Further thoughts about referendums

The referendum is not such a new-fangled constitutional innovation after all, and it was the right way to decide the fundamental question of our EU membership

Thanks to the many people who have commented on my posts about whether, in principle, we should have referendums in Britain. Some assumed from the headline, “Should referendums be banned?” that my answer is Yes, but they should have known from my fondness for QTWTAIN (Questions To Which The Answer Is No) that it wasn’t.

I am in favour of referendums on fundamental questions, such as the passing of power from the House of Commons downwards to nations, regions or cities, or upwards to the European Union. I think the EU has changed in the 41 years since the British people last approved our membership, and that it was right to ask us again. I do not think the timing of this referendum made much sense, but it was probably overdue rather than too early.

In hindsight, David Cameron locked himself into a tight timetable with his 2013 promise of a referendum “within the first half of the next parliament”. I know why he restricted himself in that way: he didn’t want the wrangling over Europe to dominate the whole of his second term. If he had given himself the flexibility to hold the referendum late in the parliament – just before he stepped down in 2019, say – I don’t think he would have made use of it. The plan was always a quick renegotiation and a dash to the polls. Nor, I think, would holding the referendum three years later have produced either a more substantial renegotiation or a different result.

Personally, I was a reluctant Remainer, but I am quite happy with the result and don’t agree with attempts to reverse it. In these I am surprised to find myself aligned with Jeremy Corbyn.

The biggest disagreement with my thesis came from Will Cooling, who thought that, if there had been no referendum in this parliament, the popular majority for Brexit would have been eroded by demography. He thought that, as new young Remainers came onto the electoral register and older Leavers died off, the Remainers would have become the majority within a few years.

I am not so sure. I don’t think EU membership is something that we as a nation were getting used to. For some time, opinion has been moving away from EU membership. It may be that, as people get older, they became more likely to support Leave.

Where Will is certainly right is in thinking that, if the decision had been postponed, Brexit would have been less likely. Who knows what will happen over the next decade? Angela Merkel will not be German chancellor for ever. Other countries might rebel against the free movement of people, allowing member states generally to impose the kind of restrictions that Ms Merkel wouldn’t allow Mr Cameron to have in his renegotiation. But that would simply be achieving much of Brexit by other means.

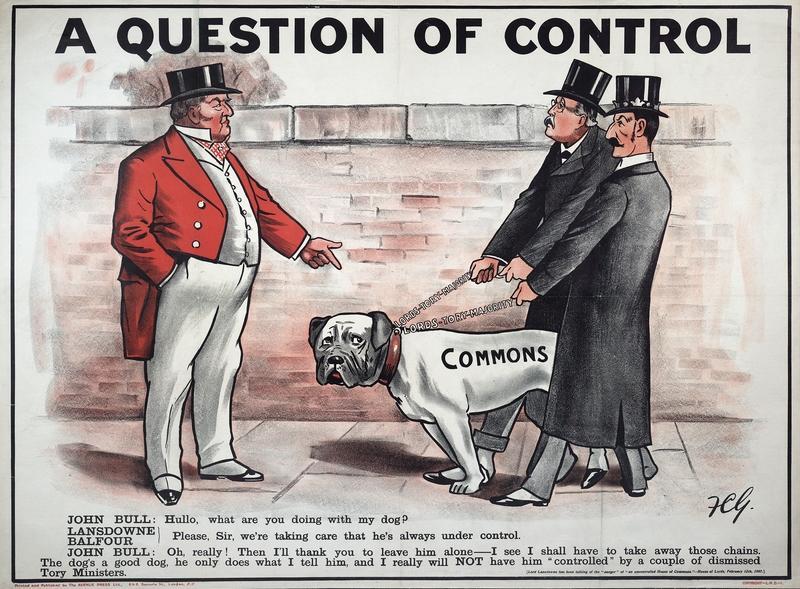

What I did not know was that the referendum was not a completely new idea in the 1970s. I am grateful to Mr Memory for telling me that Arthur Balfour, the Tory former prime minister, had advocated a referendum in 1910 as a way to hold his party together over tariff reform. Indeed, I had no idea that Professor Vernon Bogdanor had written a book on the subject, The People and the Party System: The Referendum and Electoral Reform in British Politics, 1981, which starts with a section entitled, “The referendum, 1890-1980”. Prof Bogdanor explains how AV Dicey, the constitutional theorist, was in favour of referendums in the 1890s as a way to restrain the growing power of the House of Commons, given the problems of the House of Lords trying to do so in the name of the people.

The idea was taken up by Mr Balfour when the Lords and the Commons clashed in 1909 over the “People’s Budget”, and the Liberals went to the country to secure a mandate for it. In Mr Balfour’s election address, the equivalent of the Conservative party’s manifesto, for the January 1910 election, he said: “If you ask me whether this constitutional machinery could not be improved, either by some change in the composition of the House of Lords, or by the institution of a referendum, I am certainly not going even to suggest a negative reply.” Deciphering the double negative, Mr Balfour was suggesting a referendum as a possible resolution of the conflict between Commons and Lords.

The Tories gained seats, but failed to dislodge H H Asquith’s Liberal government, and Mr Balfour made no mention of the idea in his address at the second election that year (which produced the same result).

Thanks also to Rich Greenhill for reminding me that local referendums, meanwhile, were adopted in the Temperance (Scotland) Act 1913. Hundreds of referendums were held in the 1920s to decide, at local council ward level, whether residents wanted their area to be “dry” – only about 40 did.

The idea of the referendum, therefore, predated the extension of the franchise to un-propertied men and to women. But it wasn’t until Harold Wilson, as leader of the opposition, adopted the policy in the summer of 1972 – to the disgust of Roy Jenkins, who resigned from the shadow cabinet in protest – that the national referendum finally became part of the British constitution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks