The Jason Aldean video is just the tip of the country music iceberg

‘Try That In a Small Town’ sums up what many have wanted country music, and this country, to be

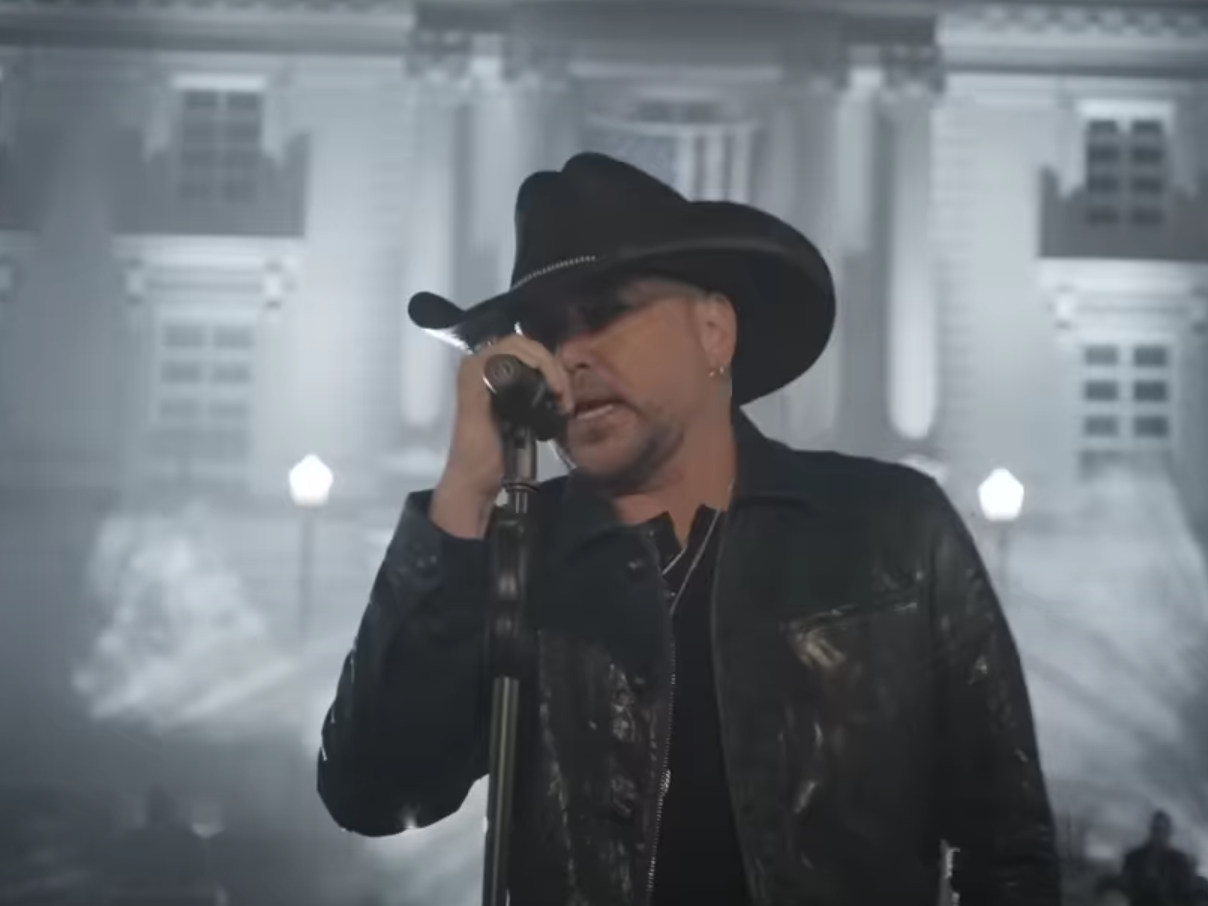

The video for Jason Aldean’s “Try That In a Small Town” has been pulled by CMT.

The company didn’t say why, but presumably it’s because the song encourages violence against protestors. “Cuss out a cop, spit in his face/Stomp on the flag and light it up/yeah, ya think you’re tough/Well, try that in a small town” Aldean boasts as the band slogs through the charmless and largely tuneless mid-tempo arena retro rock. In the video, scenes from the Maury County Courthouse in Columbia, Tennessee are flashed onscreen; that was the site of the 1927 vigilante murder of a Black man named Henry Choate. One commenter on Twitter called the track a “modern lynching song.”

In response to the backlash, Aldean has insisted that the video doesn’t reference race and doesn’t encourage violence. But it’s hard to deny the belligerence of lines like: “See how far ya make it down the road / Around here, we take care of our own”. Who gets taken care of in Aldean’s vision? Black people protesting police violence? Or cops committing that violence?

Aldean’s video presents white rural community as intrinsically virtuous and under threat from nefarious outsiders. That’s a volatile myth—and one which resonates with the legacy of white backlash in the US in unpleasant ways.

It also resonates with country music’s own history. Country was in fact created around whiteness. In the 1920s, record executives at virtually all the major companies started to separate Black and white rural music into segregated categories: race records and hillbilly music.

The marketing distinction didn’t stop Black and white performers from influencing and even occasionally performing with each other. But it did codify and perpetuate country as a white dominated genre, which borrowed from Black musicians, but rarely centered them.

When Black country stars emerged, they were often forgotten over time (see harmonica wizard DeFord Bailey) or nervously bracketed, like Ray Charles. Charles’ 1962 record Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music was a huge hit. But he was only inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2021. That’s almost 50 years after his classic album, 17 years after his death, and a year after the George Floyd protests. At that rate, we can expect the Country Music Hall of Fame to induct Lil Nas X sometime in 2050, at the earliest.

Country’s white identity politics have also sometimes made their way into its music and lyrics. In 1966, country star Marty Robbins independently recorded the pro-segregationist song “Ain’t I Right,” a vicious attack on Civil Rights organizers which labeled them all a “bearded, bathless bunch” of communists. “Why coddle tramps that march out in our streets?” he fumed—an ominous sentiment given the fact that Civil Rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerener, and Andrew Goodman had been tortured and murdered by the KKK two years previously.

There are numerous other examples. In 1977, Merle Haggard recorded “White Boy,” a song in which he says he’s a white boy who “doesn’t want no handout livin’”—not very subtly implying that Black and Asian people are lazy, and do. Johnny Cash was, in general, a progressive force in country music, but his 1982 “God Bless Robert E. Lee,” which praises Lee for ending the Civil War, is an unfortunate misstep. Hank Williams Jr’s 1988 “If the South Woulda Won” is even worse; Williams fantasizes about a Confederate state in which criminals would “swing quickly,” cheerfully evoking lynch law. Charlie Daniels’ post 9/11 nationalist anthem, “This Ain’t No Rag, It’s a Flag” mocks Muslim head coverings. Post-2020, Christian country singer Natasha Owens released the election denying anthem “Trump Won”. And so on.

This isn’t to say that all country music inevitably embraces white identity and reactionary racism. There’s a progressive, antiracist tradition in country too, from Jimmy Rodgers collaborating with Louis Armstrong way back in 1929 on a song about being hassled by cops, all the way up to Rhiannon Giddens in 2017 singing about the brutal experiences of Black women under slavery. Country has always had many Black fans, and there have always been Black performers including Charley Pride, Otis Redding and Beyoncé who have recorded in the tradition — albeit often with ambivalent support from Nashville.

So there are countercurrents and counter country traditions. But the fact remains that Aldean’s angry cocktail of nostalgia, country music, and an implicitly white conservative status quo is very much in the mainstream of country music tradition and country music politics. The genre has always been enamored with the idea of white community, and has often figured white people as the pure defenders of American values and America’s heartland against a dangerous cosmopolitan leftist conspiracy of antiracist rabble-rousers. “Try That In a Small Town” isn’t everything that country music is. But in its reactionary defense of a white status quo, it sums up what many have wanted country music, and this country, to be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks