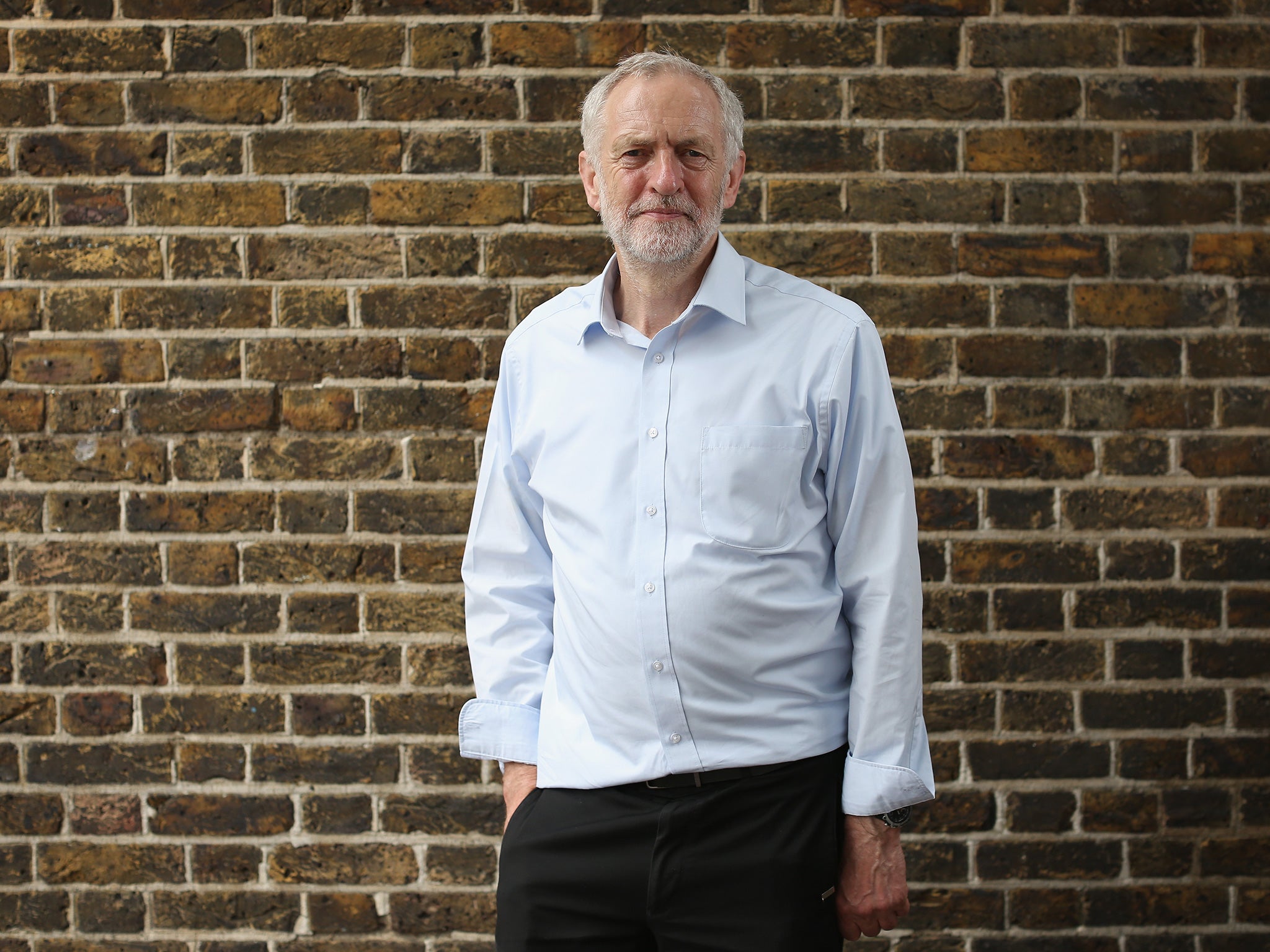

Here's how Jeremy Corbyn engaged Ukip voters without ever uttering a word against immigrants

Corbyn’s unexpected ascent in Britain is striking because it contains none of the divisive language that has been so popular in right-wing politics across Europe

There’s a pattern emerging in international politics. In America, Donald Trump is scaling the polls with the basest rhetoric against Mexicans. Narendra Modi climbed the greasy pole of Indian politics with sectarian appeals for Hindu solidarity. Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the imagery of Arab hordes to galvanise right-wing Jewish voters in Israel’s general elections earlier this year. In Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan continues to hypnotise voters with atavistic spectacles of Ottoman pomp.

The ascendance in Europe of Marine Le Pen and Nigel Farage has triggered a scramble by mainstream politicians to upstage them by usurping their language. After a decade in which Britain and the United States waged wars to promote democracy as a universal panacea, immense chunks of the democratic world – from Asia to North America to Europe – are collapsing into majoritarian self-pity.

Against this dispiriting backdrop, Jeremy Corbyn’s unexpected ascent in Britain is striking because it contains none of the divisive dog-whistles that have elevated politicians in other major democracies to positions of authority. It is impossible, for instance, to imagine Corbyn ever pandering, as Barack Obama so frequently did when he ran for the presidency of the United States, to “traditionalists” by vacillating on the question of gay marriage. Of course, since Obama won two elections and presided over the strengthening of gay rights while in office, Corbyn’s detractors may argue that sophistry and triangulation are imperative to the actualisation of one’s principles.

But such criticisms, echoing Tony Blair’s contention that principle without power is futile, miss the larger point. Corbyn’s campaign is the best advert for participatory democracy in a long time precisely because it is upending our most ingrained assumptions about electioneering. Corbyn is attracting voters to his beliefs not by temporarily concealing or even diluting those beliefs, but by amplifying their relevance and validity. As refugees die and politicians dither, Corbyn's approach stands out.

An Indian diplomat who saw one of Corbyn’s speeches recently told me that Corbyn’s methods remind him of an episode from Gandhi’s life. Gandhi had urged a boycott of Lancashire’s cotton mills because their products were destroying the livelihoods of Indian textile workers. Everyone expected trouble when the Mahatma decided to visit Lancashire in 1931 to speak directly to the mill workers. What greeted Gandhi instead were unanimous cheers from the working classes of Darwen. Racial suspicions that had worked for so long to the benefit of a tiny minority abruptly dissolved. At a public meeting, one of the workers laid off by the local mill owners said, “I am one of the unemployed, but if I was in India I would say the same thing that Mr Gandhi is saying.”

The understated empathy of ordinary Britons, rarely reflected in the deportment of their nation’s overweening ruling elites, is what Gandhi tapped into – and it is what Corbyn is tapping into. Corbyn, the Indian diplomat of my earlier conversation said, “is a keen student of Gandhi. He’s averse to algorithm politics – you input this value, you generate that result. He’s investing in engagement and persuasion.” It sounds simple - but politicians everywhere seem to have forgotten how to do it.

Many of Corbyn’s counterparts in the democratic world cower before – or become pale imitations of – their own versions of Farage and Le Pen. In Britain, Corbyn reaches out to Ukip voters, and he does it without saying an unkind word about minorities or workers from eastern Europe. As demagogues across Europe seek fresh ways to profit from the refugee crisis, Corbyn is demonstrating that it is possible, with a coherent vision, to draw voters away from the dangerous consolations of identity politics.

This would be a tremendous accomplishment even in prosperous times. In an age of severe economic hardship – and in a global democratic landscape studded with such crass majoritarians as Modi, Netanyahu, Trump, Le Pen, and Erdogan – it is a triumph of defiantly inclusive messaging.

British commentators, busy tormenting Corbyn, are neglecting the fact that he is pioneering what is perhaps the most inclusive political movement in recent history. His success at home will do more to advance the cause of participatory democracy and pluralism around the world than any war ever could.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks