When it comes to voter ID, we should be removing barriers to participation in Britain’s democracy, not putting them up

The timing of the voter ID trial could hardly have been worse, coming so soon after the exposure of the Windrush scandal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Voter turnout in local government elections is rarely high. In council elections in England last year it was just over 35 per cent. This year’s figure is unlikely to be any better.

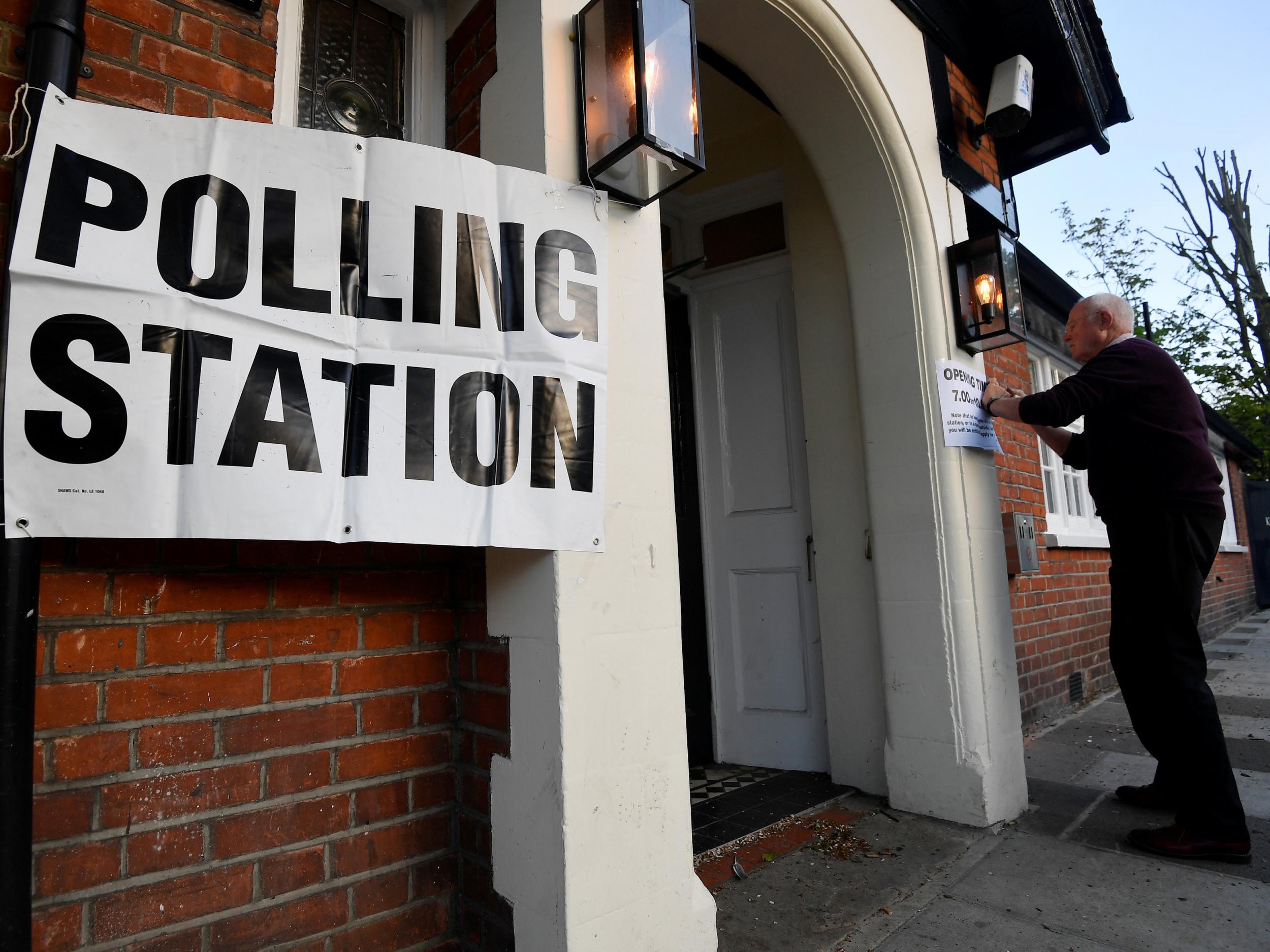

In this context, there will be considerable debate about the impact of the voter ID trial which has been conducted at polling stations in Woking, Gosport, Bromley, Watford and Swindon. In these places, at the recommendation of the Electoral Commission, voters were only able to cast their ballot if they produced valid proof of identity. Those who did not bring the relevant documentation were turned away; not all came back.

Critics have long expressed concern that forcing voters to prove their identity will disenfranchise sections of the electorate – especially vulnerable groups who do not have a stable residence or who lack the proof required.

Certainly the timing of the trial could hardly have been worse, coming so soon after the exposure of the Windrush scandal, which centred on individuals being forced to show documentary evidence of their citizenship status. The Labour Party made the point forcibly, describing the ID trial as “the same hostile environment all over again, shutting our fellow citizens out of public life”.

What’s more, questions remain as to the proportionality of identity checks given that the problem of electoral fraud in this country is relatively small – “tiny”, to borrow the Electoral Reform Society’s description.

Indeed, where evidence has emerged of electoral malpractice in recent times, it has tended to do so in relation either to campaign spending rules or to the misuse of postal votes. There is very little evidence to suggest that elections have been manipulated by individuals popping up at multiple polling stations, impersonating others in order to cast or control several votes.

When the Electoral Commission recommended ID checks in 2014, following its review of “electoral vulnerabilities” in the UK, it concluded that fraud had been attempted in no more than “a handful of wards in any particular local authority area” (notably of course in Tower Hamlets). Its proposal to require voters to prove their identity appeared to be premised on the potential risk of personation fraud, rather than overwhelming concern about the reality.

As the commission put it: polling station fraud “could become more vulnerable… as other processes (including electoral registration and postal or proxy voting) become more secure”. Yet that prophesy appears not to have been scrutinised: the trial is an attempt to deal with a problem that is not at the moment upon us.

Those who support the scheme point to the fact that ID checks in Northern Ireland have not generally presented difficulties for individuals wishing to exercise their democratic right. Voter turnout there has not, on the face of it, been affected since checks were first used in 1985 (or since legislation was passed in 2002 specifying which forms of ID could be used).

Yet in Northern Ireland, confidence in the integrity of the electoral process had been low. That is not true for the most part in the rest of the UK. Moreover, experience elsewhere – for instance in the United States – has given weight to the notion that making ID requirements more stringent has a disproportionate impact on potential voters from black and ethnic minority groups, and among the oldest and youngest portions of the electorate.

There is, it cannot be denied, a superficial attractiveness to the notion that you should prove who you are before you cast a vote. Protecting the integrity of the democratic process is vital to maintaining public confidence in governmental institutions; and for the overwhelmingly majority of people, taking proof of identity to a polling station is no more than an inconvenience.

Yet the fact remains that we should be removing barriers to participation in Britain’s democracy, not putting them up. As things stand, it seems likely that most people in this country are more likely to be worried by the low turnout at most elections than by the reality of personation fraud.

Full assessments of the trial which has been conducted at the present elections must be conducted in an open-minded way. But one thing should be clear: cracking nuts with sledgehammers can cause considerable collateral damage. Let’s not make democracy seem even more remote than to some it already does.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments