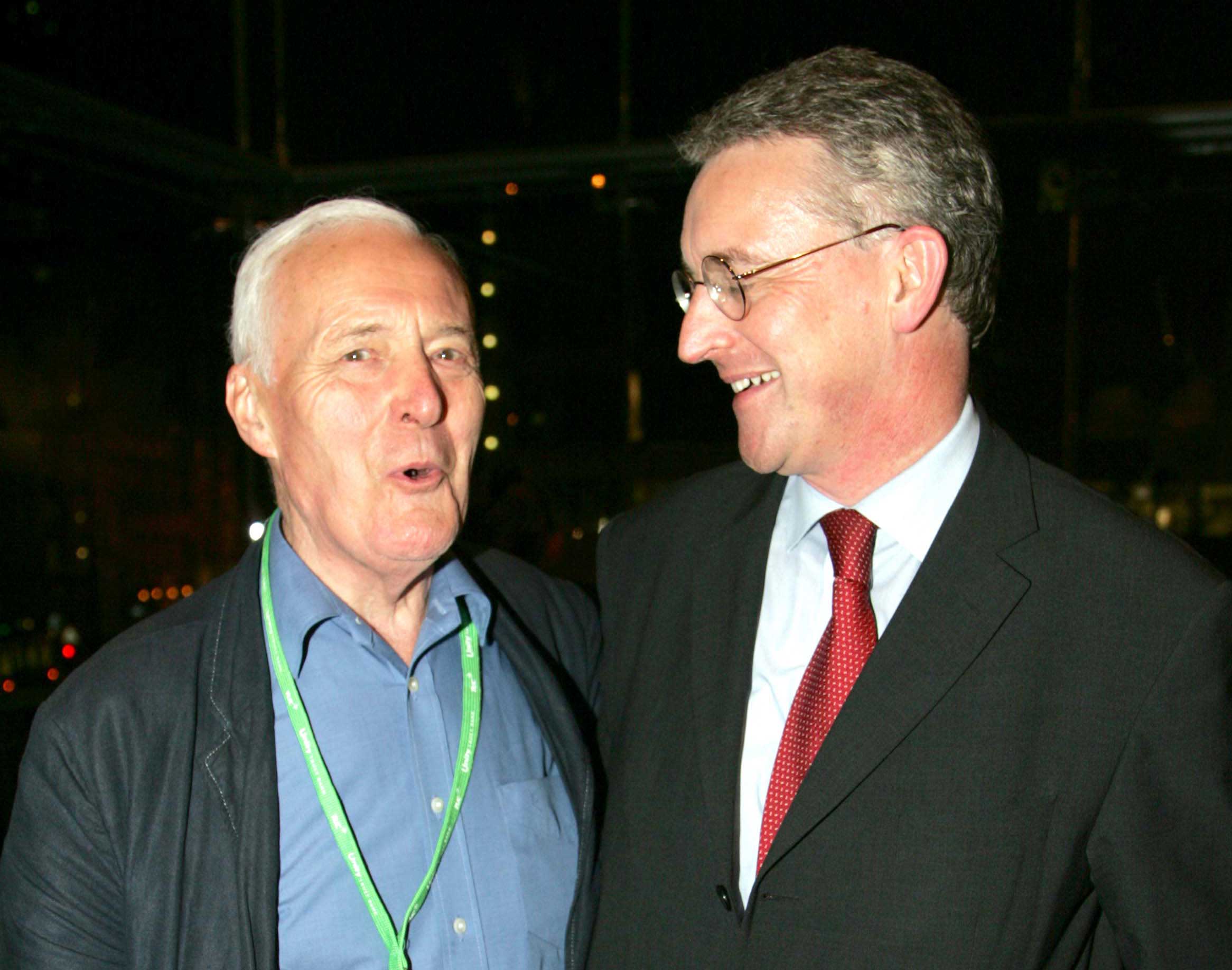

I asked Tony Benn what he thought of his son's vote on Iraq – and learned never to go there again

Like almost all fathers, there was nothing but pride there

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Four of the more blissful hours of my life were spent, in the autumn of 2004, talking politics with an elderly interviewee. When I report that he sipped seven cups of tea and puffed through as many pipe-bowls of finest shag, you will guess that the old gent in question was Tony Benn.

Among the matters discussed in his Holland Park sitting room that crisp October morning were George W Bush’s re-election chances the following month. Benn, a natural born optimist, was so convinced John Kerry would beat Dubya that he agreed to celebrate, in the event, by drinking alcohol for the first time in his life. “Yesh, all right, you’re on,” he consented. “I promish to take a glassh of beer.”

This sadly unfulfilled challenge having been accepted, the talk drifted to fathers and sons. Mustn’t it be agony for the elder President Bush, I said, to have such a warmongering klutz for a son? Sensing where that line of questioning might lead, a flinty glint flashed into his eyes. Not at all, said Tony Benn. Whatever their differences, he felt sure Papa Bush was proud of his boy. He himself profoundly disagreed about Iraq with his own son, who had voted for war the previous year. But paternal love is an infinitely more powerful force than any geopolitical discord. He was massively proud of Hilary and his rise through the Labour ranks.

For those few moments, unlikely as this may sound, there was a potent hint of Vito Corleone about the exquisitely courteous Tony Benn. (Three days later, a jiffy bag landed on my doormat. “I so enjoyed our chat, and felt I should return this, which you left behind,” read a note alongside a pack of Marlboro Lights containing two fags.) Don’t go there, he was warning. Do not dare suggest to me that, because we have political differences, I am ashamed of the son I adore.

How closely he could resemble Brando’s godfather I didn’t realise until a couple of days ago, when a friend mentioned a friend who was a friend of Tony Benn’s. When Hilary reached the Cabinet, this guy wrote to Tony to congratulate him on his lad’s promotion, appending a mild enough remark that it was a bit of a shame Hilary was so right wing. Tony would not speak to him for six months. When they next met, he icily fixed his gaze. “Never,” he said, “dishreshpect my family again.” So much for the popular notion, propounded on Twitter by Alex Salmond among others, that Tony Benn’s coffin is gyrating towards the Earth’s core in outrage at Hilary’s parliamentary tour de force in favour of bombing Syria.

The following is a smug argument I long ago vowed never to make. But what’s the point of being a columnist if you can’t break a solemn oath among friends? So I ask aloud whether Salmond, a faintly mafioso figure himself in the sweetest possible way, would be capable of such a thought were he a father himself. Perhaps he would. Perhaps, if he had a daughter or son who campaigned passionately for Scotland to remain in the Union, he would be ashamed of that child. For some fathers, it’s true: personal belief outranks parental love. But these are few; for most of us, there is little short of genocide a child could do to repel us.

Since my own son inherited a loathing of football through his maternal line, the test was never faced. But had he told me at seven that he had decided to support Ars**al, I would have coped. Had he later been signed by that club, and scored an 89th minute FA Cup final winner against Spurs, the tears of pride would have flowed in a raging torrent to wash away a lone tear of melancholy. This, I am certain, is how Tony Benn would have reacted had he been looking down on his baby boy’s triumph from the back benches on Wednesday night.

Of course, one wonders whether Hilary’s eagerness for military action is due in part to a subconscious rebellion against his dad. Freud might have analysed it in Oedipal terms. The philosopher Johnny Cash would explain his bellicosity by reference to “A Boy Named Sue”, his seminal 1969 treatise on the effects on the male psyche of a female forename. “Well, he must have thought that is quite a joke,” as the narrator reflects of his father. “And it got a lot of laughs from a lots of folk/ It seems I had to fight my whole life through/ Some gal would giggle and I’d get red/ And some guy’d laugh and I’d bust his head/ I tell ya, life ain’t easy for a boy named Sue.”

Life can’t have been easy at a London comprehensive in the harsher playground era of the 1960s, I tell ya, for a boy named Hilary. If he resented Tony for that, and expressed it by positioning himself on the opposite wing of the Labour Party, who could be surprised?

Yet unlike that Boy Named Sue, who “made a vow to the moon and stars, to search the honky tonks and bars, and kill the man who gave me that awful name”, Hilary was an unusually filial son. Others would have rejected more than the name (like Zowie Bowie, David’s boy, who reinvented himself as Duncan Jones). Hilary not only kept Hilary, he emulated Tony by becoming teetotal and vegetarian.

We are all of us – male and female – like our fathers in some ways, and unlike them in others. If some would prefer the Hilary balance rejigged, so that he ate chops and drank Scotch but echoed his father’s distaste for imperialist military folly, well, that’s really none of our beeswax.

And almost all of us who are fathers surely wish our children to be themselves rather than clones of us, even at the paltry cost of differing opinions. Vito and Michael Corleone had violently contrasting views about how to run the family business. In spite of that, the son worshipped the father, who was desperately proud of the son – and so it was, as it should have been, with the Benns of Holland Park.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments