Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We live not so much in the age of the robots as in the age of worrying about the robots.

New books and think pieces proliferate about the threat to the world’s workers from the twin forces of digitisation and automation.

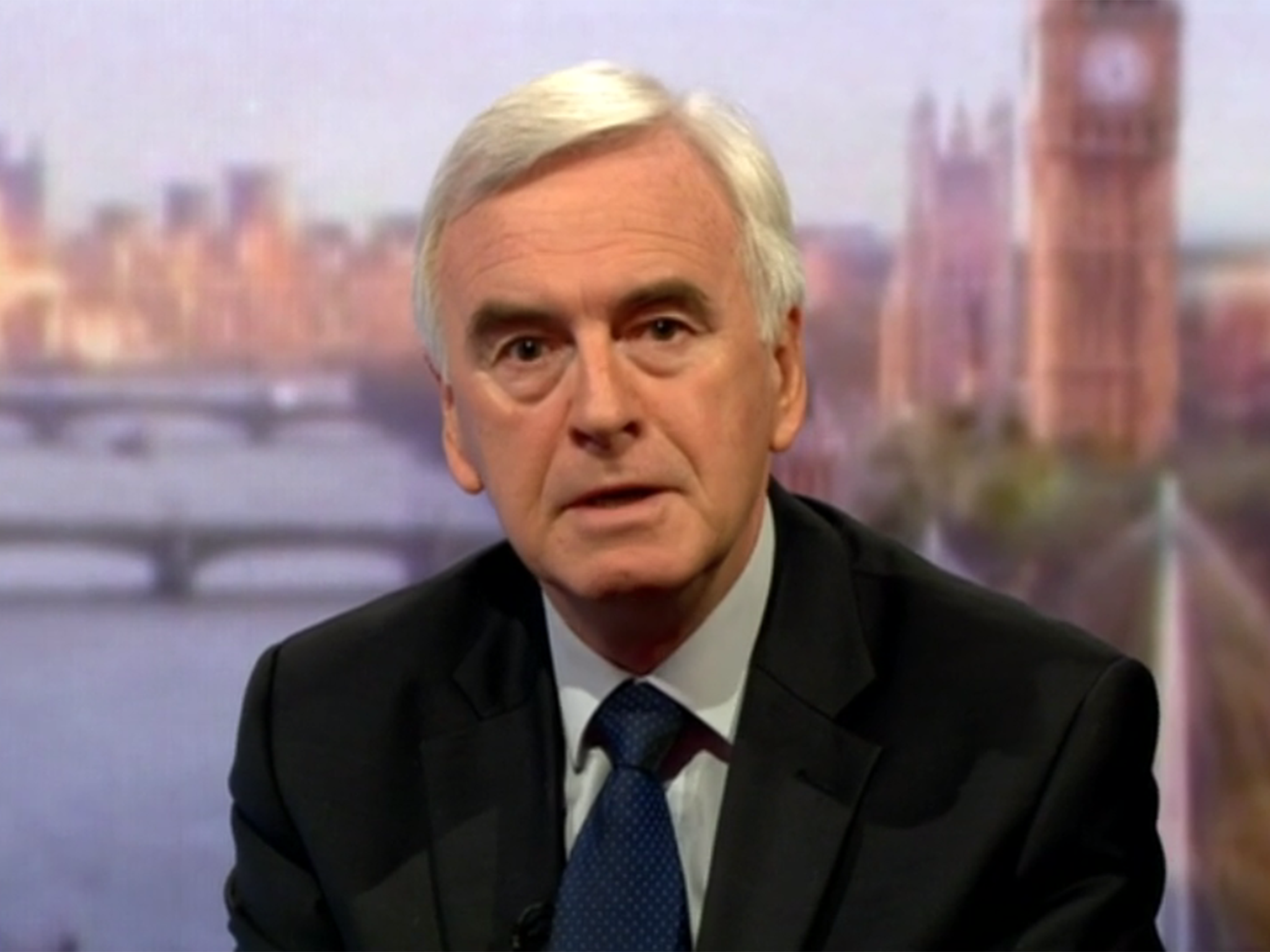

The shadow Chancellor John McDonnell this week has cited new technology as a reason why his party is looking closely at a Universal Basic Income.

The Bank of England’s chief economist, Andy Haldane, last year suggested that 15m British jobs could be automated.

Such is the buzz around the subject that one half expects to arrive at the office one morning to find C-3PO sitting there, typing away and answering the phone.

Yet the actual evidence of the rise of the job-taking machines is patchy and, in some respects, considerably overblown.

A much-cited study by two academics, Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, suggesting 47 per cent of jobs in the US economy are at risk of automation has been challenged.

According to an OECD report the figure is more like 9 per cent for advanced economies.

Driverless car technology is advancing fast and we have app technologies such as Uber that threaten a traditional industry. But take a step back and there’s very little evidence on an aggregate level of robots and computers yet displacing flesh and blood humans on any kind of scale.

The UK employment rate is at a record high. In France, Spain, Italy and Greece unemployment rates are painfully elevated; but that is due to catastrophic macroeconomic policies from European governments, not robots nabbing the jobs.

The US adult workplace participation rate has been falling since the turn of the millennium for reasons that economists don’t understand. But there’s really no compelling reason to think automation is a major culprit.

As was once said of computers, one can see the robot revolution everywhere except in the official statistics. There’s a bizarre quality, not only to the prevalent anxiety about something that hasn’t even started to happen yet, but also to the fretting itself.

Scrape away the sci-fi tropes and robotisation is simply another way of increasing our productivity (the time it takes to produce a given amount of economic output).

There is no substantive difference between robotisation and the invention of the wheel, the spinning jenny, the steam engine or the personal computer: these are all human inventions that boosted our productivity and shifted the shape of society.

As John Maynard Keynes pointed out in the 1930s, these technological developments are the means by which mankind is gradually solving our “economic problem” of needing to toil, often in unpleasant or boring jobs, to ensure mere survival. Robots displacing human labour isn’t the problem: it’s the whole point.

There’s another curiosity. Some economists are pessimistic because they think our current era of economic growth driven by technological advances is over (at least for now) and that is why productivity growth across the world has been so lacklustre in recent years.

Yet the robot worriers are pessimistic because they think precisely the opposite: that we are on the cusp of another industrial revolution and an explosion in productivity. Do they really think stagnation would be preferable? Indeed one might look at the flatlining of productivity and lament that humans are taking all the robots’ jobs.

So are we foolish to worry? Not entirely. While it’s true that, historically, technological advances have tended to lift living standards and opportunities for all, there have also been strains in the transitions (sometimes prolonged or violent strains).

And it’s not inconceivable automation could exacerbate income inequality if the economic fruits from new technology accumulate in the wallets of a privileged minority, rather than being broadly shared.

A socially destabilising glut of frustrated and surplus human workers – a “wealth of humans” in the title of one new book by the journalist Ryan Avent – seems unlikely given how history has unfolded until now, with new types of jobs created at each stage of development. But it’s not impossible.

This is one of the reasons why the case for a universal basic income is being pushed, and not only by old-school left-wingers like McDonnell. It may be necessary to go down that road. But then again it may not.

There is a danger that supposedly looming robotisation is used to justify redistributive economic policies that really ought to be considered on their merits given the state of technology and society as it currently exists, not as it might be in some unknowable future.

Another danger is that robotisation is presented, rather like “globalisation” is sometimes presented, as an inexorable economic force before which political leaders are helpless; that robotisation becomes a kind of excuse for the economic outcomes we have in our societies, despite the fact those outcomes could be ameliorated by adopting a different suite of policies on tax, investment and redistribution.

If we are unhappy with the shape of our societies and the opportunities for human flourishing that they offer (or don’t offer), then the fact is we always retain the power to change things. Let’s not fall into the trap of lazily blaming C-3PO.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments