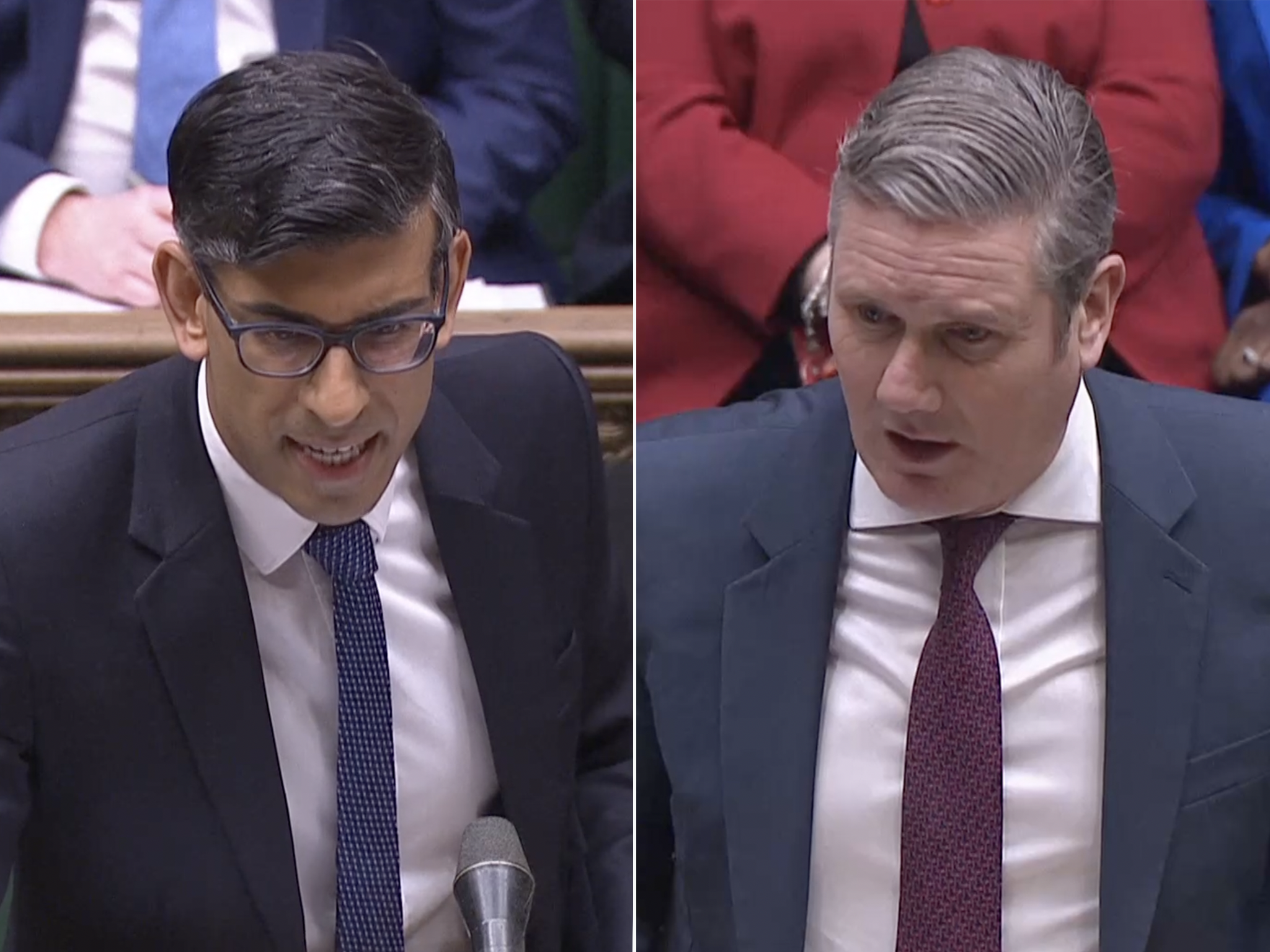

No, they’re not ‘all the same’: the gap between Labour and the Tories is real

Even after Keir Starmer’s forced march to the centre, there is still a big difference between the parties, argues John Rentoul

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are few policy differences between the Conservatives and the Labour Party, as has been pointed out approvingly by me and disapprovingly by others. A government led by Keir Starmer would spend a bit more on the NHS and schools, paid for by taxing non-doms and private schools a bit more.

There are other possible differences that are unclear, or that will have been overtaken by events by the time of the election. Labour would extend help with gas and electricity bills, paid for by raising a bit more from the windfall tax on oil and gas companies, but Jeremy Hunt will probably do something similar in the Budget next month.

Labour also currently intends to borrow large additional sums to pay for a Green Prosperity Plan, but I think Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, will tweak that policy so that it meets Hunt’s new rule against borrowing more than 3 per cent of national income in a year. Starmer endorsed Gordon Brown’s plan to replace the House of Lords with an Assembly of the Nations and Regions, but neither he nor Brown said how its members would be chosen.

Which puts Starmer in a similar position to that of Tony Blair between 1994 and 1997. Some readers would rather I never mentioned Blair again, but whether you are for him or against him, I don’t think you can understand politics now without understanding politics then.

Every policy change Blair made as leader of the opposition brought Labour closer to the position of the Conservatives. He promised to spend a bit more to achieve modest targets for public services, paid for by, among other things, a windfall tax on the privatised utilities. And he had a big programme of constitutional change: devolution for Scotland, Wales and London; the expulsion of the hereditary peers from parliament; freedom of information law; and the Human Rights Act.

But on the central questions of taxing and spending, the gap between the parties’ prospectuses in 1997 was trivially small. So it will be again in 2024. Yet that does not mean that “they’re all the same”, a common complaint of the averagely engaged voter. It does not mean that Starmer is just a Tory with a different colour rosette, or that it will make no difference whether there is a Labour government or a Tory one after the next election.

We have only to consider the 13 years of the last Labour government to know why. Although that government bound itself to Conservative spending plans for its first two years, in an unusual attempt to reassure voters that it was not going to wreck the public finances, it did then increase spending on the NHS, schools and other public services. So much so that we now look back on 2010 as the end of a golden age.

If there had been no Labour government over that period, public spending would probably have increased – but not as much, as more of the dividend of growth would have been returned to taxpayers in tax cuts.

Given how badly the Tories lost in 1997, it is a counterfactual that is hard to imagine, but it underlines an essential truth of the next election. Which is that a Labour government would devote more of the proceeds of growth to spending on public services, whereas a Conservative government would devote more to tax cuts.

Rishi Sunak appeared to be a Blairite pragmatist when he put taxes up to pay for the coronavirus and the global energy price shock, but he would be trapped by the demands of his own party for tax cuts even if he didn’t believe in them himself. Even if he hadn’t called himself a Thatcherite, and even if he didn’t have Liz Truss and her supporters insisting she was right in the face of the evidence, any Conservative government would be likely to cut taxes and reduce public spending more than any Labour government.

Truss, in her failed premiership and her quixotic attempt to justify it, is merely an extreme manifestation of the Conservative cast of mind. Her arguments don’t make sense, but they express an authentic Tory instinct against the overmighty state.

One of her targets is the Office for Budget Responsibility, set up by George “Austerity” Osborne, which she says has too much power. Apparently, this power consists of the ability to point out that her sums didn’t add up – as if, without the OBR, they would have done. Does she really think that, if there had been no OBR, the markets wouldn’t have noticed that Kwasi Kwarteng’s plans were for government borrowing to continue to rise indefinitely?

The big fiscal decisions are only the most important of the thousands of decisions ministers make every day. In a Labour government they would tend in one direction; in a Conservative one, another.

Take one less-obvious example: rough sleeping. It can never be eliminated completely, but under the last Labour government it was reduced to a minimum. Since then it has gone back up, except for two weeks in March 2020 when the pandemic prompted the authorities to clear the streets. It doesn’t take much public spending to solve rough sleeping, but it does take some, and it takes political will, which was fitful under the Tories and focused under Labour.

So that is why I think the choice at the next election, or at any election, matters. It does make a difference, especially over time. The manifestos of the two main parties may look the same, but their hearts are in different places.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments