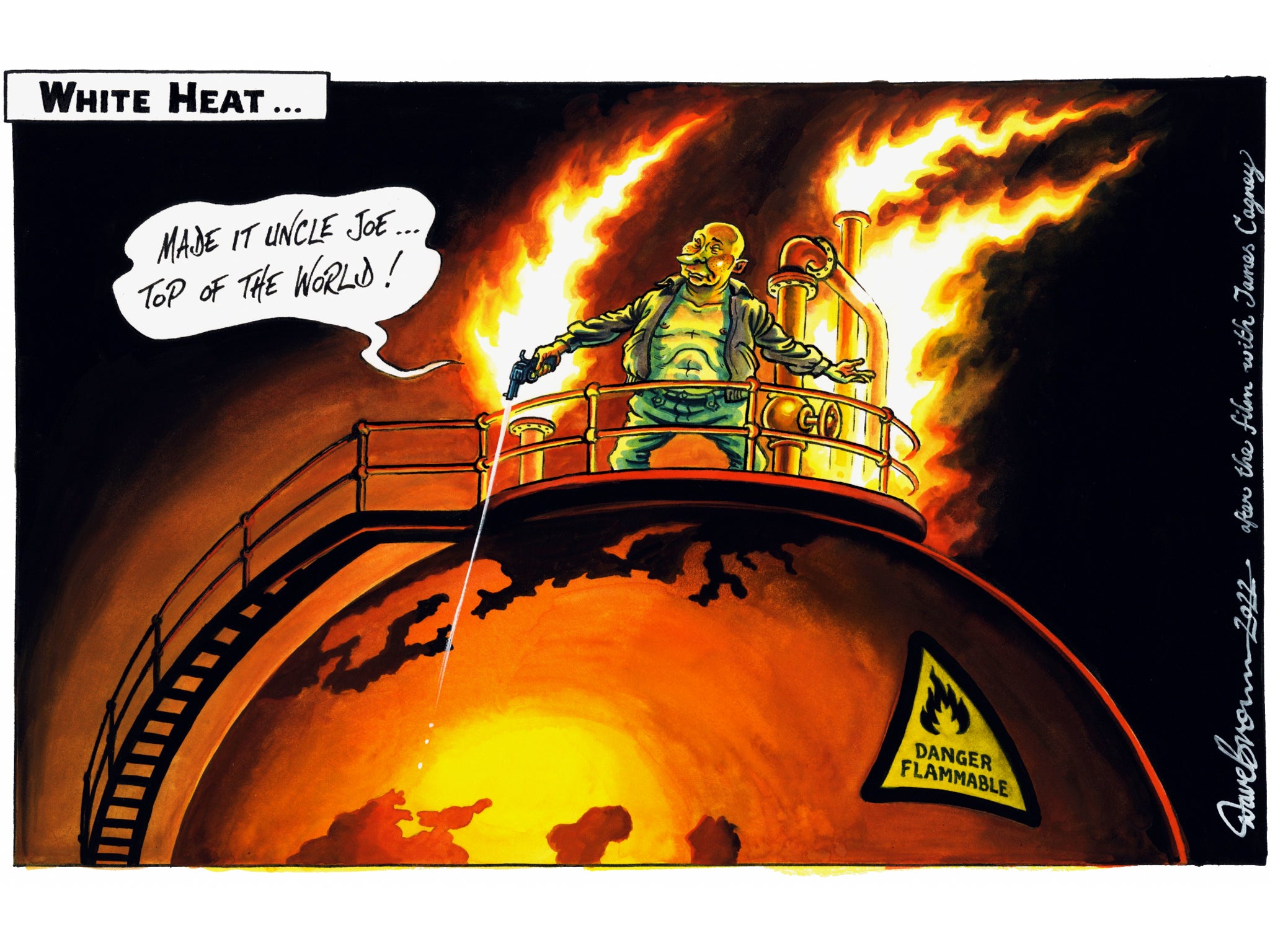

The war continues to rage. Russia has made it clear that it is not seeking an early diplomatic solution. Indeed quite the reverse. Sergei Lavrov, the foreign minister, has said it is “in essence” at war with Nato following deliveries of western weapons to Ukraine, which it views as legitimate targets. Nato, he says, is engaging in the conflict “through a proxy and is arming that proxy”.

Given Russia’s hardened line and Ukraine’s stout, heroic and effective defence, we must assume that this conflict will therefore continue for some time. This is a dreadful prospect and we can hope against hope this will not be the case.

But the western alliance must be prepared for the consequences of months of fighting and destruction. Those consequences are already being felt, with the burden of higher global food and energy prices falling on people, and nations, least able to cope. There are immediate effects, ranging from the rationing of cooking oil in British supermarkets to the soaring price of fertiliser worldwide. But these may be a foretaste of something much worse: a global famine.

The Biden administration is considering adding food aid for the poorest nations to the military aid package the president is preparing to send to Congress. The case for doing so is overwhelming on humanitarian grounds. The president of the Rockefeller Foundation, Rajiv Shah, said last week that there was a danger of a “massive, immediate food crisis” around the world. Oxfam has warned of a hunger crisis in east Africa affecting 28 million people. That is beyond question.

But there is also a powerful case for action on security grounds. The last surge in world food prices is widely accepted to have triggered the popular unrest that led to the so-called Arab spring, which in turn heralded a bout of disruption and conflict across the Middle East that continues to this day. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of wheat. Egypt is the world’s largest importer of wheat. Egypt is working towards self-sufficiency and seeking other sources, including India, but if Russian and Ukrainian supplies go down, then the price of the grain will go up.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

There is a further, perhaps even greater, concern. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fertilisers, the price of which has risen threefold in recent months. This will affect food prices everywhere. If price increases are a harbinger of actual fertiliser shortages, crop yields will inevitably decline. And it is farmers in the least-developed countries who will suffer most. That is how famines happen.

President Biden’s plan to add food aid to the future legislation is welcome in itself. It is even more welcome in that it will highlight the dangers ahead for the emerging nations. But of course it cannot be enough. America alone cannot solve the world’s looming food crisis.

All food producers, in effect the entire world, have to seek ways both of increasing their output and of stopping unnecessary waste. This is a challenge for all of us and we must rise to it. This will be a race against time. The possibility of a global famine in the 21st century is unbearable. The sooner we confront that prospect, the greater the chance we have to avert it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments