I took these photographs on holiday in Syria in 2011. Now the places and people haunt me

Where are Mohammed and Rima now, after his city was destroyed and her town subjected to barrel bombing?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I hold in my hand two photographs. They’re only holiday snaps; I could have just looked at them on Facebook, but for some reason I decided to print these two out.

They were taken during the best holiday of my life, back in March 2011, in Syria.

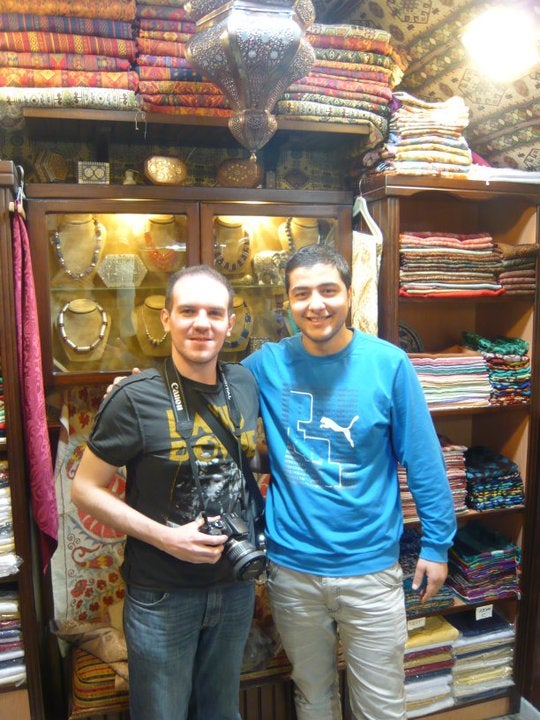

It feels odd looking at them now. The first shows me with my DSLR camera hanging around my neck, standing next to a slightly taller Arab man, also in his twenties, in a blue Puma T-shirt. We’re both smiling at the camera, our arms behind one another's backs in a comradely stance.

His name was Mohammed, and he worked in his family’s stall in the jewellery quarter of the grand souk in Aleppo, selling necklaces as well as fine silk scarves. My friend Rich and I met him while we were walking around the maze of shops, looking for the famous mosque. It was easy to get lost inside that souk, an ancient hypermarket filled with the smells of spices and the hum of conversations and the rattle of handkarts and tradesmen selling everything you could want to buy, as well as men and women and boys and girls from all walks of Syrian society.

Mohammed, polite and gracious and softly spoken, could see that we were unsure where to go and offered to show us the way to the mosque, and we gratefully followed, him asking us about London and we questioning Mohammed about Aleppo, Syria’s biggest city. We said our goodbyes at the gate, and walked in.

The mosque was magnificent, of course - with its great courtyard and the minaret that had stood for almost a thousand years - and after half am hour so, we happy tourists wandered back out feeling at peace, humbled by the history and its almost otherworldly spirituality. Soon, Rich and I were at risk of being lost once more, but after a few minutes we bumped into Mohammed again. He was pleased we had liked the mosque, and invited us back to his stall for a cup of tea and to show us his wares. Doubtless he also fancied a lucrative sale to a rare couple of western tourists - and if so, good on him, as I couldn’t resist buying a beautiful scarf from him.

There was a fair bit of friendly haggling, and then we shook hands. And before we said goodbye, Rich took that photograph of us smiling in Mohammed’s shop.

The mosque has been destroyed since then, and its minaret has toppled. The souk is gone - burned down. Aleppo has been wrecked.

The second photograph I'm holding was taken a day later in Apamea. While Palmyra has gained plenty of attention lately, Apamea was just as amazing in its own way: a road of Roman columns stretching further than the eye could see out in the middle of the Syrian countryside, a few hours’ drive from Aleppo, where the sound of grasses rustling in the breeze was interrupted only occasionally by the sounds of teenage boys larking about on battered little motorbikes.

This picture shows the columns stretching away in the blue-skied distance, and in the middle are two people posing for the camera: I'm one of them, and at my side a waif-like teenage girl, wearing jeans, a black top and Converse-like trainers, smiling innocently at the camera.

This was Rima. She must have been about 17, and we met her while walking along the collonaded road in our tour group. She and her friend had been walking a few metres behind us, evidently intrigued by foreigners and giggling while listening to our English voices. Before we left, Rima asked if she could have her photo taken with me. I said yes, and she smiled with a bashful pride when I asked if she would do the same for Rich's camera.

Many of Apamea’s columns have since been toppled, but far more seriously, the village where Rima lived has been barrel bombed - captured on camera by a documentary film crew.

But while I know from news reports what has happened to the places where Mohammed and Rima lived, I will almost certainly never know what has happened to them.

Every so often, when photos of Syrian refugees are shown in our media, I wonder where - among the mass of millions of people forced out of their homes - those two have ended up. They could be trying to climb across barbed wire to escape, or waiting outside a train station to find a new life - or mourning the loss of their child washed up on a beach. If they’re even still alive, that is.

These simple holiday pictures of Mohammed and Rima are important to me precisely because they show what we so rarely see. They show two of the real identities and personalities of the people we are shutting out and dismissing as members of migrant swarms - the shop-owners who took pride in their stalls, and the happy, carefree teenagers with their whole lives ahead of them. They were not always bound to be victims of a brutal civil war.

It took a picture of a dead little boy to wake many up to the urgency and tragedy of the refugee crisis. And perhaps that's because we're so used to seeing refugees - even when sympathetically - pictured as a mass of humanity, obscuring the individual human lives, and the stories of not just what desperate straits they are in now, but where they have come from, and why they deserve our help.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments