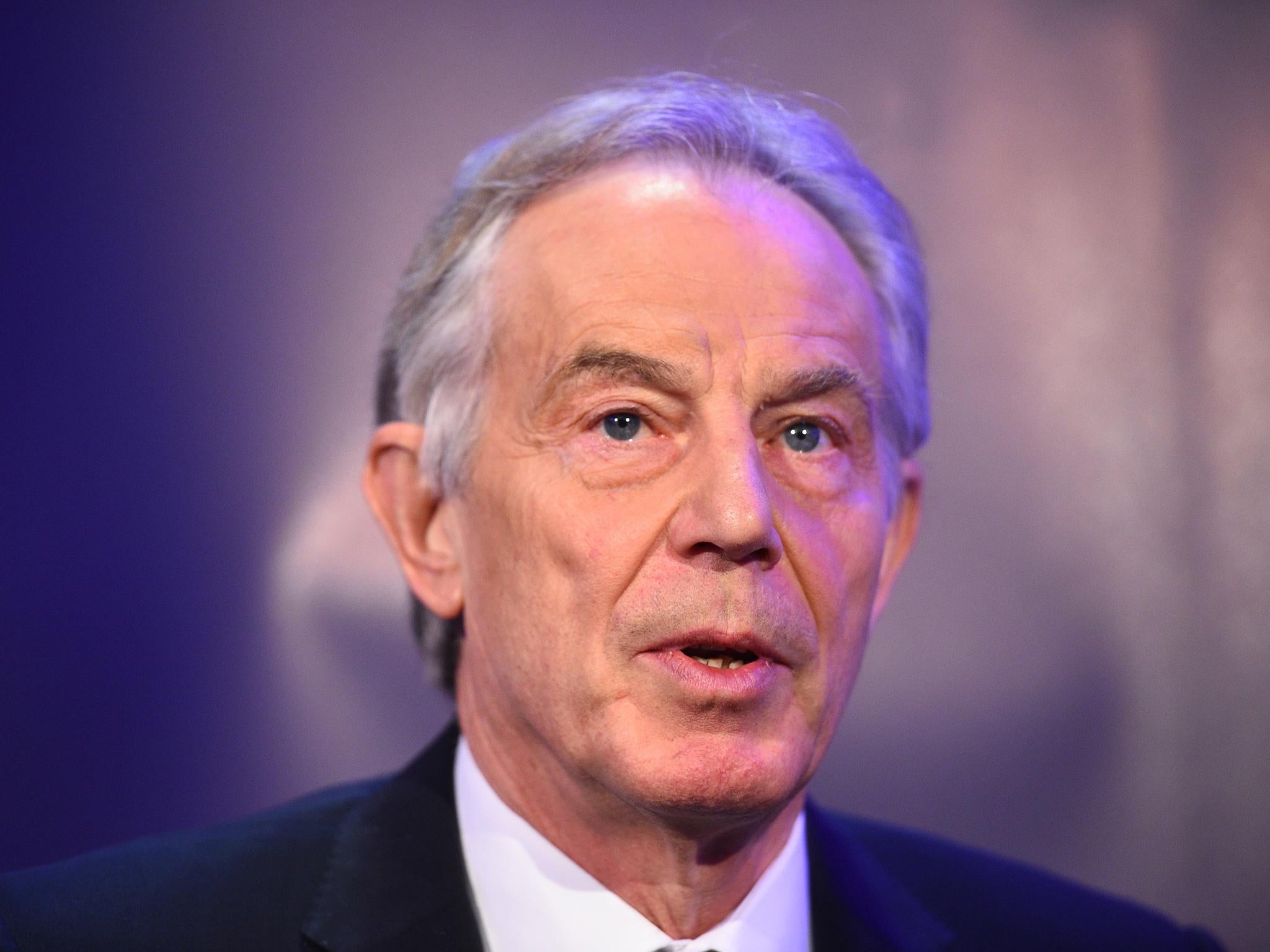

In the short run, this failed. It only consolidated an electoral split, handing stupendous majorities to Margaret Thatcher. But in the long run, the violent crushing of unions and epochal political defeat of the left created the space for a new centre to emerge under Tony Blair. As long as the global economy was expanding, powered by huge growth in south-east Asia and the explosion of the financial sector, there was enough political stability to support the post-Thatcher consensus. And it didn’t matter if voting turnout collapsed among poorer voters, since a few “swing voters” would anchor government to the centre.

Nor was this just the state of affairs in Britain. The consensus was consolidated in the United States under Clinton, in France under Jospin and Chirac, and in Germany under Schroeder, and was institutionalised in transnational arrangements, from the World Trade Organisation to the EU Constitutional Treaty.

The global crash did not immediately change this. Surreally, the main electoral reflex from the worst crisis of capitalism since the 1930s was the “Cleggasm”.

Less surreal was Obama’s victory in the United States and Hollande’s success in France. In the face of uncertainty, people wanted reassurance: the political centre was a security blanket.

But since approximately 2014, the centre has been in freefall in Europe and North America. In Spain, the PSOE leadership went into crisis. In France, Hollande was reduced to 6 per cent of the vote. In the UK, the Liberals collapsed, and the left took the leadership of the Labour Party. In the US, Trump won. The one exception, Macron, styled himself as an outsider, but is less popular than Trump now.

What happened? Political scientist Thomas Ferguson tried to answer this question by studying how Trump won in America. Ferguson is best known for his “investment theory of politics”, which says that politics costs more than classical democratic theorists realised.

Thus, electoral systems tend to be monopolised by well-funded investor blocs seeking to legitimise their interests. Had the 2016 presidential election been between Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton, Ferguson says, it would have reflected this. But this only works if voters accept it as legitimate. Already in 2014, Ferguson and colleagues predicted an electoral rupture, as unprecedented turnout collapse showed the legitimacy of the system was collapsing.

In Britain, and in Europe, investor competition is complicated by mass trade union movements linked to social democratic parties. The centre governed with the grudging acquiescence of trade union leaders – until recently.

As long as the system was delivering growth, weakened unions were tactically conservative, resisting major offensives for fear of losing more. However, the crisis of the unions has only worsened in recent years of relative economic stagnation and austerity. The union leadership’s despairing break with the centre helped give Corbyn the leadership.

The problem for today’s centrists is that the consensus which made them the centre disappeared, and it isn’t coming back. Until they come up with a new agenda, they’re claiming territory that no longer exists. So what are they in the centre of?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments