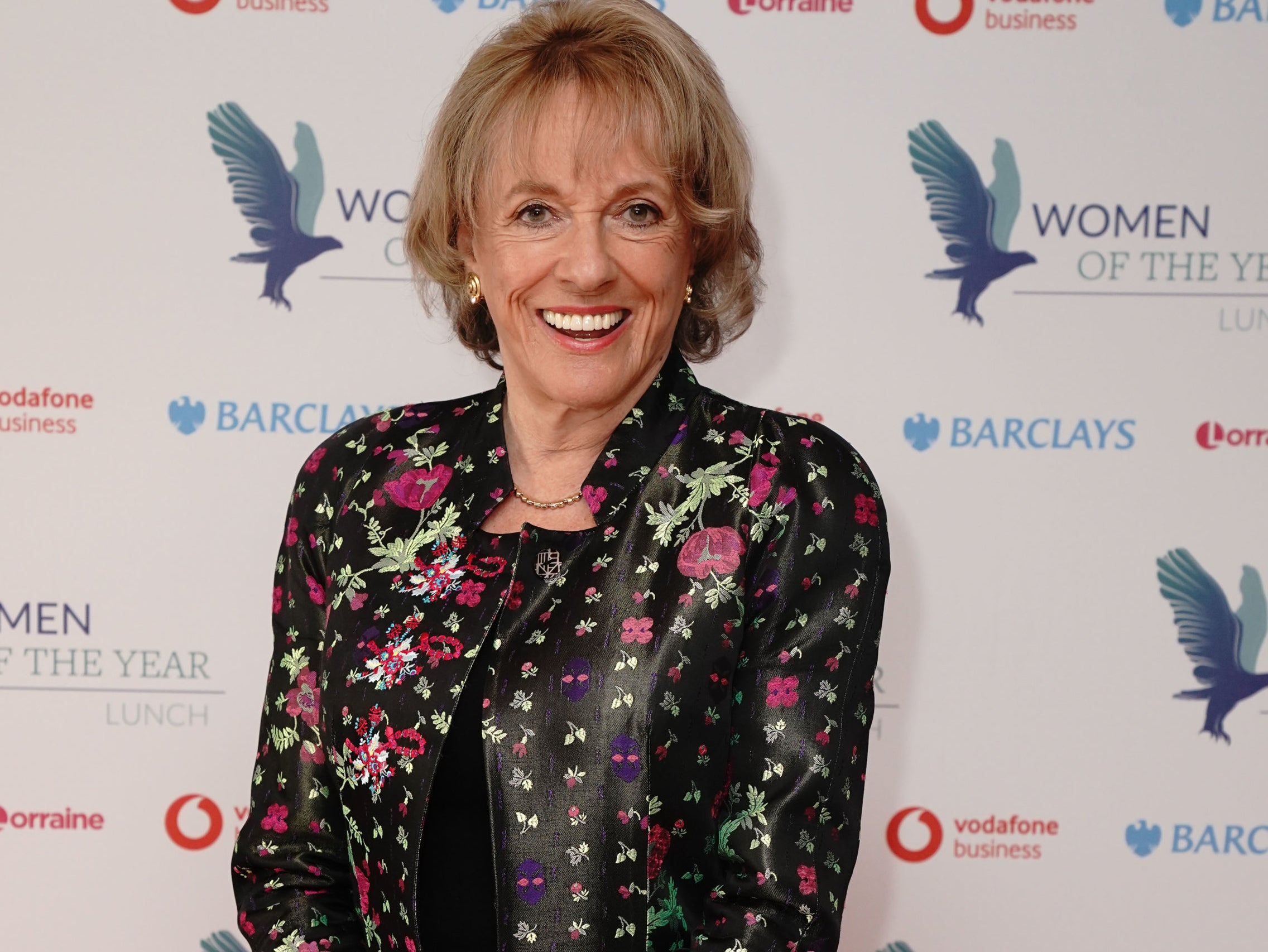

Like Esther Rantzen, I want to decide when and how I die

I am not scared to die, writes Dr Stephen Duckworth, who was paralysed in a rugby accident aged 20. It is time the UK changed its cruel and outdated legislation and gave people rights over their own death

The opportunity to celebrate our life, to say goodbye to the people we love, and to slip away peacefully on our own terms, avoiding unnecessary pain and suffering – is that not how all of us would want to go?

Dame Esther Rantzen has vividly pointed out how this is not possible under our current legal process. She has terminal cancer and previously sad: "I have joined Dignitas. I have thought, well, if the next scan says nothing’s working I might buzz off to Zurich – but it puts my family and friends in a difficult position because they would want to go with me.”

Currently, for those few Brits who can afford the £15,000 price tag, there is Switzerland-based assisted dying organisation Dignitas – but this involves travelling to a foreign country, and often dying before they are ready because airlines require individuals to be fit to travel.

The current law contains far more risks for potentially vulnerable and dying people. The reality is that prohibiting assisted dying does not make it go away and there are currently no workable safeguards to protect dying people. It simply forces dying people to suffer against their wishes or resort to unimaginable actions to control their deaths – often in secret, without the possibility of open conversation or exploration of other potentially beneficial options.

For those without the funds, some may be able to refuse treatment that is keeping them alive and be sedated while their disease consumes them, or while they starve or suffocate. But this can involve a drawn-out death, with no guarantee that suffering can be relieved, and it is not an option for all illnesses.

The only choice remaining is to take matters into their own hands. These deaths are often violent and painful, can involve multiple attempts, and cause untold devastation to those left behind. Imagine resorting to drinking three litres of bleach and taking 10 days to die; a case that has stuck in my mind since I sat on the Commission on Assisted Dying a decade ago.

Fortunately, more and more parliamentarians are waking up to what the assisted dying ban really means. Many MPs and peers of all parties are now calling for a review of our cruel and outdated legislation.

Andrew Mitchell, MP and minister of state for development and Africa, said, “I was so adamantly opposed to assisted dying until I heard stories from so many of my constituents. Often with tears pouring down their faces, they have given me deeply intimate details of the last days of someone they loved but who died a miserable and sometimes very painful death. I have changed my mind.”

MPs need to fully understand how the current law is operating if they are to make informed decisions about what is right for our country and citizens. That includes understanding the views of diverse groups – most importantly dying people and their loved ones, but also healthcare professionals, the police and disabled people.

Personal choice, autonomy and control are values that all people hold dear, and it is no surprise to me that the vast majority believe that people nearing the end of their lives should be able to exercise those rights over their death. But this fact does not appear to be well known among parliamentarians.

I am not terminally ill, but one day I may be. I am not scared to die but Rantzen and most of the population want choice and control over how they manage that dying process.

While more than 206 million people live in places with some form of legislation that enables assistance to die, it is not an option in this country. The UK upholds a blanket ban on assisted dying, despite 84 per cent of the public supporting this option being made available for terminally ill Brits.

I know that transparent, safeguarded assisted dying legislation and protections for disabled people can co-exist and work effectively, and there is international evidence to prove it. In Oregon, for instance, a tightly restricted assisted dying law has been in place for more than 25 years.

Other jurisdictions around the world have had a civil, thorough debate, examined the evidence, and concluded that changing the law on assisted dying is the right thing to do. The UK is increasingly the outlier.

With momentum building around the world and at home, it is inevitable that before long an assisted dying bill will be brought before parliament again. MPs must be fully informed on the reality of the current law, on potential models for change, and on the views of their diverse constituents – the majority of whom, want to see the UK become the latest country to legislate for assisted dying.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks