‘The mood of society has changed’ – Iran faces a pathetic turnout at this month’s election

A recent survey suggests only 41 per cent of eligible voters plan to cast ballots in the 18 June contest to succeed President Rouhani. Why, asks Borzou Daragahi

The Iranian presidential election is approaching and judging by poll numbers, even those published by state media, enthusiasm nationwide is dismal. A recent survey conducted by a state-backed polling organisation suggested that only 41 per cent of eligible voters plan to cast ballots in the 18 June contest to succeed the incumbent, Hassan Rouhani.

An extensive study conducted by the organisation Gamaan yielded numbers that were yet more abysmal, suggesting that only 25 per cent of voters will show up at the polls. That’s pathetic for a country that has for 42 years aspired to be some kind of democratically anchored Islamic utopia.

Such numbers are even more extraordinary when considering that Iranians often fear that failing to vote – and obtaining the requisite stamp in the identification booklet that serves as a birth certificate and family record – could mean retribution at work or at university.

Many of Iran’s faults can arguably be attributed to the actions of its avowed enemy, the United States. Its economy is in a shambles in large part because of sanctions imposed by America. Its relations with other world powers have also been complicated by Washington’s decision to pull out of the 2015 nuclear accord.

But the disintegration of its already deeply flawed democratic trappings are almost exclusively the fault of one man, the supreme leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, and the hardliners who have in recent years tightened their control over the country’s security, intelligence and judiciary systems.

Iranians have for years used the ballot box as well as the streets to send the message to regime stalwarts such as Khamenei that they don’t agree with his vision for the country, and that they seek an Iran that is more free and more open to the world. However, the regime’s leadership has failed to heed the people’s warnings, instead doubling down on political repression, with surveillance, internet blockages, arrests, and even executions of domestic political opponents.

Hopes that even marginally progressive or moderate elected officials could loosen social restrictions and open the political space have been thwarted at every turn. That has profoundly damaged Iranians’ quarter-century quest for gradual, peaceful change within the Islamic system under avowed reformists such as the former president Mohammad Khatami or even relative moderates such as the soon-departing Rouhani.

“This is the first time you can see the targeting of the regime, as opposed to just conservatives or hardliners,” says Ammar Maleki, the Netherlands-based scholar who oversaw the study for Gamaan. “The mood of society has changed.”

The ageing jurists of the Guardian Council, which serves as a sort of constitutional court that vets the nation’s candidates as well as laws for adherence to Islamic standards, have exacerbated Iran’s democratic crisis. Likely acting on the hints and gestures of Khamenei, they excluded all but six obscure, third-rate or minor candidates for the presidency in what appears to be an attempt to pave the way for the supreme leader’s favourite: the hardliner Ebrahim Raisi.

Forget Zahra Shojaei, the women’s activist who sought to be Iran’s first-ever female president. Even former parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani, who has served as a reliable lapdog of Khamenei, was excluded for not being up to the standards of the Guardian Council.

Raisi, an alleged human-rights violator who is accused of being a member of the body that ordered the mass murder of thousands of political prisoners in the late 1980s, lost in a landslide to Rouhani in 2013. He has performed pathetically at a series of televised debates meant to drum up enthusiasm for the elections. In hours of discussions, he has yielded not a single memorable soundbite or one-liner. He was even outshone by the dull, didactic Saeed Jalili, the former nuclear negotiator.

But the black-turbaned 60-year-old cleric apparently has the requisite resume to become a rallying figure for hardline regime acolytes should the 82-year-old Khamenei die. Despite his lack of charisma or even much political experience, Raisi’s photos and banners are overwhelming the streets of Iranian cities, a sign that intelligence and security apparatus operatives and fanatic pro-regime paramilitaries are mobilising the vote for him.

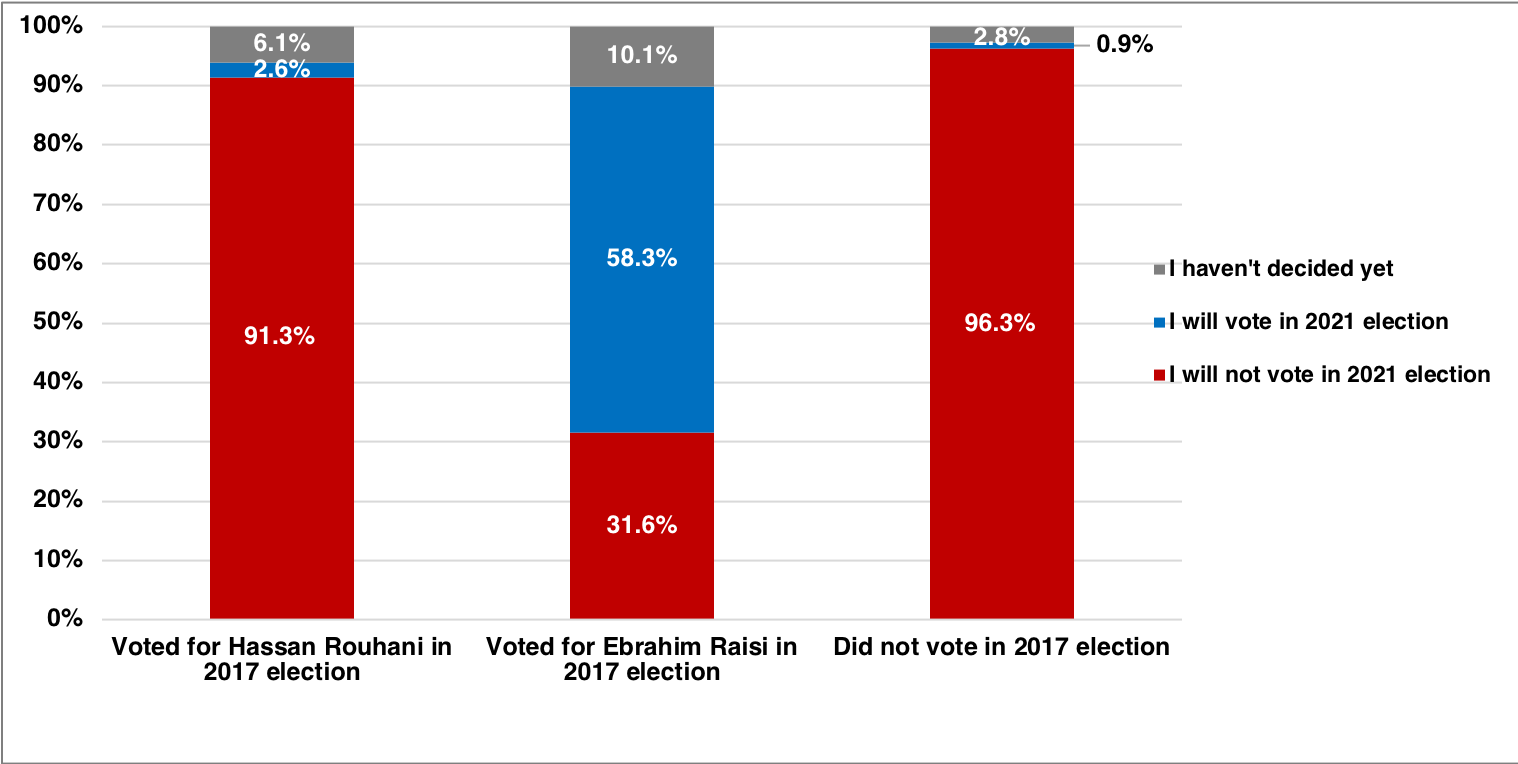

The enthusiasm gap between hardliners and the rest of society is stark. In 2017, Rouhani beat Raisi by 57 per cent to 38 per cent amid a 73 per cent turnout. According to the Gamaan survey, which was conducted between 27 May and 3 June, only 9 per cent of those who voted for Rouhani in 2017 will vote this year, while 58 per cent who voted Raisi say they will turn up at the polls on Friday.

Should overall turnout numbers be too anemic, the regime could always fudge the final figures to make them sound more respectable, something they’ve probably done in the past.

This might make hardliners feel more secure when they gather to swear their loyalty to the regime at weekly Friday prayers in Tehran, but none of it will solve problems that have prompted rounds of mass street protests with increasingly revolutionary tones.

As long as there was a hope for political change as well as a measure of economic prosperity, Iranians were willing to set aside their democratic aspirations. Without that hope, Raisi will be running an angry, demoralised nation willing to entertain a radical transformation.

Offered a list of imaginary candidates in the Gamaan survey, 29 per cent of respondents said they would vote for Reza Pahlavi, the Virginia-based son of Iran’s last monarch. Only 15 per cent said they would vote for Raisi.

“Changing the regime has become the main channel for having any kind of change,” says Maleki. “Many are coming to the conclusion that the first precondition of reform is changing the regime. It doesn’t mean the regime will collapse in six months or a year. But it’s an important indicator that you cannot ignore.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments