Junior doctors have been treated with contempt by Jeremy Hunt – forcing their hand will damage the NHS

The Health Secretary will have to take a good deal of the blame when the pace of junior doctor emigration picks up

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ending “uncertainty” is, according to Jeremy Hunt, the ambition. The Health Secretary announced on Thursday that there would be no more negotiations with junior doctors, and that on 1 August the Government will impose a contract upon them, leaving 55,000 staff working under terms to which they did not sign up, and have not agreed. That is likely to destabilise the NHS, rather than secure its future.

The frustration of the Government is not entirely unreasonable. Its final offer gave some ground in important areas: it announced that fines would be imposed on trusts that over-worked doctors – a crucial backstop that had been undermined in the initial contract proposals; it offered increased weekend pay for those junior doctors who work one in four Saturdays or more. And medics working extra-long hours would have been given a corresponding bump in salary.

Questions remain over the entire project of the seven-day NHS. The threat to citizens of a five-day service was irresponsibly exaggerated. It is only elective procedures that will now be available on weekends; emergency care always has been. And yet, the final contract offer of Jeremy Hunt cannot accurately be described as insulting. The BMA’s response – asking that every Saturday be paid at an “out-of-hours” rate, in return for a substantial cut in the basic pay increase of 11 per cent – shows that pecuniary concerns do not lie at the forefront of the union’s thinking. But it does reveal a certain unwillingness to treat weekends as workdays, which must count as a stumbling block towards a negotiated settlement ever being reached.

The public broadly supports the junior doctors in their strike, with 60 per cent still in favour even as the second day went ahead. But the Conservative Party argues that the population also supports a seven-day NHS, and showed as much by voting them in, with that measure in their manifesto. Those who believe it vital for junior doctors to go another extra mile and work weekends will probably still favour the Government’s stance. Those who put staff satisfaction above that project will back the doctors.

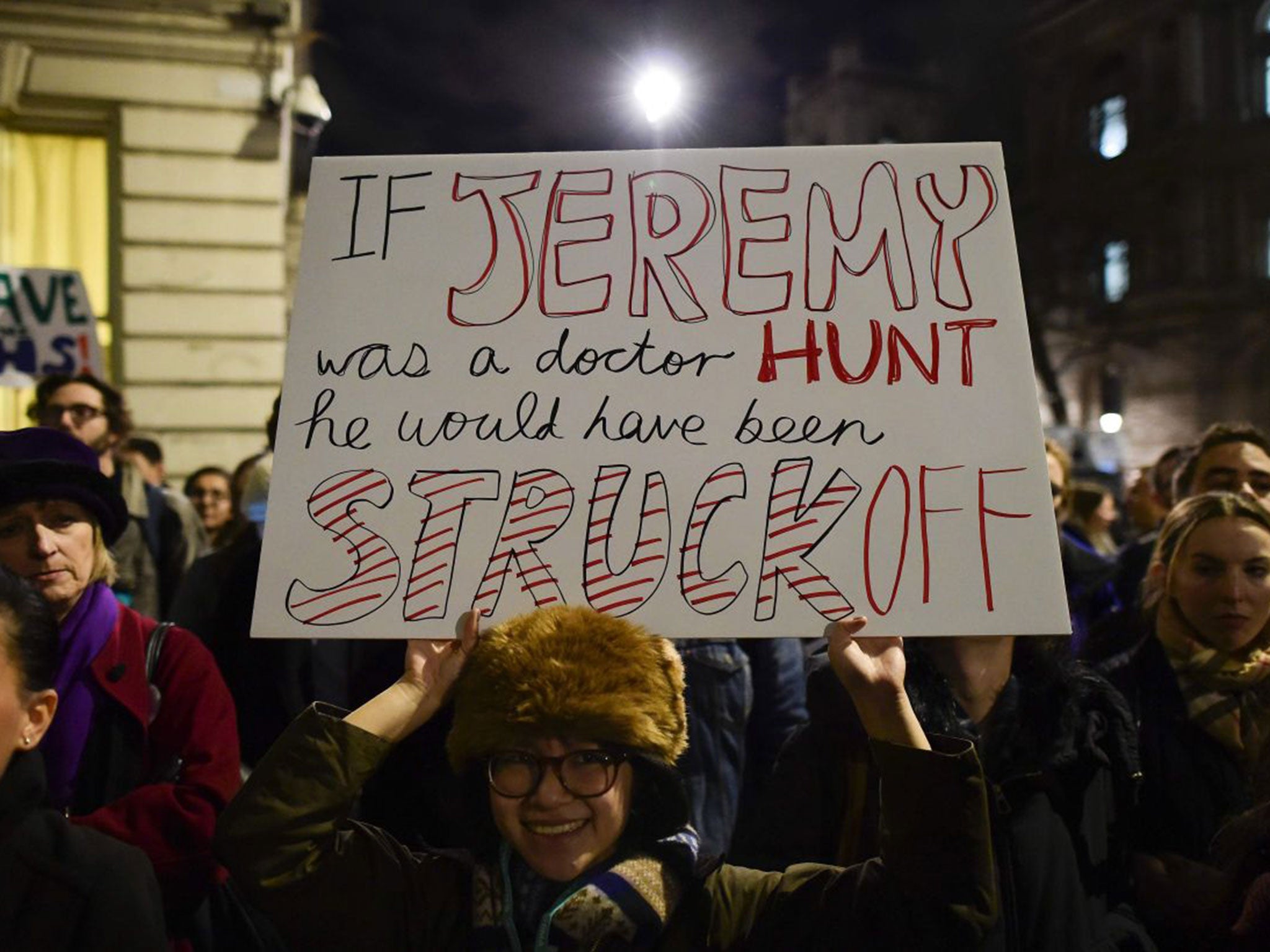

This newspaper falls into the latter camp. And, whatever the subtleties of the most recent negotiation, the Government holds great responsibility for letting the dispute develop to its current pitch of acrimony. Mr Hunt has behaved disrespectfully almost throughout. He has treated one of the most productive and diligent elements of the British workforce as truculent and greedy. He has dismissed legitimate concerns as union tub-thumping. The final straw will, for many, be the imposition of this contract, and Mr Hunt – or, more likely, his successors – will be left to reap the consequences.

What is now certain is that more junior doctors will leave the NHS, and fewer sign up to it. The Independent reported on a survey showing 90 per cent would consider moving abroad were the contract to be imposed upon them. One in three GP trainee positions is already unfilled. The loss of a portion of the base of the NHS pyramid (junior doctors make up a third of the entire staff) could hardly come at a worse time, as demand for the service increases, and annual funding bumps fall 3 per cent behind this yearly rise.

That shortfall cannot be blamed on the Conservative Party alone. The public appears unwilling to contemplate paying more for the NHS, through an increase of 1 per cent in national insurance, say. But responsibility for turning a contractual dispute into a pitched battle lies with Mr Hunt, and he will have to take a good deal of the blame when the pace of junior doctor emigration picks up. His legacy will be a weakened, overstretched NHS.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments