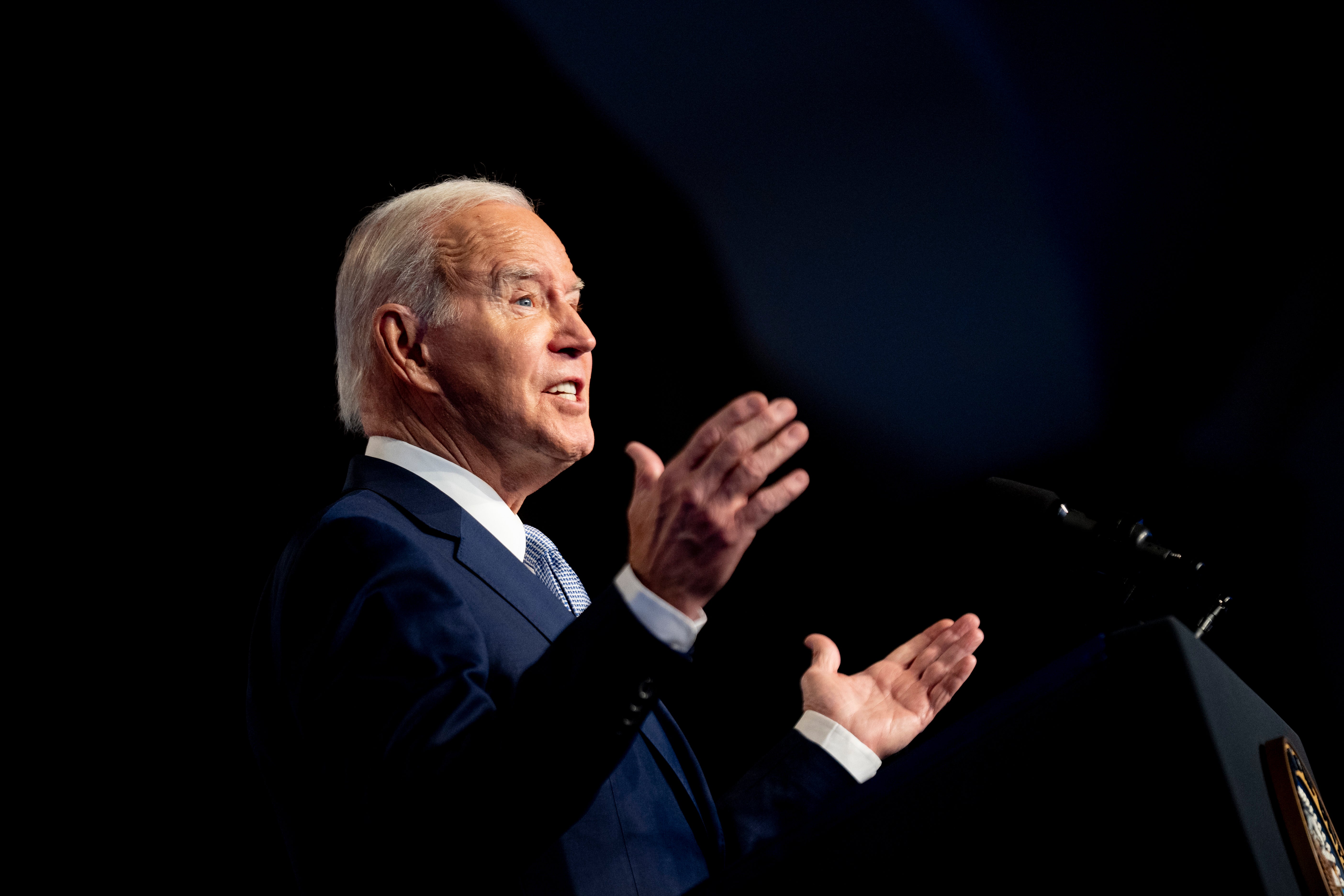

Could Biden’s age be his biggest barrier to a second term?

Can the 80-year-old president avoid making any big mistakes between now and election day, asks Mary Dejevsky

At four score years and five months, Joe Biden has announced that he will run for a second term – or, as we British-English speakers would say, “stand”, which might be more appropriate here. Were he to win, this would make him 82 on inauguration day and 86 by the time he left office, in the event that he served out his full term.

Now, I know a few people of similar vintage to whom I would happily entrust the power that resides in the Oval Office and the nuclear suitcase that comes with it, though I doubt they would relish the task. But anyone who argues that age will not be an issue in voters’ minds as the 2024 US presidential campaign gathers pace over the next 18 months is not living in the real world.

Of course it will be an issue. The question is what sort of an issue, and how hard it might be to surmount. It is probably fair to say that Ronald Reagan’s famous quip, when faced with the age question during his 1984 debate with Walter Mondale, has had its day. “I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience” was an ingenious pre-emptive strike then but will not work to similar effect again.

Not only was Reagan, at 73, almost a decade younger than Biden will be when the debates come around, but Americans now know, what they could not know then, that his last years in office were already marked by the sign of Alzheimer’s that was to blight his later years.

Then again, how dangerous can a US president be, even when he – or maybe one day she – is physically and/or mentally ailing? There are those who argue that the system is robust enough to cope with a failing president; that far more power is dispersed and constrained than might seem from the centrality of the presidential figure, and that everything can chug along quite satisfactorily (especially if the president has the actor’s instinct of a Reagan).

And just look, a supporting argument might run, at how the Washington establishment managed to keep the maverick, Donald Trump, effectively caged for so much of his presidency. This applied particularly to his campaign pledge of a rapprochement with Russia, but also to much else.

That some of the mechanisms used were spurious – the so-called Russia-gate claims (of complicity with Moscow) and the blame attached to Russia for the real entries on Biden’s son’s discarded laptop – only strengthens the argument. There are ways of keeping a wayward president in check, so age does not have to be the weapon that clinches the argument for a younger opponent.

Its force depends in part on how much younger any opponent might be and how well the Biden camp is able to play up the perceived benefits of age and experience, while playing down the liabilities.

Barring last-minute missteps, the Biden camp could certainly argue that he has played a steady hand during volatile times, that he has worked well “across the aisle”, that the Democrats’ better-than-expected showing in the mid-terms demonstrates that he can still win elections, and that the chaos of the Afghanistan withdrawal rests with his madcap predecessor, who decreed the exit policy.

A case can also be made – and is being made – that Biden’s stiff and sometimes stilted manner is just how he has always been and is nothing to do with age. Also, that public speaking was never really his thing – at least in the inspirational mode of John F Kennedy or Barack Obama – and that his strength resides in the empathy he can exude one-to-one (in part because of the personal tragedies, including the deaths of his first wife and elder son, he has suffered).

There does, nevertheless, remain a question. I recall listening to Biden’s statement and press conference after his low-key Geneva summit with Vladimir Putin in the first months of his presidency, and contrasting his rambling incoherence with the fluent clarity of the Russian president at his parallel press conference. If a US president sees himself and wants others to see him as the leader of the Free World – if no longer as global policeman – then he needs to carry conviction in that role. No number of state secretaries or advisers can do it for him.

There is also what might be called the FDR question. The protection of a failing or wayward president can go only so far. The extent to which the latter stages of the Second World War, and the negotiation of the Yalta agreement, might have played out differently had Franklin Roosevelt not been so ill is still debated. FDR’s illness, and his death, just 82 days into his fourth term, did, however, have at least two quite specific repercussions. One was to raise the importance of the running mate. FDR is said to have chosen Harry Truman, rather than his existing vice-president, Henry Wallace, in the light of who would make the better president.

For his first run, Biden could (just about) afford to “balance” his ticket, and chose Kamala Harris, a woman of colour. Having not shown herself particularly credible presidential material, might she be replaced for Biden’s second run? Could he lose votes without a running mate more evidently equipped to take over?

The other direct consequence of FDR’s presidency was the 22nd amendment to the US constitution, passed in 1947, which limits a president to two terms. It can be debated as to whether this is too little time to deliver on campaign pledges – both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama might well have won third terms had they been allowed to run. But there is no appetite for change.

What that amendment failed to envisage, however, was what happens when a president’s first term begins only when he is well into his seventies. The constitution sets minimum ages to run for the US House of Representatives (21), for the Senate (30), and for president (35). but there is no maximum. The late Strom Thurmond turned 100 before he left the Senate. The oldest senator at present is Dianne Feinstein, at 89. Depending on how Biden’s second term, if he wins one, pans out, could there be agitation for an upper limit for elected office?

First, however, Biden has to win that second term, and while age will be a big factor, how big a factor will also be determined by who becomes the Republican nominee. If it is Trump, then the age gap, at three years, would be less important for many voters than what they might see as the wisdom gap. This is how Biden won in 2020. A younger, less Trump-like nominee, could force the age issue back into prominence and contribute to a different outcome.

In a way, it is surprising how the leadership line-up of the United States, a country that so often prides itself on a youthful image, has started to resemble that of the early 1980s Kremlin. And it is worth noting the galvanising effect on US politics, both of JFK’s presidential bid, and of the Clinton-Gore ticket of 1992, when Clinton rejected advice to choose as his running mate an older, more experienced hand to face the incumbent, George HW Bush. Were Trump and/or Biden not to run next year, the political landscape could change as dramatically again.

In the meantime, Biden’s announcement should perhaps be placed in its narrower context. Had he decided not to run, he would have become a lame duck president at once, and the party would be airing its differences in public – rather than more quietly, as now – as rival contenders jockeyed for the crown. By stating his intentions early, Biden has also piled the pressure on the Republicans to make their choice, even as Trump is embroiled yet again in the justice system.

But it is a long time until 5 November 2024, and the way goes via one of the most punishing election campaigns anywhere in the world, even as the questions pile in. Can he avoid big mistakes between now and then? Could he be sunk by his errant son? Even if he has the drive for a second term, will he have the energy, the resilience, the health to fight on? And, even if he believes he does, will a sufficient number of voters agree? If the polls start to say they do not, Joe Biden could find that his campaign meets an early end.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments