He was old-fashioned, of course, but Terry Wogan’s voice was the sound of my childhood

Wogan had the measured air of a stoic man suffering the weird world of BBC light entertainment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two wholly different famous people passed away in January, each evoking a similar, highly personal, sense of loss. First David Bowie, a death that led to typically stalwart dad-types shedding heartfelt tears into their cornflakes. Then, this weekend, the death of Terry Wogan, the twinkle-eyed, avuncular king of light entertainment. Wogan: the sound of my mother’s bedside clock radio, which seeped through the house to my bottom bunk, warning us it was time to rise.

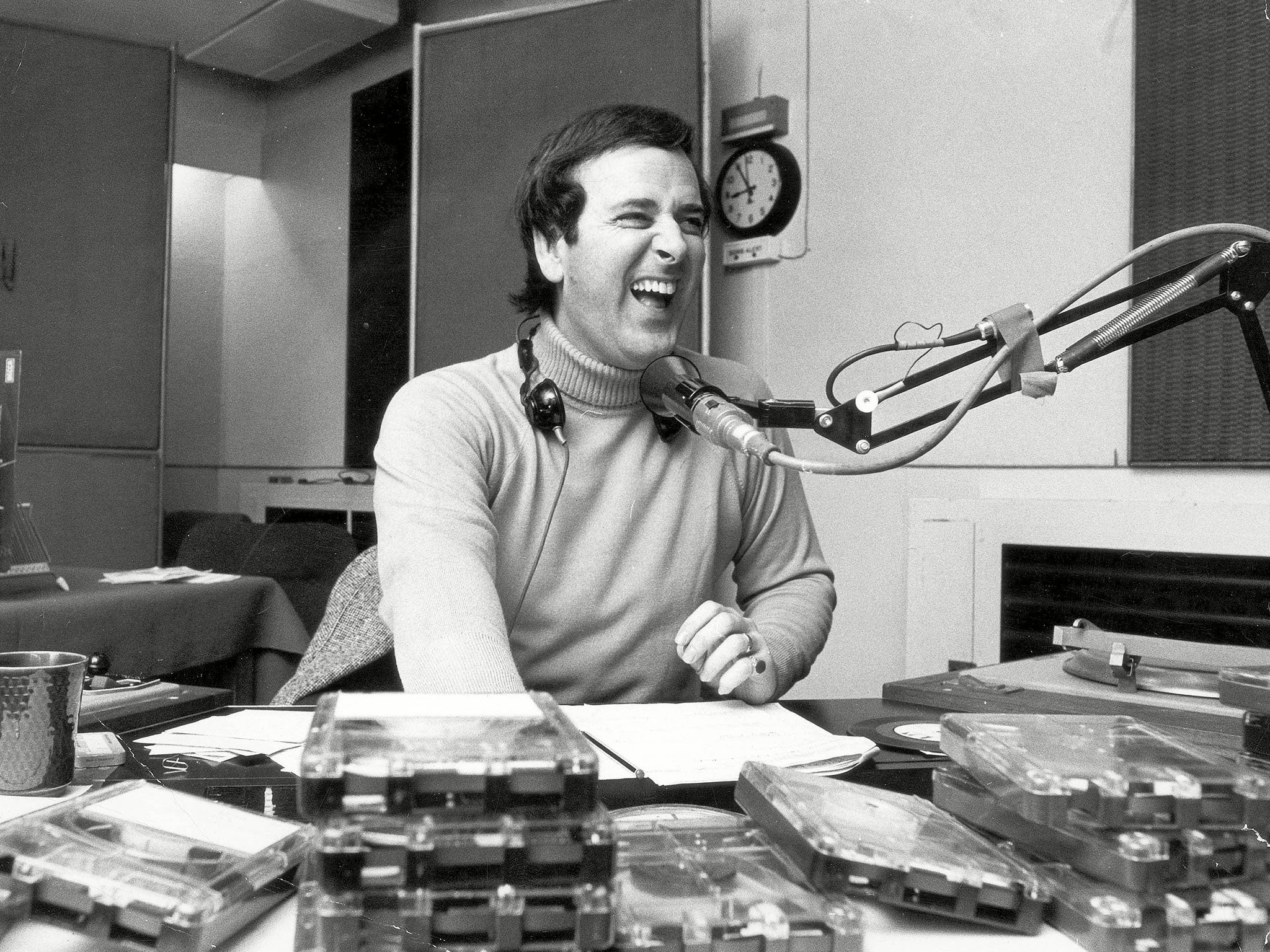

We’d slurp Ready Brek to the sound of Terry playing Don McLean’s “American Pie”, before he would thank a fan for a recently received iced fruit loaf, his voice crackling with barely concealed mischief at the cake’s slapdash frosting and the absurdity of his showbiz existence.

Back then, Terry eased a nation towards their daily duties with a comforting: “We’re all in this together.” His personal touch was so polished that, aged four, I had to be let down gently that this funny, often very silly, man who lived in the box by my mother’s bed was not playing John Denver records solely for us.

But Wogan’s intention was to provide this personalised service. He wanted to feel like a faraway friend. While they lived and breathed, there were few times that David Bowie and Terry Wogan would be found in the same sentence, but now they’ve both gone, I feel a peculiar sense of loss for their era of celebrity. Here were men from a time when life felt greyer and stuffier, who chucked out a joyous lifeline from beyond. They brought a subversive frisson to a drab Seventies landscape. We live, today, in an over-stimulated, click-addicted age, littered with grasping, self-cheerleading famous folk and their sponsored content. Bowie and Wogan were part of a now bygone age of slowness, self-deprecation and sincerity.

But the similarities stop there. For, while Bowie shape-shifted and set many trends over the following decades, Wogan stuck resolutely to his special formula: namely, a nice sweater and slacks, a neatly tamed yet full and sweeping bouffant, and a wry look to the camera during Blankety Blank as if to say: “Look, we all know this is rubbish and the prize is a completely useless chequebook made of stainless steel, but we’ve got Larry Grayson and Windsor Davies here, so let’s make the best of things.”

Wogan always had the beautifully measured air of a stoic man suffering the weird world of BBC light entertainment. He played the role deftly of someone held hostage by his starry fortune. His Eurovision commentaries represented the slow hysteria that sets in after three solid hours of bell-ringing nuns and tone-deaf crooners. Or those indecipherable pre-song mini-films made to “introduce” a country, in which France might be represented by a woman in Pierrot make-up throwing onions in a river. He positioned himself during this televisual marathon as one of us – the bewildered hoi polloi sat at home – rather than a BBC face reading scripted platitudes.

One year, during “Making Your Mind Up”, Wogan announced the wrong British winning entry completely. “Nobody died; it’s a television programme,” he explained with refreshing clarity. During Points of View he managed to communicate – via a millimetre of northwards eyebrow – that he too agreed that “Disgusted of Dudley” probably needed a little more fresh air.

Wogan stayed within the BBC, cocking a respectful snook at its sacred cows, for 40 years. That, alone, is a remarkable feat.

And, though Wogan’s chat show didn’t have the cerebral thrust of David Frost’s – or, frankly, even Russell Harty’s – it was a reliable three-nights-a-week delve into the modern celebrity landscape. The clips that remain are a far cry from the publicity junket by-product of modern shows.

Deaths like these feel so emotive because they force us to glance backwards to what is gone, and then to check where it is we’re heading. What was especially remarkable (perhaps pleasing) about the modern legend of Terry Wogan was how younger generations of broadcasters looked up to him. They thrilled and squeaked with pride if he ever commented on their shows.

He never attempted to be edgy, or experimental, in order to keep his celebrity flame ablaze. Wogan wasn’t a yesteryear Kanye West, incessantly self-identifying as a trailblazer, a mentor or a Svengali. He didn’t demand respect.

Wogan’s biggest stab at reinvention was a recent TV show in which he broke free of the studio and went to places like Scunthorpe in a black taxi. But still, be it 1980 or 2015, he was always simply 100 per cent Terry Wogan. He revelled in old-fashionedness and shame-free fuddy-duddyness. He stuck to what worked for him, and thus his star quality was seemingly unquashable. He inspired broadcasters to be excellent rather than wackily ever-evolving.

Not many BBC stars provoked the reaction Wogan did from staff as they walked around Broadcasting House. I’ll confess that my knees slightly buckled on one of the few occasions I saw him. It felt like I’d bumped into the ghost of school mornings past. There was a peculiar urge to cuddle him.

I’m sure he got this reaction all the time; it must have been exhausting. At least he knew how much he was loved when he was living. We didn’t speak up too late.

There are a million things to distract me each day before breakfast in our exciting modern entertainment landscape. Each time a great like Bowie or Wogan dies, I feel that less was often more.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments