Why Halloween can be like therapy for some people

Nobody would choose to walk home through a dangerous neighbourhood after watching a slasher movie. We seem to want to be scared, but we want to be safely scared

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is fascinating and paradoxical how we spend a great deal of time understandably avoiding those things that frighten us…and a great deal of time deliberately flirting with them.

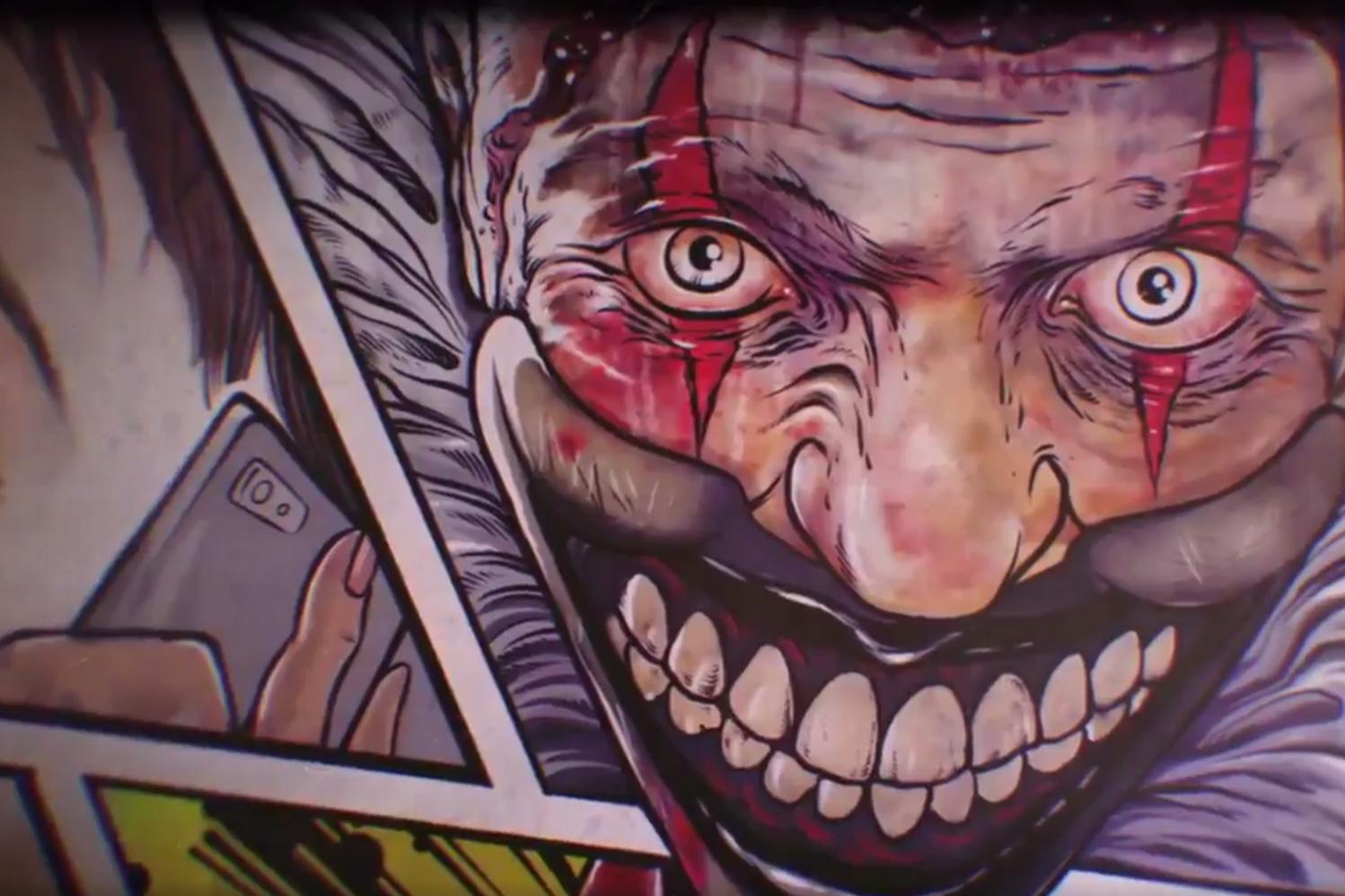

Halloween is a perfect example of this; we thrill ourselves playing with monsters, daemons, death and horror. But we see the same phenomenon elsewhere. Scary movies are hugely popular all year round and we flock to theme parks in the summer in order to terrify ourselves with gravity-defying rides.

When we look at these phenomena in detail, they look rather odd. Nobody would choose to walk home through a dangerous neighbourhood after watching a slasher movie. We tend to choose terrifying, gravity-defying, roller-coasters, but most of us would absolutely refuse to get on a ride that had recently failed a council safety test. We seem to want to be scared, but we want to be safely scared.

This paradox most likely results from our need to learn how to master our anxiety. Although I am uncomfortable with the flagrant commercialisation of the American version of Halloween, it offers us a chance to help our children manage anxiety – literally to laugh at their fears.

Children (and adults) have a lot to be fearful of. Quite apart from the fact that we are all going to die (an inescapable fact, but nevertheless an issue that we all seem to try to avoid thinking about), we live in a world of a nuclear-tipped North Korea, climate change, asymmetric terrorist warfare, and nationalists, misogynists and criminals in high political office. We all need to learn how to confront our nightmares.

How we learn to control our fears has been the subject of academic study. My colleague Sara Tai, at the University of Manchester, has looked closely at how we learn to appraise and control our anxieties. In a particularly Halloween-related study, Sara, Andrew Healey and Warren Mansell found that if they allowed people to “play” with spider imagery (rather than trying to “cure” their “arachnophobia”) their anxieties lessened.

A common therapy for anxiety involves “exposure”, when people are encouraged to approach the things they fear, and therefore to learn to master their anxiety. But, of course, most of us avoid those things that scare us. That means the process of therapy can be very difficult for many people.

What my colleagues in Manchester found was that when people had greater control over the situation, and could “play” with their anxieties, they were more able to approach the problem (in this case the scary spiders), were less likely to use avoidance as a coping mechanism, and so were more able to make therapeutic progress.

If we didn’t have a way of managing anxiety in our imagination, we would be floored by it every time it came up for real. We play with these ideas a little like a kitten plays with a ball of string – preparing ourselves for challenges we might face later.

We learn to manage anxiety, we learn to control our fears, we learn what are the safe and acceptable parameters, we learn how to talk to each other about our fears. This is not incompatible with the fact that anxiety is also a serious mental health problem; it’s part of our mechanism for dealing with it.

Who knows...if we embrace the messages of Halloween, if our children confidently play with these ideas, and learn to control their fear of the ghouls, the dragons, the wizards, then maybe they’ll grow up with the courage and wisdom to vote the real monsters out of office.

Peter Kinderman is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Liverpool

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments