Will spending £36bn on regional transport improve your daily commute? Don’t bank on it…

Cancelling the northern leg of HS2 won’t just disappoint passengers in Manchester, writes railway expert Philip Haigh – it could also make it harder for all of us to get around

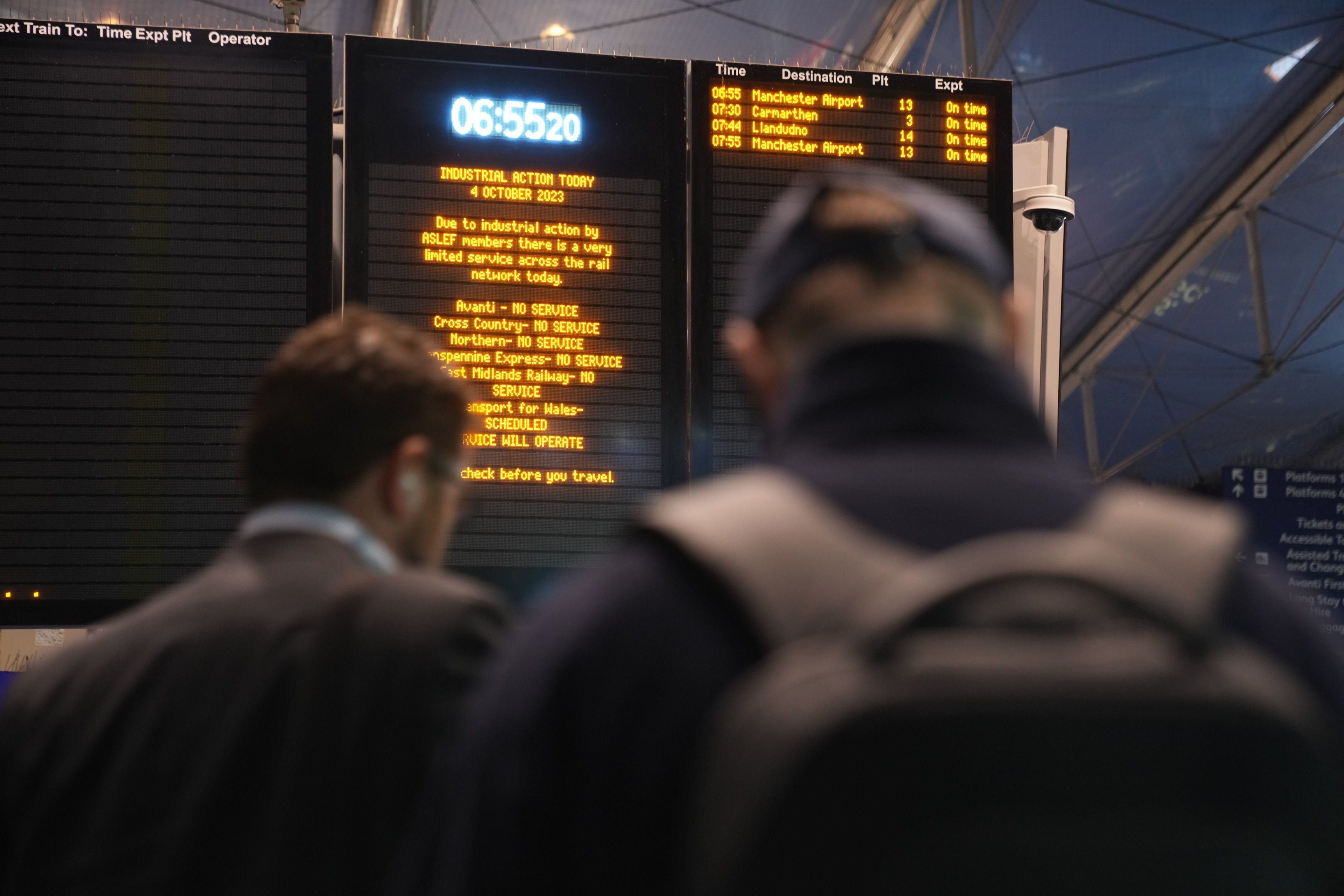

It’s a bittersweet moment for England’s railway passengers.

As the prime minister swings his axe into HS2, lopping the line to Manchester and the stump to the East Midlands, he’s gambling that the series of smaller, tactical transport improvements he announced – matching “every single penny” of the high-speed extension’s £36bn cost – can make up for his strategic retreat. Can they?

For starters, many more people use buses than trains, so Rishi Sunak’s pledge to extend the current £2 fare cap until the end of 2024 will help… if you can find a bus near you.

Better local transport improves everyday lives, there’s no doubt about that. But HS2 looked to solve a wider, deeper problem. It provides long-distance, trunk capacity. By taking the fastest of today’s London-to-Birmingham and London-to-Manchester trains off crowded lines, it creates space for more local trains and freight, which takes lorries off the roads. With one freight train carrying the equivalent of 76 motorway lorries, that was good news for anyone driving along the M6.

HS2’s importance to a stronger economy came from boosting capacity; speed was a by-product. If you’re building a new railway, it doesn’t take much more money or planning to build it for high speeds. HS2 planned to whisk passengers from Manchester to Birmingham in half the time of today’s trains, making it easier to travel for work or leisure. HS2 was never a commuter railway.

Sure, it made space for more commuter trains on today’s tracks, but it planned to make longer journeys easier, cheaper and more convenient. Businesspeople might use Zoom or Teams for meetings, but they also want to seal the deal in person. Friends and families might FaceTime, but you can’t hug a grandchild over a screen.

All of that is now denied to northern England. In its place comes a raft of smaller schemes – some reheated, some new.

To borrow Rishi Sunak’s phrase, we already have spades in the ground on the rail lines between Manchester and Leeds, as well as Manchester to Sheffield. He is not the first prime minister to promise faster journey times on these routes. A new tram system for Leeds has been on the drawing board for years, and a new interchange station for Bradford is long-promised.

Some projects look genuinely new: converting the freight railway from the steelworks at Stocksbridge, South Yorkshire, into a passenger line with trains to Sheffield Victoria and then on to Chesterfield via Staveley provides a link that doesn’t exist today. (Of course, Sheffield Victoria needs a new station; the old one closed in 1970 and was demolished years ago.)

Sunak’s plan to link Leeds and Sheffield with electric trains is better than running old diesels. But it is also very different to the government’s last great rail plan which, in 2021, proposed running electric trains south of Sheffield towards London. There’s no mention of that now; instead we’re heading north, towards Leeds.

Other projects have been pushing for cash for years. Uncorking the freight bottleneck at Ely in Cambridgeshire is one, and it is welcome. Meanwhile, campaigners in south-west England have been arguing for tracks to return to Tavistock, west of Dartmoor, for at least a decade. It’s only a few miles from Plymouth, so it really shouldn’t take a keynote speech from a prime minister to win permission.

That is perhaps at the heart of the switch from HS2; it feels strongly as if the prime minister’s team has scrabbled around looking for projects to put into his speech to replace the strategic project his party has supported for 15 years. Every one of those new, smaller projects is doubtless worthy, but they ought to be business-as-usual for a country such as Britain, birthplace of the railway.

Government is the art of balancing the needs of today, tomorrow and the next decade, which includes making long-term decisions for a brighter future. Sunak has not done that.

With the air of a conjurer, he’s concentrating on the here and now while not putting a timeframe on any of his local projects. Many will take years of further planning, and there’s no guarantee they’ll happen.

If you can cancel HS2 to Manchester after so many years of planning, you can cancel smaller projects even more easily, and with only local fuss.

There must also be questions about where the money is coming from. There are no short-term savings from cancelling HS2 because the government was years away from borrowing the money to build Manchester’s leg. Is it now going to bring borrowing forward to fund these latest local projects?

The prime minister is right when he says the “facts” over HS2 have changed. It’s a fact that more people made rail journeys last year than in 2009 when HS2 planning started. That’s why Britain needs the trunk capacity that HS2 promised.

Philip Haigh is a former deputy editor of ‘Rail’ magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks