John Roberts apparently doesn’t understand what the Supreme Court is

‘You don’t want the political branches telling you what the law is, and you don’t want public opinion to be the guide,’ Roberts said. That reveals a deep misunderstanding of what his job is supposed to be

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Supreme Court justices are political actors, and as such, they sometimes try to justify themselves to the public. They often do this, ironically, by insisting that they have no need or responsibility to justify themselves to the public.

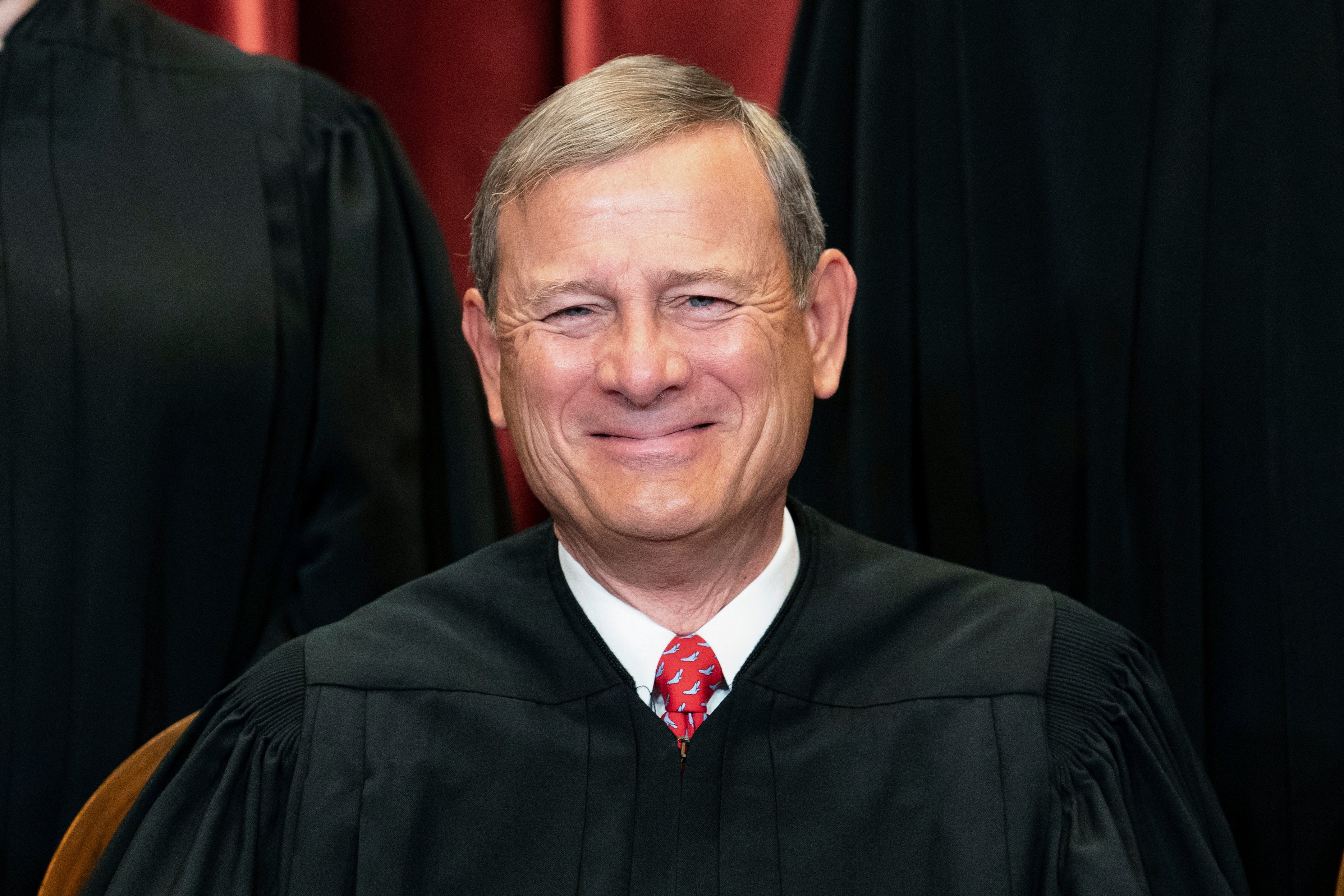

Chief Justice John Roberts unfurled this self-refuting argument once again over the weekend. He did so in a somewhat more strident register than usual, as the Court’s approval has plummeted to a ludicrous historical low of 25 percent.

“If the court doesn’t retain its legitimate function of interpreting the Constitution, I’m not sure who would take up that mantle,” Roberts said in his first public comments since the Supreme Court gutted abortion rights. “You don’t want the political branches telling you what the law is, and you don’t want public opinion to be the guide about what the appropriate decision is.”

There are a number of reasons to be skeptical of Roberts’ sweeping demand for absolute, unquestioned authority over the law and the Constitution.

In the first place, many questions about the court’s legitimacy have little to do with public opinion.

Reporters keep uncovering more and more evidence that the actions of Ginni Thomas have badly compromised her husband, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Ginni lobbied numerous officials in an effort to get them to illegitimately and illegally overthrow Joe Biden’s 2020 election victory. She also has extensive connections to anti-abortion groups who were working to persuade the Supreme Court to overthrow Roe v Wade.

In an honorable, legitimate court, justices with these kinds of familial connections recuse themselves when relevant. Clarence Thomas should not rule on cases involving the 2020 election, Donald Trump, abortion rights, or any other issue involving his wife’s extensive far-right advocacy. But Thomas has never recused himself from cases linked to his wife. Observers can reasonably conclude that the court is not impartial; that it is instead an illegitimate refuge of corruption and partisan hackery.

More broadly, the Supreme Court is appointed by presidents chosen by the electoral college and by the Senate which approves those appointees. But both electoral college and Senate elections are strongly biased in favor of white, rural Republican voters. As a result, the Supreme Court has a 6-3 Republican supermajority, even though Republican presidents have won the popular vote only once in the last 30 years. In 2000, a conservative Supreme Court interfered in a close election and chose a Republican president to perpetuate the court’s own preferred right-wing hegemony.

Again, court-watchers have good cause to look at the unrepresentative court and conclude that it is a partisan institution committed to undermining popular will and subjugating the public to its minoritarian policy preferences.

Roberts’s response is that the popular will and policy preferences are irrelevant, and that you don’t want public opinion or “the political branches telling you what the law is.” This is incredibly arrogant. It’s also false.

Obviously, the Founders intended the political branches to tell you what the law is. The power to make law is literally vested in Congress, a political institution. The power to enforce the law is vested in the executive branch, a political institution. The entire point of the democratic system is that democratic political institutions make the law, based in no small part on the preferences of the public, which elects them.

More, the court is itself a democratic institution, subject to politics. Its members are chosen by the political branches. And they are subject to ongoing checks which are supposed to make them accountable to Congress, the executive, and the public.

Congress has the power to impeach justices who engage in flagrant ethical violations — as Clarence Thomas has. The president and Congress can also adjust the make-up of the court by adding justices. This is what Franklin D. Roosevelt threatened during his second term, when a reactionary Supreme Court blocked all legislative efforts to address the Great Depression.

The court-packing controversy is often remembered as a defeat for Roosevelt, because he did not actually add justices. But the political battle led the court to become much less obstructionist; it began to rule in favor of Roosevelt’s legislative agenda. FDR was elected twice more. The court acquiesced to public support for him.

In FDR’s time, public opinion and political institutions shaped the law. That’s not a sign of democratic failure. It’s an example of democracy working.

The Supreme Court is an institution in a democratic country. It draws its legitimacy from democracy and popular government. It is supposed to be subject to democratic checks and balances. When it dispenses with precedent to strip more than 150 million people of basic bodily autonomy, there’s every reason for those targeted to declare the court illegitimate.

If we are to take Roberts’ words seriously, then we would have to conclude the court should never be questioned. If the court abolishes democratic elections (a real possibility) or decides that disenfranchising Black people is legal (again, not really a hypothetical), then that’s the law. Congress, the president, and the public just need to nod and smile and march into the authoritarian future in smiling lockstep, maybe muttering a quiet “thank you” as their judicial overlords kick them in the rear.

But, of course, that is not in fact democracy. We did not get rid of a king just to install a bunch of robed monarchs. If the court is not subject to democracy, then it is tyranny. And the United States was founded on the principle that tyranny is illegitimate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments