Like Hasan Minhaj, I exaggerate funny stories for effect – who doesn’t?

Should a stand-up be held to account for fabricating elements of the stories they tell on stage? Comedian Vix Leyton explains why embellishing anecdotes is just a part of human nature

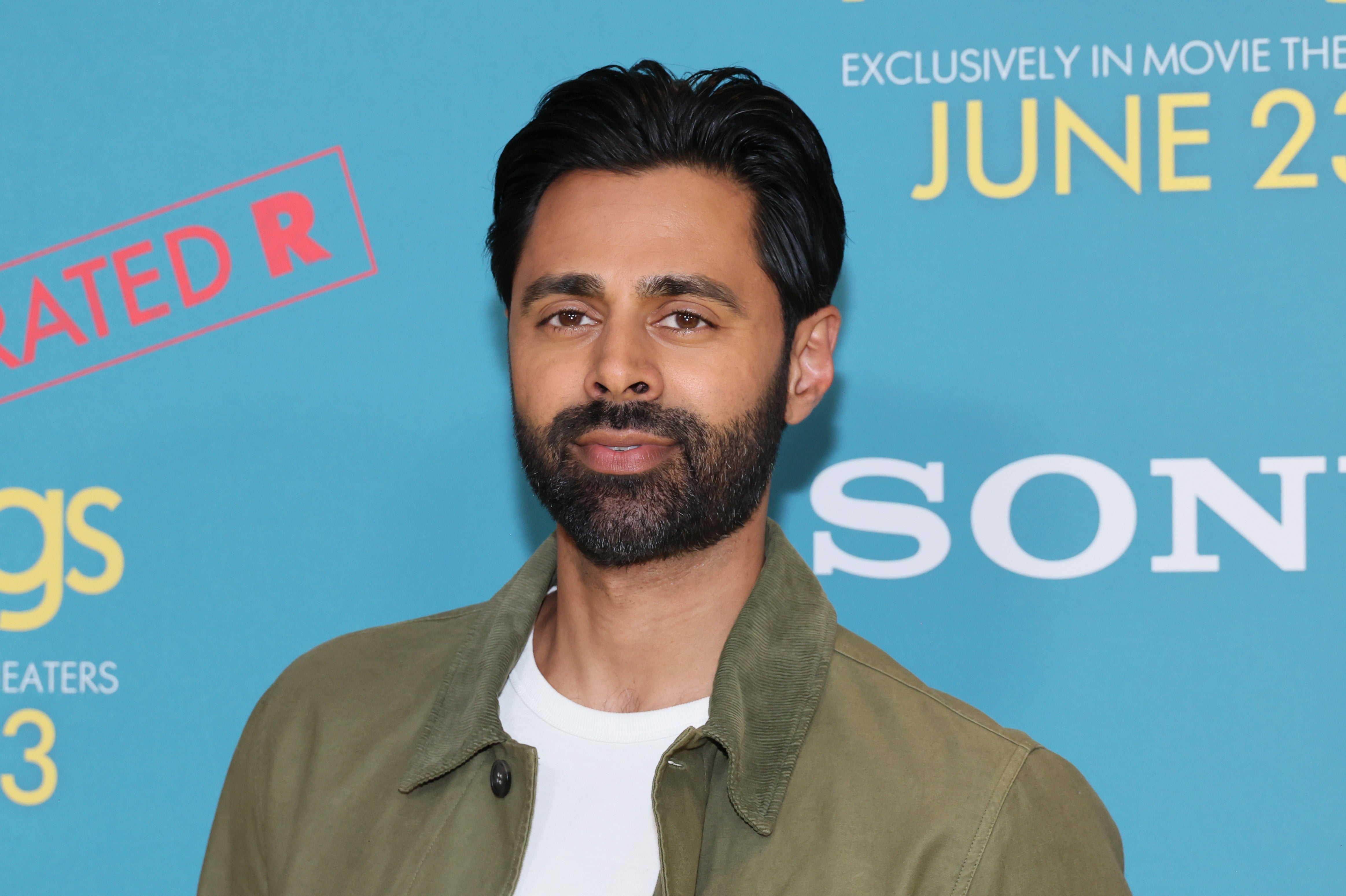

The notion of comedian Hasan Minhaj being exposed for exaggerating stories in his stand-up set seemed laughable when I initially saw the story a couple of weeks ago. Slow news day, I mused; yet weirdly this still hasn’t gone away. Weeks later, it’s still rumbling, to the point he had to issue a 20-minute video to rebut claims he used “fake racism” to advance his career.

But did he actually do anything wrong? To me, a fellow comedian, it feels like this need to hold jokes, stories and anecdotes to account can only be attributed to the savage social media-fulled need to stir up outrage, as if we don’t already have enough to be furious about.

We are undoubtedly living an era of increasingly blurred lines between what is news, what is opinion and what is entertaining “constructed reality”. It is a world where Big Brother, Love Island, TOWIE, Married at First Sight and a litany of other shows are “secretly” scripted for drama, TV and clickbait headlines. But we all know that – don’t we? So, what’s the problem?

Yet you can’t seem to throw a stone on X (the artist formerly known as Twitter) nowadays without seeing a creatively massaged mediocre situation quickly turn into a 180 character opportunity for “likes” and engagements: Laurence Fox’s taxi driver allegedly congratulating him on sticking to his principles; the woman who got a round of applause in the voting booth by audibly looking for the Tory box; that mate of yours torn down for boasting that their three-year-old has a snappy solution for the economic situation in Greece.

I just don’t know why people are so het up by it all, when there is more space than ever for a sprinkling of exaggeration to elevate the humdrum – it helps the day pass more quickly, if nothing else. And it’s by no means a new phenomenon. We all have that one mate who tells tall tales down the pub – the adult equivalent of Jay from The Inbetweeners, the one who has a girlfriend who “goes to another school”.

Amplified reality is a stock in trade of making the monotony of living a little more sparkling – a way to make yourself feel a little bit like the main character. And I would argue: what’s so wrong with that?

In real life, when it happens, I laugh along anyway. On social media, I’ll often “like” something that I suspect isn’t a verbatim account, simple because it made me smile. Yet beneath my supportive “heart” or “LOL” there will always be a cynic, flagging someone’s tweet to the “Didn’t happen of the year award” (DHOTYA) account even when it’s a claim as innocuous as getting two chocolates out of a vending machine at work, when you paid for one.

Do we really need these “truthers” of everyday exaggeration? What purpose does it serve to police people’s little white lies?

Ed Byrne’s latest show – dealing with the death of his brother – is titled Tragedy plus Time. It’s based on the notion that comedy equals tragedy plus time: time to process it, time to find the dark laughs and the moments of levity that got you out of bed when everything felt impossible. British people are arguably world champions for that type of gallows humour.

Ultimately, that is what some of the best stand-up comedy is. You see real craftspeople in comedy taking everyday horrors – a spell in hospital eating the awful hospital food, or the time someone waggled the handle of a public toilet cubicle you were in – and making it hilarious.

There is nothing better than a shared moment of connection with another human being where you realise with delight that you have had a similar experience. We all want to be the person telling the story that gets the whole pub table laughing.

And we all have things happen to us that we can’t wait to relay to others. Often, in the midst of a disaster, you think “I’ll laugh about this – not today, but I will”.

It’s a skill to turn these moments into comedy gold, and with limited stage time you often have to edit hard to get to the crux of the point without going round the houses, or tweak the biographical details to pump up the drama for a bigger punchline pay off. On stage, it’s normal to sprinkle small “observational” laughs throughout to get you to the big finish. Phone calls become real life meetings, where you can mine body language and descriptions of locations; real people become cartoon caricatures.

Some comics stay close to the truth (and close to the bone) with just a few creative flourishes, and others make things up entirely. I know happily married comics who talk about dating like they’re living their best life on Tinder, because that is what people want to hear (being content and in love is pretty fallow for laughs, and probably less relatable).

Comedians also vary in terms of how much of themselves they share. Unlike journalists, we are not obliged to give 100 per cent accurate accounts of our lived experience on stage. But I can see where the confusion comes from.

Parasocial relationships created by unprecedented modern access has confused people’s expectations a little bit, with comics spending hundreds of hours talking on podcasts, sharing “content” and tweeting pithy side notes into the digital ether. It is understandable that fans feel like they know them and might feel betrayed to be “misled” by an exaggerated anecdote.

The trends in popular comedy have also changed, sometimes demanding a higher level of intimacy. It is no longer quite as respected to be just funny “for funny’s sake”. Critics now demand that we create comedy that also makes you feel things – that make you laugh, cry and learn. It is amazing when comedy hits all those markers, but it shouldn’t have to – and there shouldn’t be an obligation to report situations accurately at the expense of being funny.

We’ve come a long way since club comedy focused on the perils of your mother-in-law coming to stay, but despite those tropes falling out of fashion, the jokes still work, because there is a grain of shared experience to them.

Ultimately, a comedian’s job on stage is not to tell the truth, it’s to get a laugh – and we should be able to trust that the audience is in on the joke.

Vix Leyton is a Welsh stand-up comic

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks