Here are some important reasons why the Tories haven't got 2020 sewn up just yet

In the summer of 1992, when the Conservatives had unexpectedly won for the fourth time, the prevailing view was that they would rule more or less for ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In politics, what appears to be happening is almost always the opposite of what is actually happening. The illusion is especially powerful in August, when the rhythms are less familiar than the rest of the year. During these long summer days, the prevailing narrative is that the Government commands the stage and will do so for at least 10 years. Recently, I had a conversation with a Conservative MP – a bright member of the new intake – in which he wondered whether his party might rule for as long as it did after 1979. As a form of confirmation, one commentator tweeted last week that “nobody” believes the Conservatives could lose next time. The entire media focus is on the Labour Party, staging the most extraordinary leadership contest in the history of leadership contests. Any passing references to the Government note only its authoritative dominance.

Perhaps we will look back on this summer as the period in which the Conservative Party acquired a grip on the country as it did after 1979 – but I doubt it. During August 2010, when the Coalition was on its honeymoon and Labour was conducting one of its more soporific leadership contests, we were told that voters loved coalitions, with parties working together for the good of the country. Privately, David Cameron wondered whether he had pulled off a permanent realignment on the centre-right, Cleggite Liberal Democrats dancing happily with Tory radicals. In fact, by that August the seeds of the Coalition’s destruction were sown: tuition fees; the too jolly Cameron/Clegg press conferences; NHS reforms taking shape at the Department of Health. The partnership was already doomed – or at least half of it was – by the time we were all being told that coalitions were here to stay.

In the summer of 1992, when the Conservatives had unexpectedly won for the fourth time, the prevailing view was that they would rule more or less for ever. I was a BBC political correspondent at the time. The BBC is not biased to the left or right, but is biased in favour of whatever is fashionable orthodoxy at the time. There was much talk about how the UK had become similar to Japan: one party ruled and the only significant debate would take place within that party. Yet the seeds of destruction had already been sown. The referendum in Denmark that came out against the Maastricht Treaty in June 1992 had ignited the passions of Tory Euro-sceptics, while the pound was heading for a traumatic exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism. Nothing anywhere near as dramatic is likely to happen in the coming months, but, if we move away from the distorting prism, it is possible to see why the Government is not as mighty as it seems to be.

The collapse of Kids Company last month has wider implications for ministers that seek agencies other than the state to deliver services. No wonder that Oliver Letwin was so keen to keep the emblematic charity alive. For him and others, this is an ideological cause. More practically, for a Government starving local authorities of cash, charities are the great alternative. But when charities, increasingly dependent on Government cash, are forced to close, which institution is expected to step in?

The answer is that local government will have no choice but to intervene. Yet councils are diminished and strapped for cash, too. The collapse of Kids Company highlights the risk of the Government’s favoured multi-agency fragmentation in relation to the delivery of services. Cameron’s “big society” was not dropped after the 2010 election, as some assert. Indeed, the idea was reflected in the rise of Kids Company. But, suddenly, the premise is challenged more fundamentally than at any time. Where is the scrutiny of charities compared with the lines of accountability that keep national and local government on their toes? What will be next? A free school struggling to make ends meet? Another charity?

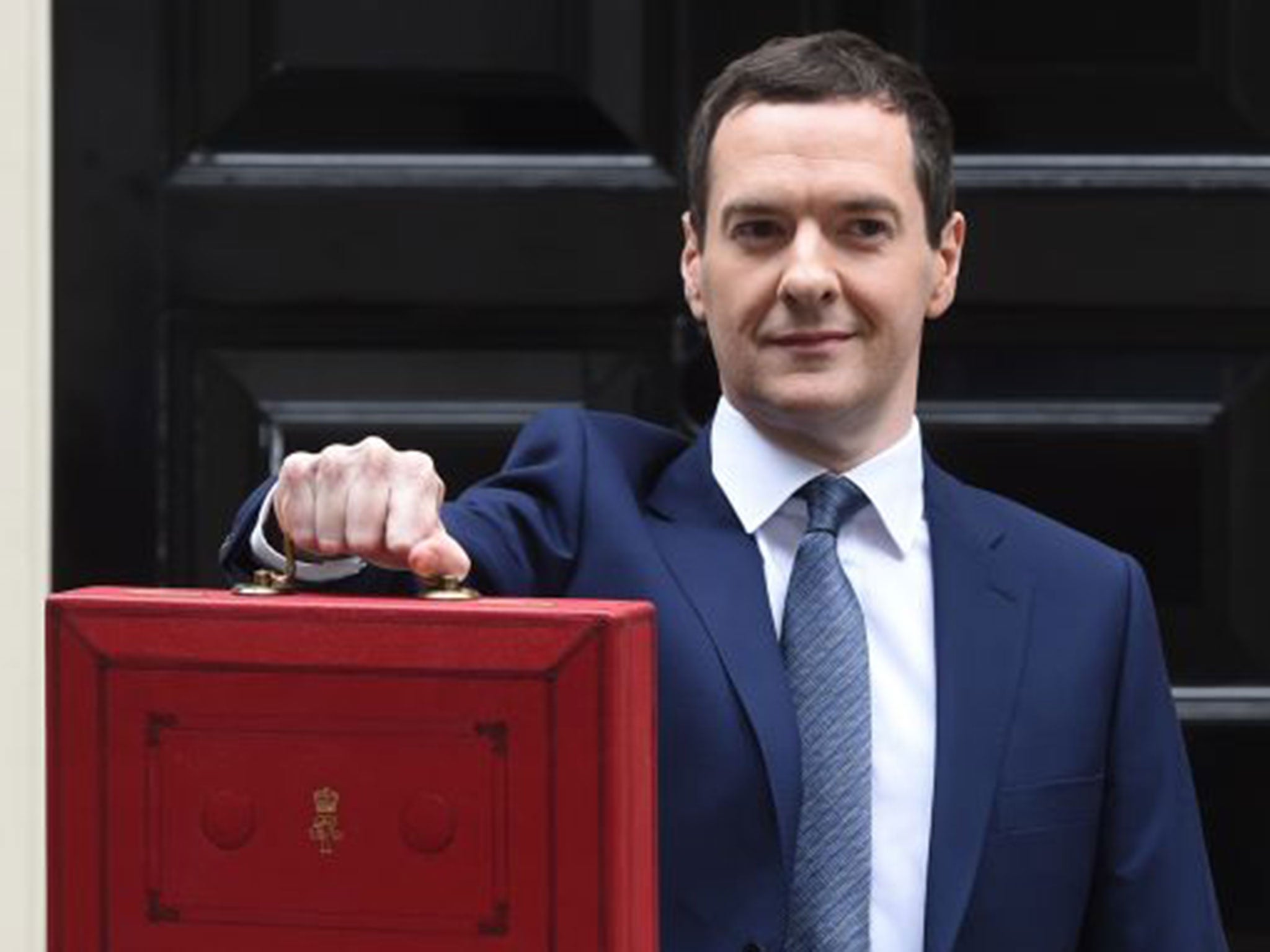

The cuts to come heighten the inevitable risks of fragmented provision. George Osborne’s summer Budget was widely hailed as a titanic masterpiece. As usual, the opposite was closer to the truth. In fairness to Osborne, I should add that the same applied in reverse when we were told that he was a hopeless Chancellor in the months that followed his so-called “omnishambles” Budget in the last Parliament. Once again, the opposite was the truth.

It was around the time that he was meant to be useless that he became sensible, becoming more expedient in his austerity and giving the economy some room to breathe. Now he is hailed as a genius, he returns to his earlier self. The spending cuts are severely testing for a Government with a tiny majority. During the recess, some Conservative MPs have expressed worries about the planned cuts in tax credits for the low paid. In his Budget, Osborne declared that “Britain deserves a pay rise”. Back in their constituencies, Tory MPs are discovering that some of their low-paid voters are getting significant pay cuts. Only a few need to rebel to lose the majority.

The most contentious issue of the lot remains Europe. Several European leaders have indicated that they will block Cameron’s desire to limit the benefit rights of EU migrants. Increasingly, his renegotiation looks as if it will be as minimal as that carried out by Harold Wilson prior to the 1975 referendum. With the political stage to themselves, Conservative MPs will feel freer to demand more, but Cameron will not be able to deliver. After the referendum, the Conservatives’ tricky leadership contest moves into view.

Cameron has more space on the stage than he had dared to hope for before the election. But that stage is still littered with daunting obstacles. There is trouble ahead, and not just for Labour.

Steve Richards is presenting Rock ’n’ Roll Politics at the Assembly Rooms at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe until 30 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments