With Vauxhall’s Luton factory facing closure, the government must urgently rethink EV rules

Consumers aren’t buying electric and this is not the manufacturers’ fault. Business secretary Jonathan Reynolds has been commendably quick to launch a review. Now, he must follow through, writes James Moore

Britain’s electric vehicle problem can be best summed up by an old saying: “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.”

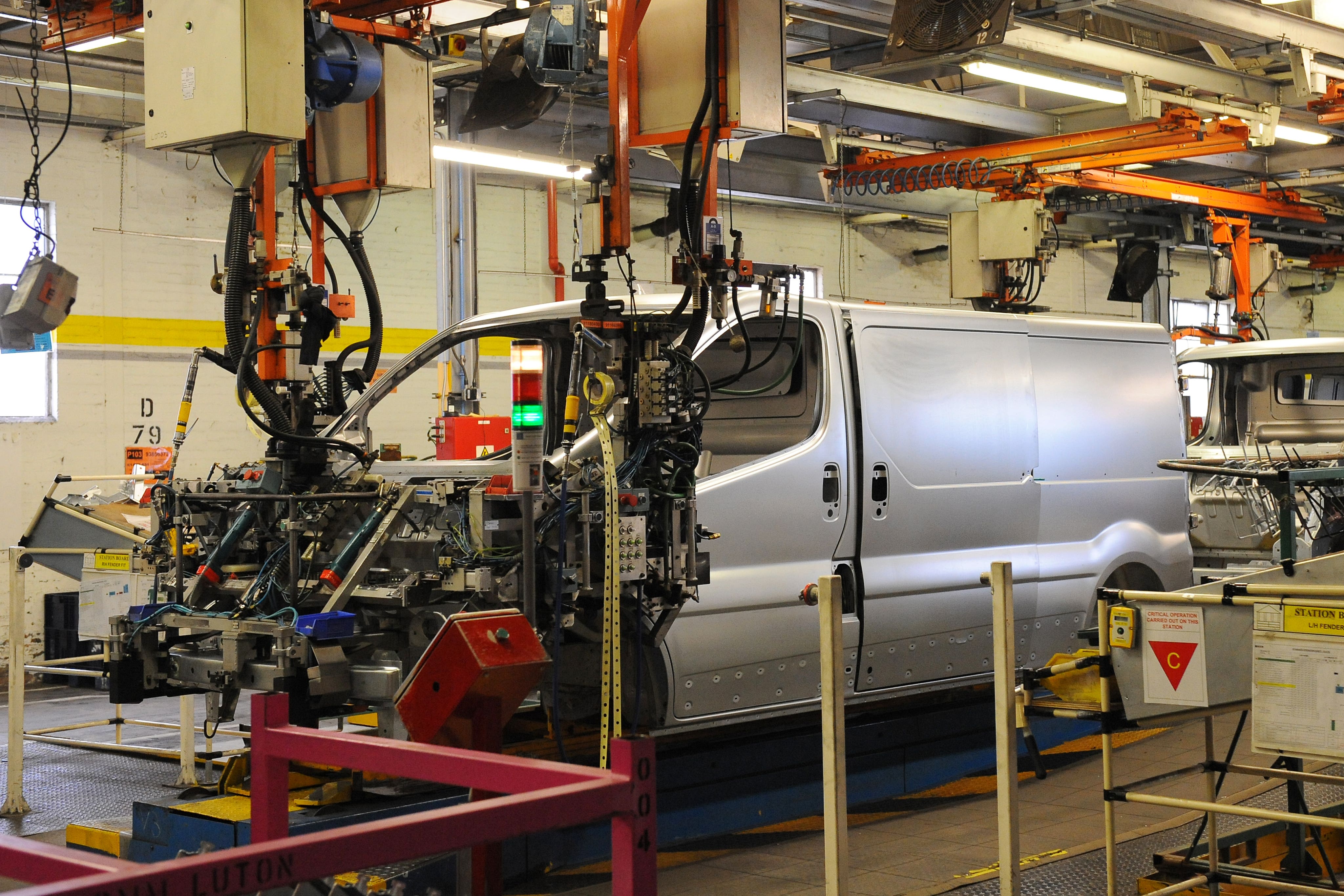

Stellantis, the multinational motor manufacturer which owns Vauxhall, said the UK’s tough electric vehicle (EV) mandates – setting quotas for manufacturers’ EV sales enforced by financial penalties – were partly responsible for its announcement of plans to close its Luton van-making factory. The move will deal a devastating blow to the town with 1,100 jobs under threat,

The announcement ignited a fierce debate, with the Society of Motor Manufacturers claiming the UK’s rules will cost the industry £6bn in 2024 alone. This is, needless to say, unsustainable from a financial perspective.

When the UK’s transition mandates were unveiled, they didn’t look likely to cause any problems. The industry anticipated that 457,000 electric cars would be registered this year alone. That would have accounted for 23.3 per cent of total sales, comfortably above what the quota called for. However, the latest projections suggest there will be 94,000 fewer registrations, with a total of 363,000, a market share of 18.7 per cent.

It’s even worse with vans. Just 20,000 are set to be registered this year, half the expected number. That accounts for a market share of only 5.7 per cent against this year’s target of 10 per cent. Consumers aren’t drinking, partly because EVs are relatively expensive and partly because of concerns about charging (even when there are charge points available they are often unnecessarily complicated to use).

Manufacturers have thus been forced to subsidise sales via incentives. Of that £6bn, the society says £4bn comes from discounts. Generous though they may be, they aren’t working, triggering a potential £1.8bn in compliance costs, which will either go to the government or competitors. This is where it gets perverse. Quota points can be purchased from the likes of Tesla or the Chinese manufacturers, which are, obviously, fully electric. This subsidises the sales of the latter even though none of them have a manufacturing presence on these shores.

The UK kicked its domestic industry in the teeth once via Brexit. Government policy is now doing it again. To coin another old saying, it is cutting off its nose to spite the motor industry’s face.

True, this is not the only country forcing a transition. The EU is doing it. But a ban on new petrol or diesel-fuelled vehicles will not happen in Europe until 2035, against 2030 for the UK, with a checkpoint calling for new car CO2 emissions to be 55 per cent lower from 2030, vs 2021 levels, but without the same penalties.

California imposes zero-emission vehicle mandates, with quotas similar to those in the UK. Its standards have also been adopted by several other (Democrat-controlled) states along with Washington DC.

However, its cut-off also doesn’t take effect until 2035 and, significantly, it also classes plug-in hybrids as “zero emission”, which the UK does not. Hybrids have proved to be quite popular with consumers as a halfway house without the (perceived) drawbacks of going fully electric.

Now, I support efforts to decarbonise transport and not just because it is a necessary step if we are to reduce the malign impact of global heating. It is often forgotten that it isn’t just carbon that petrol and diesel-engined vehicles cough up. They contribute greatly to the UK’s poor urban air quality. This damages the health of children and those with respiratory conditions in particular, but we would all benefit from clearer air.

However, the EV transition and the rules designed to encourage greater take-up are clearly not working as intended and I don’t believe manufacturers are at fault. They have pumped billions into the construction and marketing of EVs, both in the UK and globally, including in places where there are no mandates, such as in red states in the US. The commercial breaks during NFL games are stuffed full of ads for electric vehicles.

Penalising them for failing to meet quotas is not working, and it may be threatening the viability of the UK industry. It should be pointed out that the rules were introduced by the previous Tory government and were well-intentioned. But – sorry, cliche No 3 coming – the road to hell is paved with those.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves, meanwhile, didn’t do anything to help. On the contrary. Her decision to maintain the freeze on fuel duty was another example of the government working against its own stated aims through the tax system, the most obvious example of which was taxing jobs by raising employer national insurance.

Business secretary Jonathan Reynolds is to be commended for setting up a super-fast consultation on the mandates. But a super-fast response is now needed. Over the longer term, the government also needs to look carefully at EV policy and ways to incentivise greater take-up.

Combating climate change is a fight we must win. But public support is required to do that and it will leach away if job losses and empty factories are the end result of green policies. Reynolds must act to prevent any more of those.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks