This will change the way you think about women’s contributions to history

Annabelle Hirsch’s new book A History of Women in 101 Objects is a playful, intelligent and incisive look at the marks and impressions women have made throughout time, writes academic and writer Julia Bell

One of the most moving historical objects I have encountered was in the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. It was a small wooden box, which would have contained the possessions of an Irish orphan girl, perhaps as young as 14, who had been sent out to the colonies to escape the horrendous conditions of the Great Famine that would go on to claim over a million Irish lives and displace over a million others.

Transportation was also a colonial convenience; the arrival of young, hardy, fertile girls would not only provide domestic workers, but wives for the ex-convicts, who were expanding the reach of the colonial project into the hinterlands of New South Wales, farming the once-indigenous lands. At the time, the ratio of men to women was eight to one.

Here, in this small box, was the evidence of a life, a person, now lost to history, who had been chosen by the authorities for being young, single, obedient, “morally pure” and free of smallpox. I stood in the museum for a long time and wondered at the life that had once been attached to that object. What it must have been like to travel that then-unimaginable distance on a ship, to have little or no control over your own destiny, and to have arrived against any will or volition in a strange new place on the other side of the world.

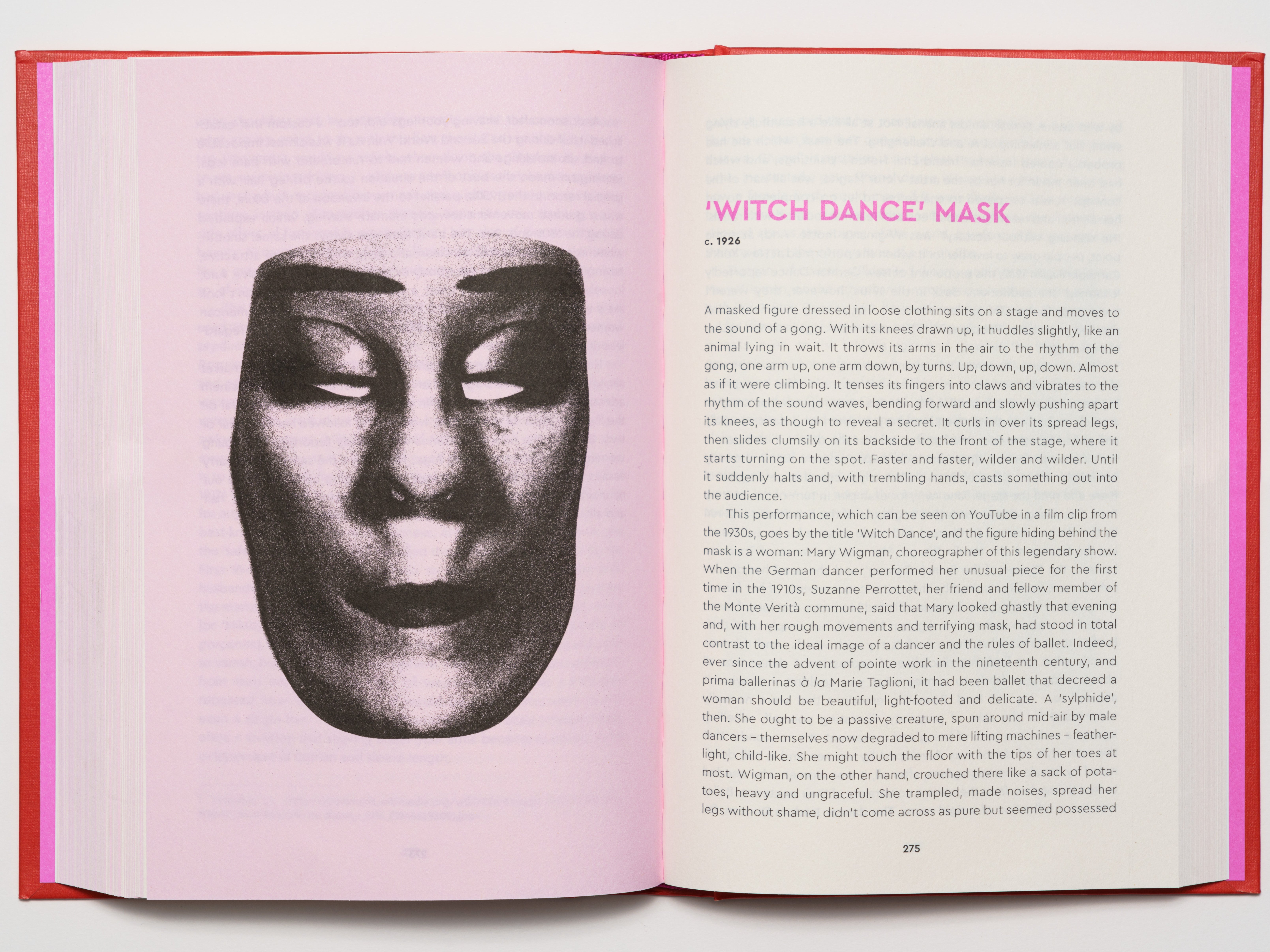

Material objects, perhaps even more than written stories, can connect us viscerally to the past – a fact which Annabelle Hirsch acknowledges in her playful, intelligent, expansive book A History of Women in 101 Objects. The book is a counterpoint to Neil MacGregor’s bestselling A History of the World in 100 Objects, a spin-off from the BBC Radio 4 series of the same name, which took items from the British Museum and used them as a platform to deliver a version of world history. Here, Hirsch is giving us the story of the female experience as “a compendium of women and their things”.

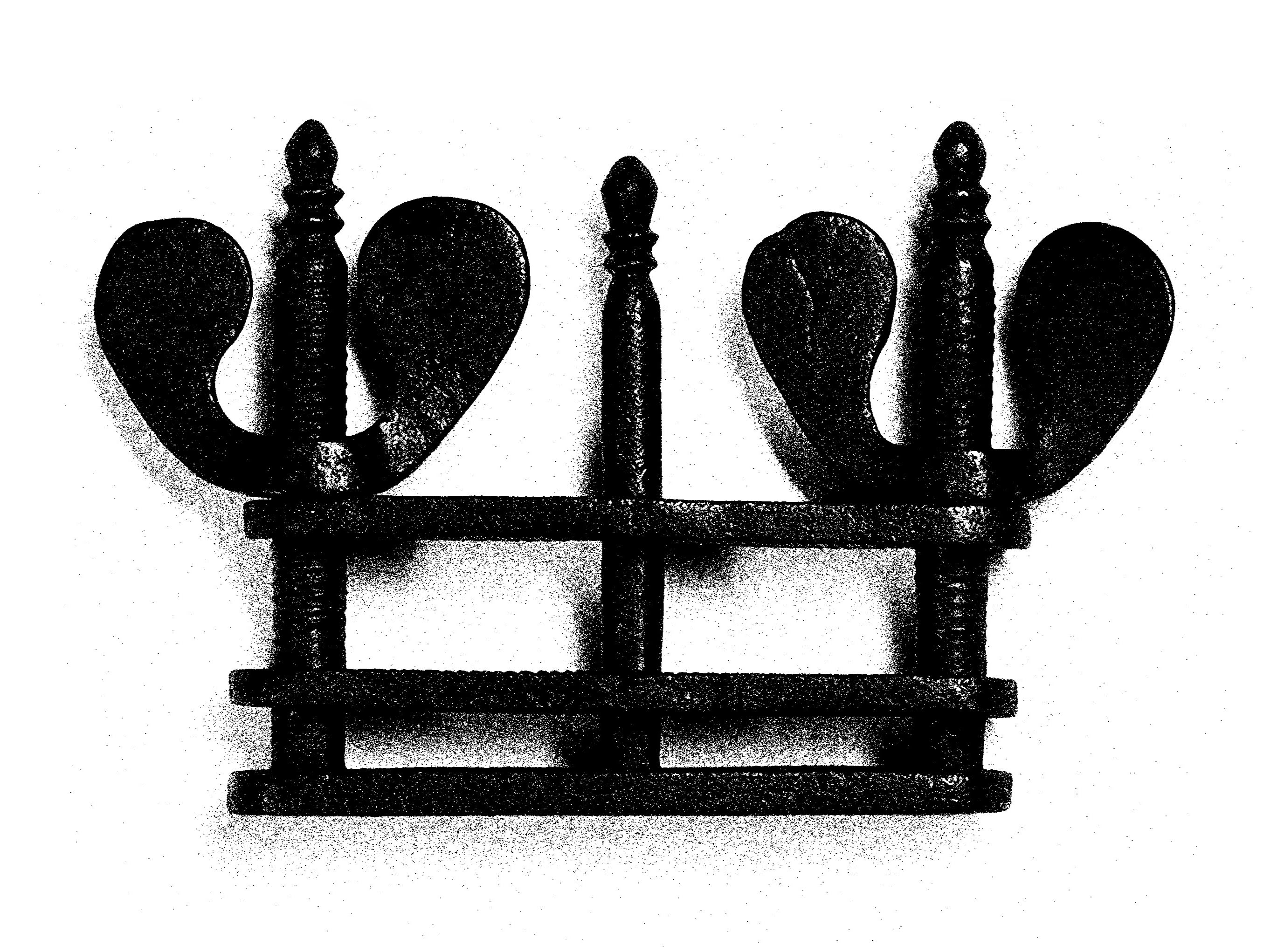

She chooses judiciously, hanging the story of 17th-century Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi on a pair of thumbscrews – why not a painter’s brush we might ask, until we are told how Gentileschi was subject to trial by thumbscrew to ascertain whether her accusations of rape against Agostino Tassi were true. The thinking being that, if a woman could stick to her story even while her thumbs were being crushed, she was telling the truth.

Unusually for a woman at that time, she won the trial, but it’s excruciating to think of her painter’s hands subject to such torture. No wonder her later paintings were so full of rage; in particular, her best-known masterpiece, the famous painting of Judith beheading Holofernes: you can almost hear the knife being plunged into his neck.

The book begins in the dreamtime of our deep past, which immediately provokes questions about who writes history, and who gets to interpret these objects. A 20,000-year-old cave painting of hands from Pech Merle in France turns out not to be, as previously assumed, the hands of men – at least 75 per cent of them belong to women.

Perhaps most interesting is the response to the 10th-century Viking grave in Birka, Sweden, where in 2017 DNA testing proved that one of the skeletons, buried with many objects, weapons and jewellery, was in fact that of a woman. Previous versions of history had assumed that any burial that contained so many weapons must have been of a high-value warrior, and therefore a man. This discovery turned our ideas of Viking society on its head.

In her introduction Hirsch tells a story of when she was at a dinner party explaining her project, to which one of the guests, “an elderly gent brayed loudly, ‘Women and objects? But women are objects!’.” Cue the collective groan.

To embark on a project like this is to inevitably unpick long histories of female oppression and servitude. The invention of the printing press, for example, did not immediately liberate women; in fact, it led to the spread of books such as Malleus Maleficarum or The Hammer of Witches, a book that sold 30,000 copies throughout Europe and triggered widespread panic about witchcraft. The consequence of which was the execution of around 60,000 people, two-thirds of them women. Hirsch quotes historian Michelle Perrot, who once said women at this time were the “scapegoats of modernity”.

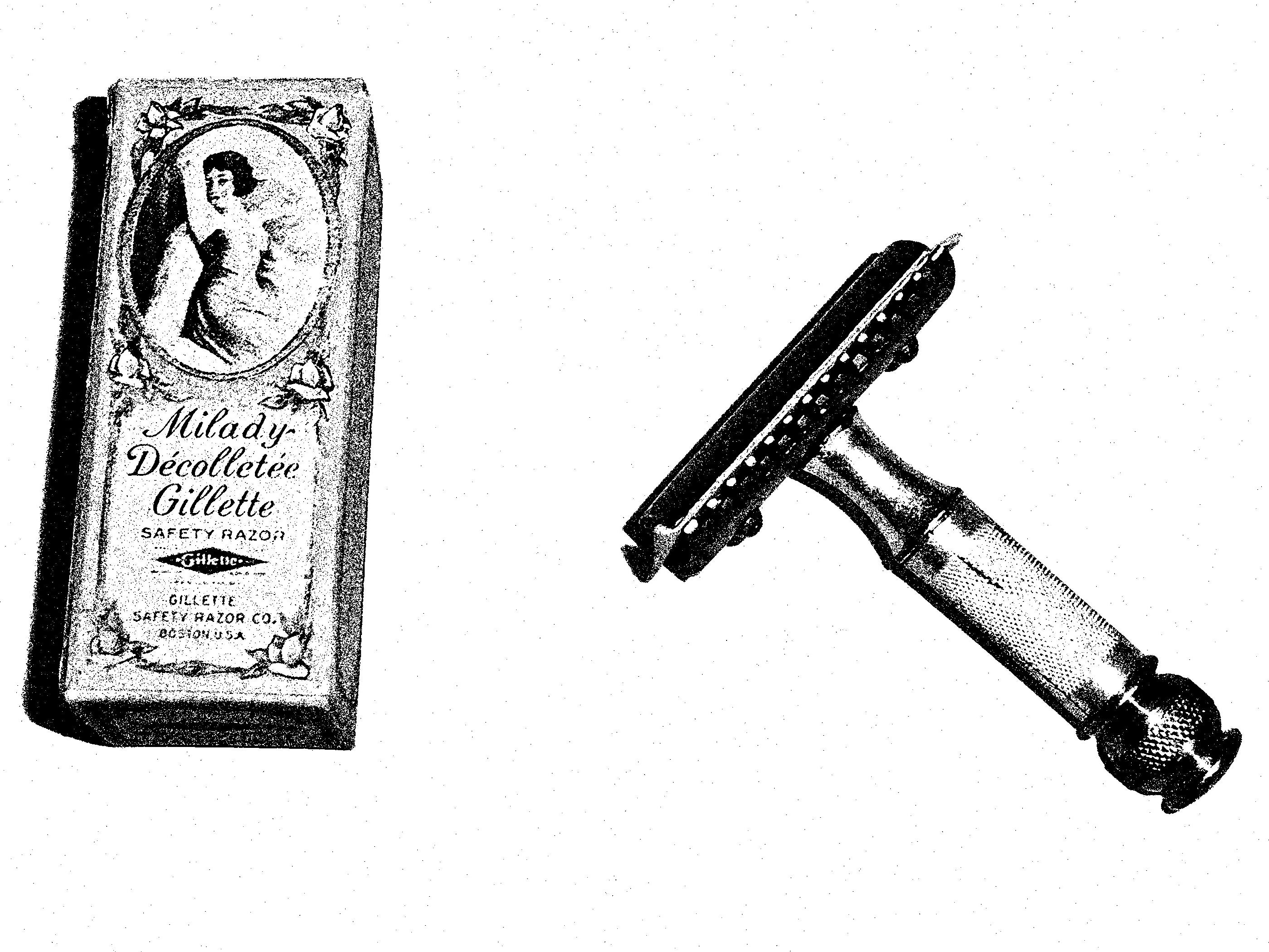

Many of the objects are from the boudoir, or the toilette: we have lipstick (“Le Rouge Baiser”), Chanel No 5, Milady Décolleté Gillette razors, especially designed for removing underarm hair. This points to the paradox John Berger articulates in Ways of Seeing when he says: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” And many of these objects reference and discuss this impossible position of trying to develop a subjectivity while being classified and objectified by men.

Consequently, many of these objects are also attached to acts of courage and resistance, and it seems appropriate that the book ends with two of these – the pink pussy hat from 2017, which became a symbol of the women’s marches that followed the election of Donald Trump, and a bunch of hair which symbolises the protests against the forced wearing of the hijab following the death of Jina Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Iranian morality police. This death provoked mass protests across Iran, and then the world, under the banner of “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (or “Women, Life, Freedom”). Protests which are still ongoing – to liberate Iranian women from the gender apartheid forced upon them by the Islamic regime.

Inevitably, in a book written by a French-German academic and translated from the German, this is a Eurocentric history. There are few objects from the global south, or which really represent the lives of women under colonialisation – the box from Hyde Park Barracks might have made an interesting addition.

But even the fact of its Eurocentrism decentres this from projects such as Neil MacGregor’s – namely that the British Museum is world history – rather than simply a version of it. Hirsch chooses some wonderful examples from French history – Madame de Pompadour and Madame de Stael both feature, along with the salons held by wealthy Parisian women. There is a very amusing section on the bidet in which we are treated to the Marquise de Prie from the court of Louis XV entertaining guests in her boudoir while seated on her bidet.

The book was recently released as an audiobook, with each object narrated by a famous woman, from Olivia Colman, Gillian Anderson, Helen Mirren, Maggie Smith and Kate Winslet, among many illustrious others, with profits going to Refuge. For a book such as this to be read in such a way is the perfect outcome for the project, baring perhaps an actual exhibition where it might be possible to see some of these objects in their three dimensions.

What is clear when reading this as a linear history is that periods of relative liberation for women always seem to be followed by repressive backlashes, which might serve as a warning in our current troubled times. Freedoms which are often taken as given are never secure, and economic circumstances often dictate how much freedom women can have at any given time. The overall story is one of struggle, resistance and brilliance, studded with wit and knowledge. But the message is that our freedoms are always fragile, always contingent.

Julia Bell is a reader in creative writing at Birkbeck University

Annabelle Hirsch’s new book A History of Women in 101 Objects can be purchased in stores and online, or as an audiobook exclusively from Audible

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments