The secret to reading the most complex literary classics

There's no such thing as 'too clever books', writes former English teacher, PhD researcher, editor, writer and recovering bibliophile, Ryan Coogan. No, not even Ulysses...

There’s something very quaint about being intimidated by a book.

Don’t get me wrong, we’ve all been there. We all have a volume in our collection that we bought on impulse, but can’t imagine ever actually sitting down and opening. Maybe it’s by an author who has a reputation for complex prose. Maybe it’s about a topic we haven’t encountered before, and we don’t feel we have the required background knowledge to properly engage with it. Maybe it’s a 900-page monster, and we can’t summon the courage to approach a tome whose sheer heft could probably kill a man if dropped from a substantial height.

But as a former English teacher, PhD researcher, editor, writer and recovering bibliophile, let me tell you a secret: books are more scared of you than you are of them.

(Or maybe that’s spiders. Either way, the point stands.)

I grew up in an area where reading was regarded with suspicion at best, and punitive action at worst, so my relationship with literature has always been complicated. By the time I was 17 and university was on the horizon, I had a vague idea that I wanted to study English, but I was a solid C-student (on a good day), so I’d made my peace with the fact that there would always be certain books that would remain off limits to me. I wouldn’t be dabbling in Dostoevsky. I wouldn’t be tackling Tolstoy. I wouldn’t be… kicking it… with… Kafka? That last one wasn’t as good.

My college library had a couple of shelves dedicated to the “Everyman Millennium library”, which was a really beautiful collection of classics in hardback. You had your major players – Dickens, Shakespeare, a handful of Brontes, etc – but there were also all these authors I’d never heard of before. Who was Marcel Proust? Or Nikolai Gogol? Is that man’s name literally “Balzac”? Surely that isn’t pronounced the way it’s spelled? (Reader, it was pronounced exactly the way it’s spelled).

The collection, which remained more or less untouched (it wasn’t a great school), was a constant reminder not just of how much I’d never get around to reading, but of how many supposedly canonical texts I’d never even heard of. I had visions of going to a university full of people who didn’t get beaten up for reading Goosebumps in the playground, and being made fun of for not knowing who Anna Karenina was (she plays tennis, right?).

If you’re familiar with undergraduates, you’ll know this fear was more or less totally unfounded. University is for protesting about social issues you only just found out about that morning – avid readers are the outlier, not the norm. But I didn’t know that at the time – and they hadn’t invented smartphones yet, which meant my attention span hadn’t been completely decimated – so I spent the rest of the year checking out books at random and trying to read them. I started with books I was vaguely aware of, that were sub-200 pages, and gradually started to work my way up to thicker and more complicated volumes.

Here’s the thing about jumping straight to 19th century European realism when the most advanced book you’ve read so far is the last Harry Potter: your comprehension is not going to be great. Most of the time I wouldn’t classify what I was doing as “reading” – really I was just scanning my eyes over the page, only taking in the odd sentence fragment here and there. If I could get my hand on a plot summary or set of SparkNotes, I’d sometimes read that, alongside whichever book I was currently in the middle of, just so I didn’t feel completely adrift – but in general I just tasted the words on the page, with the occasional moment of comprehension as a rare bonus.

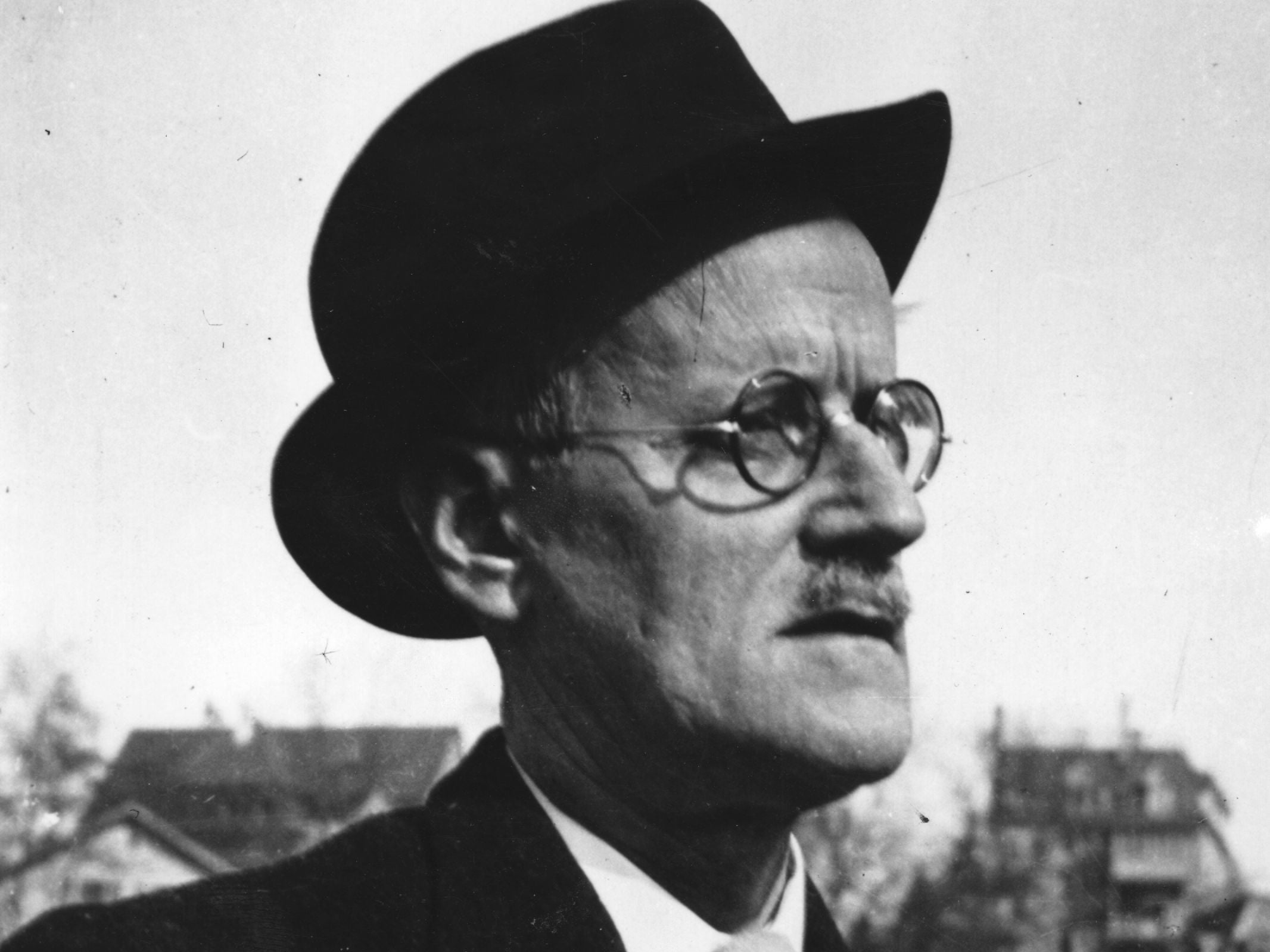

When I put it like that, it probably sounds like a waste of time, but I can’t recommend it enough. I “read” every James Joyce book in order, including Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, and took in maybe 1 per cent of what he wrote. I “read” In Search of Lost Time over the course of several weeks, and came out the other side with only a dim awareness of what had happened. I got a good few books deep into Emile Zola’s Les Rougon-Macquart cycle before I realised they were even supposed to be connected to each other.

But even though my comprehension was minimal, I found that the act of reading was in itself valuable. It sounds obvious to say, but it was like exercising a muscle, where even if you struggle in the exercise you’ll still find that you feel the benefits later on. Going back to “normal” books after you’ve read Ezra Pound’s Cantos in full becomes trivial (even if you did only understand three of the poems). Better still, when you come back to those really complicated books somewhere down the line – the ones you thought went completely over your head on a first reading – you’ll find that you got a lot more out of them the first time than you thought you did.

The benefits go beyond the act of reading, too. There’s something to be said for the confidence with which you approach other tasks once you’ve persevered with a 1000-page Modernist abomination. It made me a better writer, a better public speaker, and a more attentive student. It’s probably the only reason I still have anything like an attention span in a world of iPhones. Plus, there are the bragging rights of getting to tell people you read Ulysses (they don’t need to know that you have no idea what happened in it).

So dust off that copy of House of Leaves. Stop lying to people about how you’ve read War and Peace. Gravity’s Rainbow might be incomprehensible to you right now, but trust me – even if you don’t get much out of reading it, you’ll get a lot more out of it than you will if you keep letting it gather dust on your bookshelf.

So don’t be “intimidated” by books. No, not even that one. There’s no need to be afraid of words on a page. All you have to do is open it up, and start reading.

This article is part of our ‘independent thinking’ series in partnership with Nationwide. Together we’re celebrating independent thinkers past, present and future, and shining a spotlight on work which demonstrates perfectly what we define as independent thinking. This article is one such work, and we hope it’s got you thinking. If it has and you’re eager to continue, you’ll find more here.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks