Justice demands court records are kept

The more that we can preserve of the workings of our judicial system, the more we will know about our society

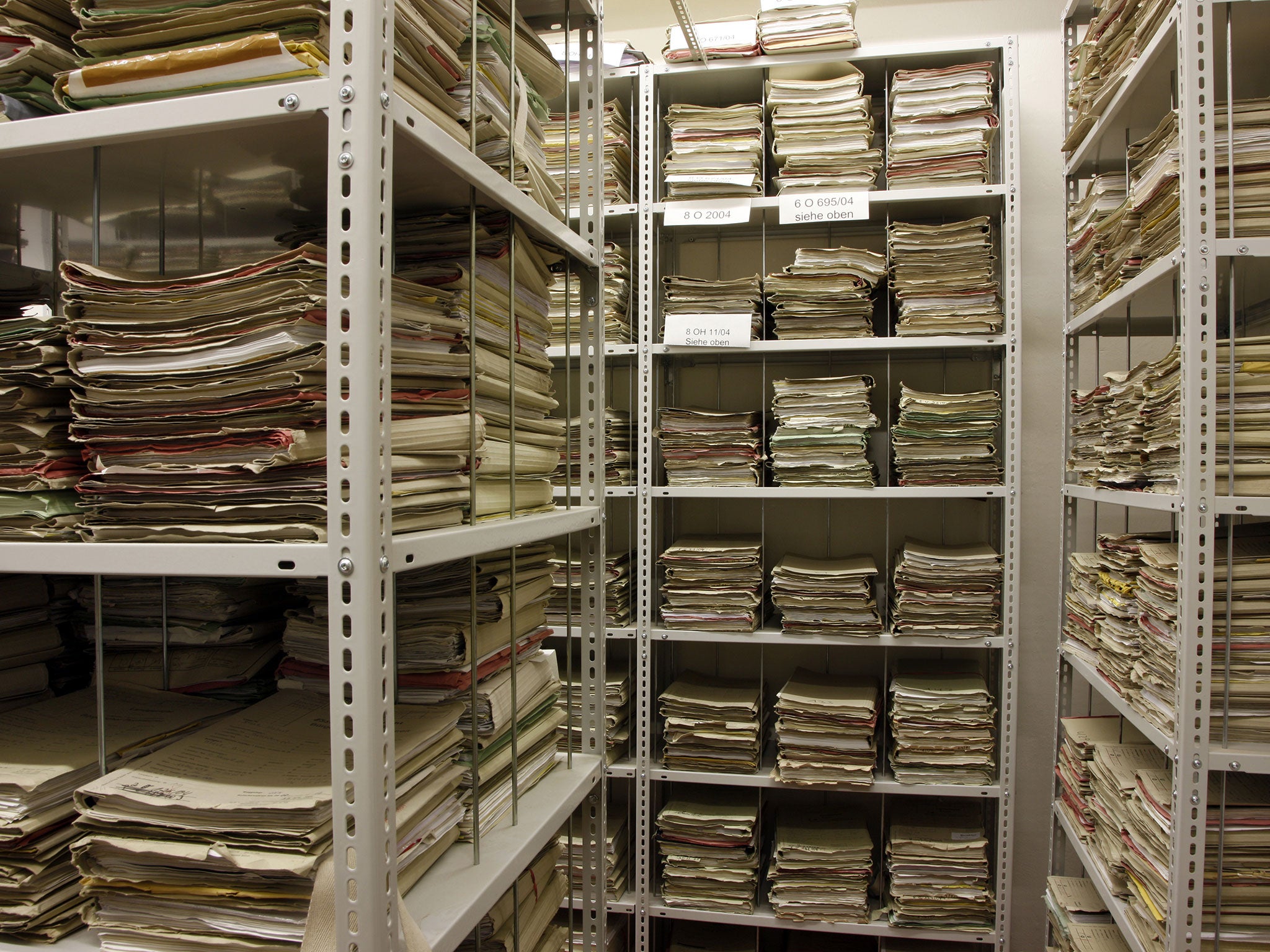

Open and accountable justice requires records to be kept. Those who believe they are the victim of a miscarriage of justice need to know what was said at their trial if they are to show that they have been wrongly convicted. It seems extraordinary, therefore, that official guidelines require the destruction of the recordings of court cases after seven years.

This is not new news, yet we report it today because we believe it to be an important failing in our legal system. Actually, we are reporting the demands being made of Michael Gove, the Secretary of State for Justice, by leading appeal lawyers to order the indefinite retention of court recordings.

The campaign to retain recordings hopes to exploit public awareness of the difference between our legal system and that of the United States, which has been highlighted by the popular online documentary, Making a Murderer. It shows defence lawyers using court records from 2005 to try to overturn the conviction of Steven Avery. In many states in America, people who are convicted are automatically given a recording or transcript of their court proceedings. In this country, there is no guarantee that someone launching an appeal so long after their conviction could obtain such records.

Most Crown Court hearings are recorded in full, but Ministry of Justice guidelines say these recordings should be deleted after five years for tape-recordings and after seven years for digital recordings. Since 2011, most court recordings are made digitally. There are exceptions. In terrorist cases and some drugs cases, recordings will be held for longer, or the judge can order the recordings be preserved. In some cases, it may be possible after more than seven years to obtain a transcript from a court services company, but these are also often destroyed, and if they have been kept can be expensive. Some companies charge thousands of pounds for transcripts of, say, a three-week case.

Obtaining justice for those wrongly convicted should not be a lottery, however. Many cases of innocent people locked up for crimes they did not commit have relied on arbitrary and fragmented records pieced together sometimes decades later. There is no good reason, and certainly no good reason with today’s technology, when most people store more than a year’s worth of books and audio-visual data on their smartphones, not to retain all court recordings and transcripts indefinitely. We suspect that the reason for the Ministry of Justice’s guidelines is a combination of inertia, from the days when the storage of audio tape quickly came up against physical limits, and of institutional bias against making it easy to appeal. Our congested criminal justice system does not want to encourage a heavier publicly funded caseload.

Mr Gove does not want to put obstacles in the way of reversing miscarriages of justice, we are sure. We have praised him before for showing welcome signs of a liberal conscience in his new post, in sharp contrast to Chris Grayling, his predecessor. So we are confident that he will want to review his department’s guidelines.

This is not simply a matter of justice, but of history. The more that we can preserve of the workings of our judicial system, the more we will know about our society, and the more our descendants will be able to know.

But the argument is primarily one of justice. One of the founding principles of British justice is that its deliberations take place in public. That accountability is only meaningful, however, if records are kept so that everyone can refer to what was decided and why. Mr Gove could earn a lasting place in history if he were to ensure that court recordings and transcripts are available at reasonable cost and kept in perpetuity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks