My family and the mystique of the 1922 Committee

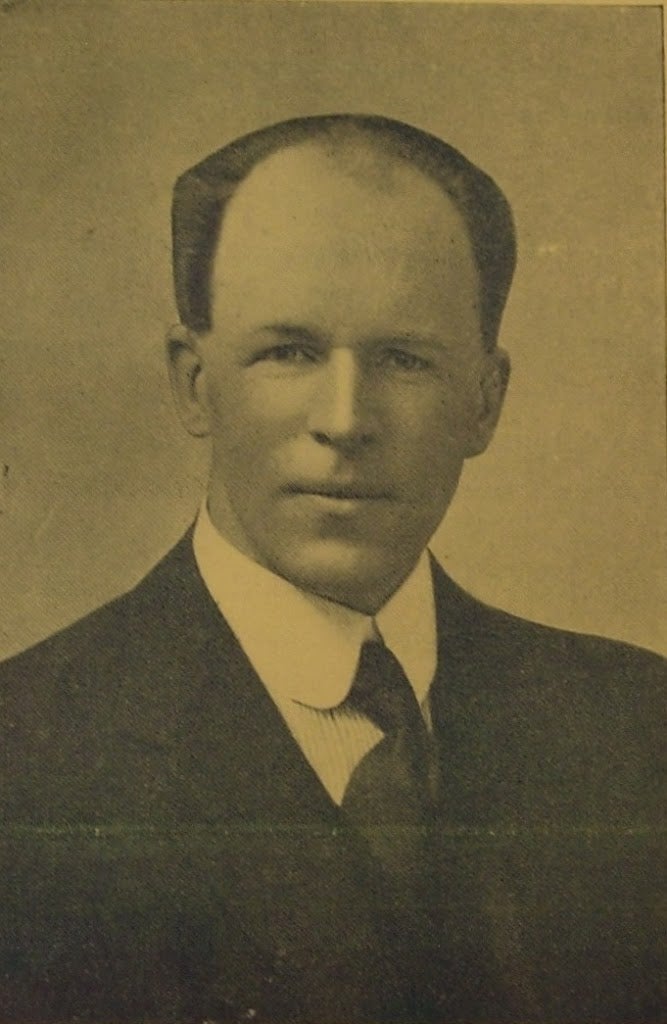

I know a bit about the Tory backbench group because its founding chairman, Sir Gervais Rentoul, was a distant relative of mine (second cousin twice removed)

As the name suggests, the 1922 Committee was founded in 1923. Its history is shrouded in myth. It is often believed, even by some of its members, that it was formed by Conservative backbenchers to overthrow the wartime coalition led by David Lloyd George.

That government was indeed brought down by a revolt of Tory MPs, but they met at the Carlton Club, and installed Bonar Law as leader of their party and prime minister. He immediately called a general election, which the Tories won in November. The following year, a group of new Tory MPs formed a dining club named after the year of their election.

The House of Commons is like a college, in that the members of each intake often feel a common interest. The 1922 Committee was unusual, however, in that it quickly became a pressure group for Tory backbench opinion, expanding its membership to include MPs elected in the 1923 and 1924 elections.

Soon it invited all backbench MPs to join and it tried to call itself the Conservative Private Members’ Committee, but the “1922” label stuck, helped by its association with the assertion of backbench power.

I know a bit about it because its founding chairman, Sir Gervais Rentoul, was a distant relative of mine (second cousin twice removed). He was MP for Lowestoft between 1922 and 1934, and thanks to him (and to Sir Graham Brady, the chairman since 2010) I was invited to the committee’s 90th anniversary party in 2013.

In fact, it was after Sir Gervais’s time that the committee became powerful, credited with the power to make or break party leaders. This was always slightly mythical, although plainly any prime minister needs to retain the confidence of the majority of the Commons, and, for a Tory leader, the committee was a useful channel of communication in maintaining that majority.

In Margaret Thatcher’s time the committee acquired a reputation as “the men in grey suits” who might arrive as a deputation to tell her her time was up. In the end, though, it was the straightforward device of a leadership election, which Thatcher failed to win outright on the first round, that deposed her.

Even so, David Cameron feared the power of the committee enough to try, as one of his first acts as prime minister, to bounce it into changing its rules to widen its membership to include government ministers. The committee, which is run by an 18-member elected executive, was having none of it.

So it is not surprising that journalists often attribute to the committee, or to its executive, the power to force Theresa May out of No 10. But this really only reflects the brute force of arithmetic. If a majority of Tory MPs – including ministers – want her out, she will have to go.

The reason she is still there is that a majority of Tory MPs are not ready yet to take the risk of having Boris Johnson as prime minister instead. The executive of the 1922 Committee voted last month by nine to seven, with two abstentions including the chairman, against rewriting the committee’s rules to allow a new challenge to May’s leadership.

The rules prevent a vote of no confidence in the leader within 12 months of the last one, in December. The decision to avoid a rule change was significant, but the rules cannot be changed in any case unless 157 Tory MPs vote to do so (50 per cent plus one of the total, 313). And then those 157 MPs would have to vote to remove May as their leader.

Despite the intimidating history of the 1922 Committee, I do not believe they are ready to do that yet.

Yours,

John Rentoul

Chief political commentator

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks