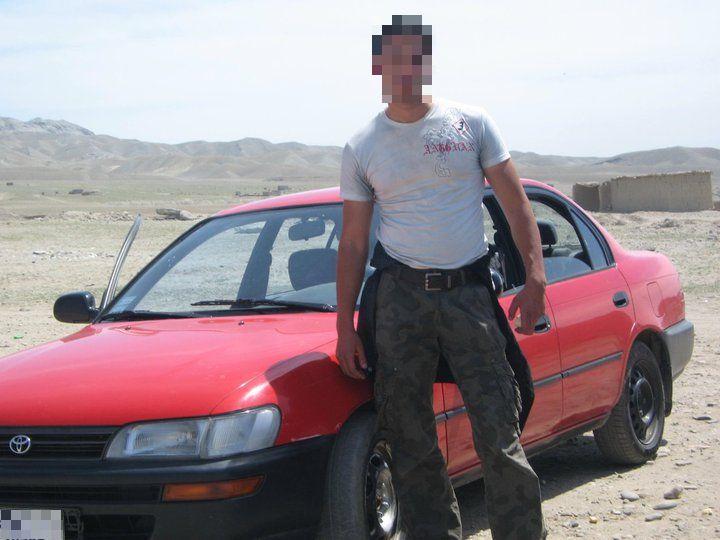

I helped Britain fight the Taliban as an Army translator, but now I'm a refugee the UK has abandoned me

By standing up to the Taliban, I was putting my family’s life in danger to protect British citizens. When the Coalition left Camp Bastion, I was sent back to my family village on leave, but the Taliban came looking for me

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As told to Matt Broomfield

Ever since I can remember I’ve lived with war, but I’ve never been more scared about my future than I am now. The Taliban has always had a strong presence in Laghman Province, Afghanistan, where I was born and where I went to school. So when I graduated from my political law degree in Kabul I went directly to the security company Titan, who employed me as a translator. In 2013, I began working with the US Special Forces.

Though the Americans were paying my salary, we carried out many joint missions with British soldiers in Helmand Province as part of the Coalition. By standing up to the Taliban, I was putting my family’s life in danger to protect British citizens. When the Coalition forces withdrew from Camp Bastion, I was sent back to my family village on leave, but the Taliban came looking for me. They came to my family home and they killed my father. At first I fled to Kabul, but Taliban agents followed me there, and I realised I had to leave.

If you want to work, it’s vital to be in a country where you can speak the language, so I never tried to seek asylum in any of the countries I came to: not in Iran, nor Turkey, nor anywhere across Europe. The journey was the hardest thing I’ve ever been through. As I made the crossing between Turkey and Greece I saw a boat go down with 55 people on board. But I made it across the Mediterranean without drowning, and up through Eastern Europe to Germany. I was only in Germany for two nights but the police caught me as tried to make my way towards France. I told them I was an English translator and had no plans to stay in their country as I don’t speak a word of German, but they forced me to give them my fingerprints before letting me go.

During the months I spent in the Calais Jungle, I played with my life every day. Once I fell while trying to jump onto a moving train and nearly died. When the French police caught me hiding in the back of a lorry, they dragged me out and beat me with batons. In May, I made it onto the back of a lorry again, but I was terrified the French police would catch me and give me an even worse beating than before. So I closed my eyes and prayed, and when I opened them I was in Dover. I went straight to the police station and turned myself in to the Home Office, as refugees are supposed to do.

Let’s be clear: ‘detention’ is just another name for jail. I committed no crime, but they put me in jail. They handcuffed me, though I told them I wasn’t going to try and escape as I am not a criminal. I developed a problem with my eyes that made it impossible to read letters from my solicitor, but they kept postponing and cancelling my medical appointments.

After three months, they released me, but now they have put me in a hostel in another large city. I know a few people in London, but here I have no-one. I’ve lost a lot of weight and I feel sick with fear all the time. Every fortnight I have to check in at the Home Office, and every time I’m scared they will put me back in detention. There are five of us living in one small room, and none of the others speak English, so we can only communicate through body language. The government solicitor has nowhere near enough time to help me, and I have no money to pay for my own lawyer. My only possessions in the world are one set of clothes that I’ve been wearing for six months, a pair of shoes and a cheap phone.

There is one other thing I still have with me from home: documents which prove I worked with the coalition forces in Afghanistan. But the Home Office won’t look at them because I was fingerprinted in Germany, and under current EU rules that means Germany is the only country that could give me asylum. I don’t know German culture, I don’t know the German language, and I never worked with any Germans. I told the Home Office I would cut off my fingers and send them to Germany before I went there, but they just laughed at me.

I’m 29 years old now and it would take me years to learn another language, but I could work here as a translator, or perhaps a fitness coach, and help the British people again. At the moment, my only job is sleeping, and I can’t even do that properly. I lie awake and pray because I’m terrified about what the future holds for me and my family. The last time I spoke to my mother was seven months ago. She’s unwell, and no-one is there to support her or my little brother and sister since I fled and my father was murdered by the Taliban. Can they still feed themselves? I have no idea.

Last year, another Afghan interpreter who fled the Taliban hanged himself because he was refused asylum. If the Home Office try to send me to Germany, I’ll kill myself. I know Germany is a great country, but I didn’t put my life on the line for German soldiers. I risked my life for the British and the Americans, and now the British government is abandoning me.

Ahmad Sakhi is a pseudonym

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article referred to Camp Bastion as Basra.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments