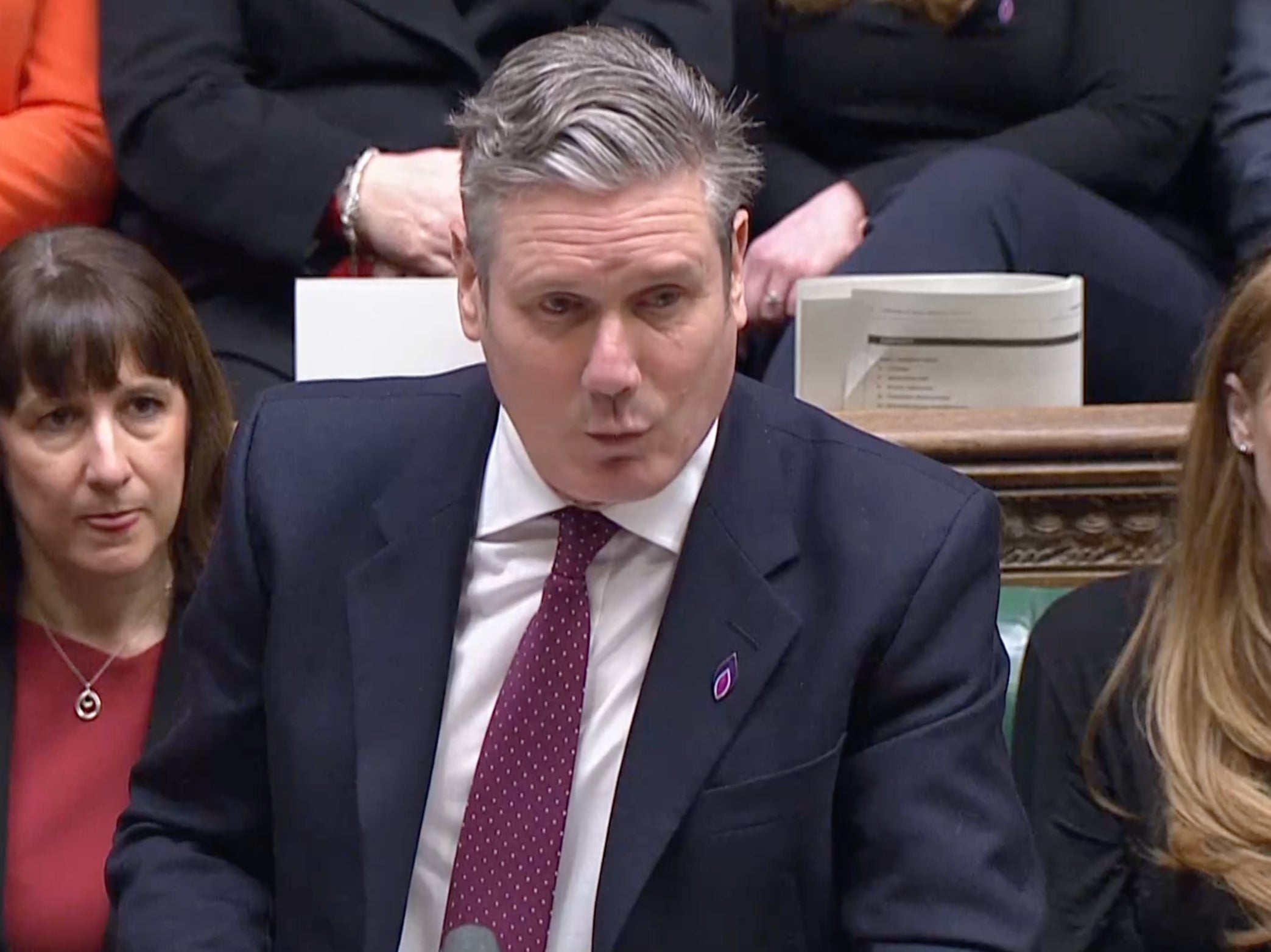

Keir Starmer failed to make the case for Nadhim Zahawi’s resignation

The Labour leader tried too hard, allowing the prime minister to hold the high moral ground of due process, writes John Rentoul

Not for the first time, Westminster was agog. Speculation about when a minister would resign dominated journalists’ conversations before Prime Minister’s Questions. Would Nadhim Zahawi, the Conservative Party chair, be sacked after the Today programme? Mid-morning? Five minutes before PMQs? Or by Rishi Sunak in his first answer?

Not for the first time, the clash between prime minister and leader of the opposition was an anti-climax. Keir Starmer realised that people outside the Commons were less interested in the processology of a minister whose career is hanging by a thread, and so he devoted his first three questions to the failure of the probation service in releasing the violent criminal who murdered Zara Aleena.

The prime minister couldn’t say much except how sorry he was, and that the government was doing what it could to improve training, hire more senior probation officers and spend more money on the service.

He didn’t respond to Starmer’s indirect charge that he had “blood on his hands”. The Labour leader quoted Aleena’s parents using the phrase, but it would have been better if he hadn’t. Such emotive language should have no place in politics: bad things will happen; not all criminals will be caught or forestalled, even if in hindsight there were things that the authorities could or should have done.

To suggest that ministers are personally responsible for deaths in such cases helps no one. Terrible things will happen under a Labour government, even if it is better run than the current one; Starmer may find those kinds of words used against him one day.

It would have been better if Starmer had stayed off the subject of Zahawi altogether. There are plenty of subjects that matter to voters more. The Labour leader had one of his most effective quarter-hours in the Commons last week when he devoted all six questions to ambulances. He could have asked about them again, or he could have asked how the plan was going to block-book social care beds to give hospitals somewhere to discharge patients.

Instead, Starmer leadenly switched to the obvious subject for his second set of three questions.

He asked what should happen to ministers “seeking to avoid taxes”. It is not much of a question. Avoiding taxes is legal. Anyone who opens an ISA is avoiding taxes. Evading taxes is quite different, but he cannot accuse Zahawi of doing that, because he doesn’t know that Zahawi was deliberately trying to pay less tax than the law required.

The prime minister explained that he had appointed an independent adviser on ministerial standards – as the opposition had urged him to do – and that he had referred the Zahawi tangle to him. Sunak pointed out that Starmer read out question five “from his prepared sheets” without listening to his previous answer, which was true, and explained that he wasn’t going to decide a cabinet minister’s fate just to suit the parliamentary timetable of PMQs at noon. He was going to follow due process. Starmer, barrister and former head of the Crown Prosecution Service, had nothing to say about that.

Instead, Starmer went for low politics. He said: “We all know why the prime minister was reluctant to ask his party chair questions about family finances and tax avoidance.” A low, but legitimate, reference to the prime minister’s wife’s non-dom status.

Starmer’s final shot was to ask: “Is he starting to wonder if this job is just too big for him?” I assume this was a deliberate reference to Sunak’s height – if not, it was insensitive, but if so it was a disgrace.

Politics ought to be better than that. Starmer had come to the Commons knowing that expectations were high that he would “deliver the knock-out blow”, “put the ball in the back of the net” and all those other tedious analogies.

But he knew too that he had no new information, no unanswerable questions about Zahawi’s tax affairs, because no one – not even Dan Neidle, the retired tax accountant who probably forced Zahawi to settle with HMRC – can contradict Zahawi’s assertion that he made a “careless, not deliberate”, mistake.

So Starmer tried too hard, allowing the prime minister to hold the high moral ground of due process, while he, who aspires to be prime minister himself, waded into the swamp of personal abuse.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments