EU referendum: Here are three good reasons why the Out campaign might win

If you look at all the polls, 28 have put Remain ahead and 10 have put Leave ahead

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Having rashly predicted that the British people will vote to stay in the European Union, probably on 23 June, I ought to test the arguments for thinking that they might go the other way. There are three important ones.

One is that the deal falls short of what the Prime Minister promised in the Conservative manifesto. He said new arrivals from elsewhere in the EU would have to pay taxes here for four years before they could claim in-work benefits, such as tax credits. The offer from Donald Tusk, the EU President, is that new workers would become gradually entitled to benefits over four years.

Nor is even that guaranteed. It turns out that it requires the European Parliament to pass the legislation. Martin Schulz, President of the Parliament and a member of the socialist group of MEPs, was in London on Friday sounding oddly unhelpful about it.

If David Cameron cannot come up with a better deal on this point at the summit at the weekend after next, the “Remain in the EU” campaign will feel as if it is driving with the emergency brakes on.

But I notice a change in what the Prime Minister’s people are saying. Before Tusk’s documents were published, they insisted that his text would “not be definitive” and “people would work on that”. And after the national leaders started talking to each other – as Cameron was doing at the Syria donors’ conference on Thursday and in Poland and Denmark on Friday – everything could be reopened, I was told. Since the documents were published, however, the Downing Street line has been that they were “significant things” and that the Prime Minister was proud of having achieved so much.

The Tusk deal also falls short of another Conservative manifesto promise: “If an EU migrant’s child is living abroad, then they should receive no child benefit.” Cameron now accepts that child benefit should be paid, but at the rate applying in the child’s home country. “It’s being set at Bulgarian levels,” says an adviser, dismissively. This is sensible – to cut off child benefit completely would increase the incentive for workers to bring their children into the UK – but the Leave campaigns will present it as a sellout.

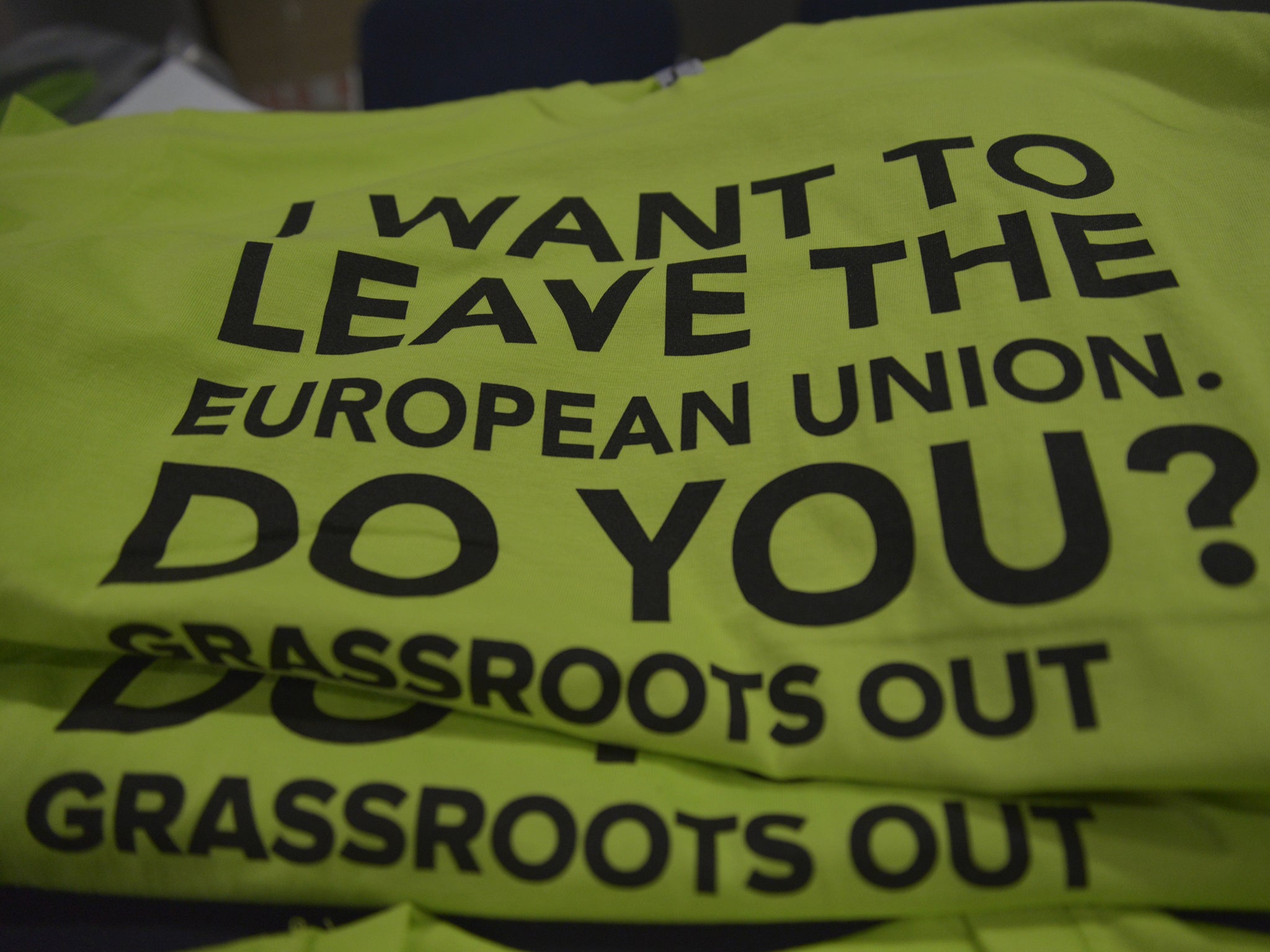

The second reason for thinking that people might vote to leave the EU is the anti-establishment mood that is supposedly sweeping the world from Podemos to Bernie Sanders via Syriza and Jeremy Corbyn. Philip Collins in The Times thinks the conditions are “gathering for the possibility of a debate that is not In versus Out, but Us versus Them”. I got Corbyn’s leadership election wrong, so I have to be careful, but internal party elections are different from referendums of a whole nation.

The British electorate is negative about politics and resentful about the EU, so I can see what Collins means. But I think we would have seen more evidence of support for Leave in the opinion polls by now.

This might seem odd, because of the attention paid to last week’s YouGov poll, the first to be carried out after the draft deal was published, which showed Leave 12 points ahead (if you exclude don’t knows, as you should). But if you look at all the polls carried out since the revised wording of the referendum question was announced in September, 28 have put Remain ahead and 10 have put Leave ahead. What is more, internet polls such as YouGov’s tend to produce better figures for Leave than phone polls, so because there are more internet polls, that summary flatters Leave.

Which leads to the third reason for doubting that Remain can win, which is that the opinion polls could be wrong. There are middle-class Outers, such as Tom Harris, who wouldn’t dream of expressing such a view in public because it is not respectable. There was a lot of talk about “shy Tories” skewing the polls before the general election, which ended rather inconclusively, but I think the stigma among right-thinking people of voting with Nigel Farage, Iain Duncan Smith and Chris Grayling is greater than that of voting for David Cameron.

So it is possible that the polls understate support for Leave. Even so, the bigger lesson of the general election was that polls are not a substitute for judgement. At this stage, they may not tell us much: people know Europe is important and that they ought to have an opinion, but they haven’t given it a great deal of thought. The most notable finding in YouGov last week was that, after voters were asked about various elements of Cameron’s deal, the lead for Leave narrowed from 12 points to four.

Just as, last May, the fundamentals were in the Prime Minister’s favour, so they are in this choice. Leave has no leaders and voting for change is a risk. I think it would take something big to go wrong for Cameron to lose.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments