The case for the Covid vaccine passport trials outweighs the risks

Editorial: The arguments for mass vaccination remain overwhelming and, like secondary smoking, inhaling coronavirus is not something anyone should have to tolerate

It would be a tragedy of historic proportions if the great national effort to push Covid-19 back to the margins was now to be dissipated in misunderstandings. It would cost lives, many of them at a time when some countries on the continent are already facing a third wave of coronavirus infections, and epidemiologists cannot rule out such a repeat performance happening in Britain, even if the vaccine programme proceeds smoothly.

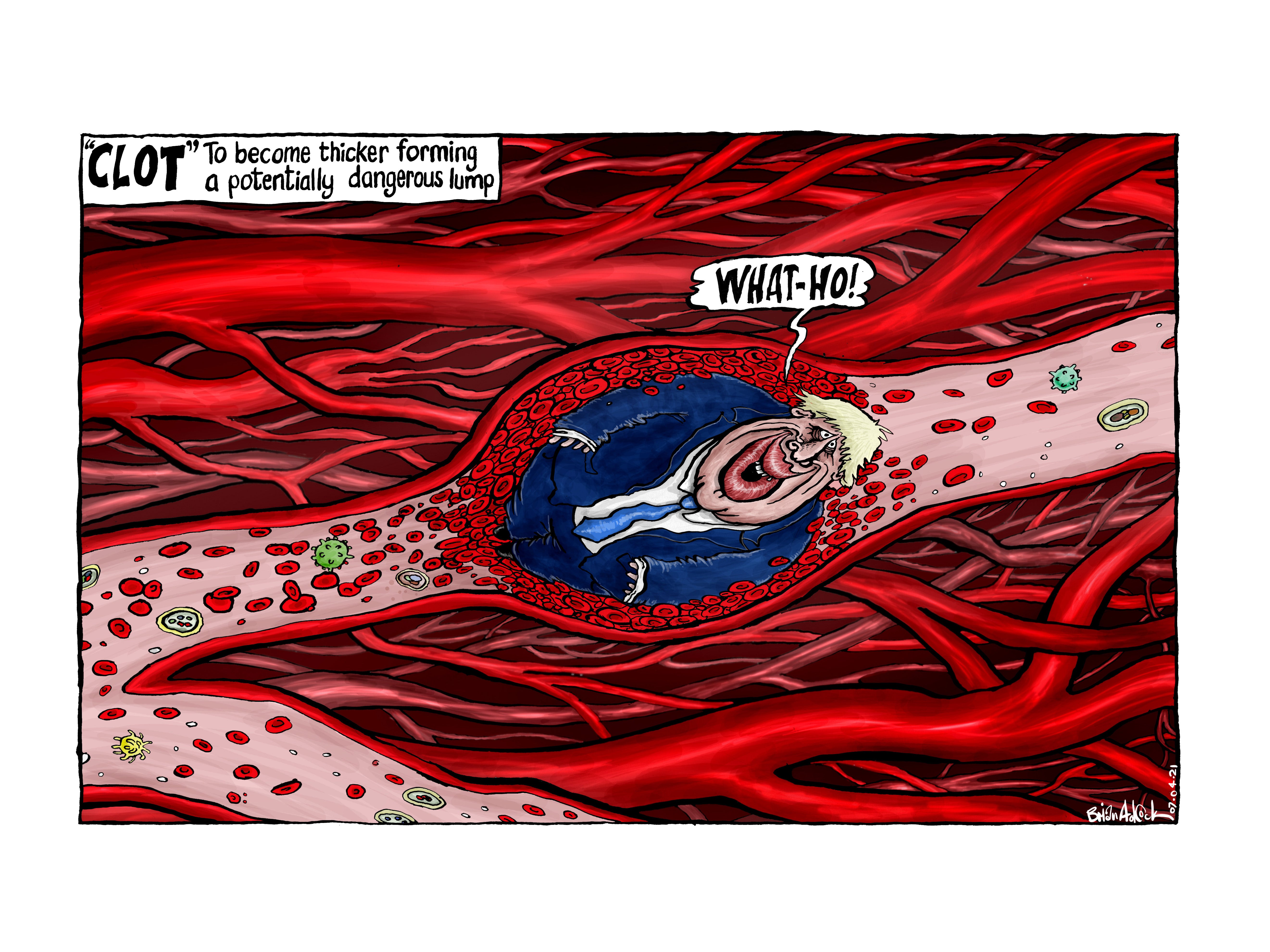

The most immediate issue is the decision by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to look into reports of a very rare blood clot possibly being associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine. For the moment, the guidance remains that the vaccine is safe, and people should continue to take it. Thus far, more than 31 million British people have received at least one dose, and there are no horror stories. The European authorities have already looked into the blood clots issue, and continued to recommend the widespread use of the AstraZeneca vaccine. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has said that the vaccine is safe and effective, but added that it could not definitively rule out a connection between the jab and the rare clotting events, and so was continuing to investigate. The EMA has denied suggestions it has found any causal link with the vaccine.

As ever in medicine, it is a matter of balancing risks. Given the choice between many more thousands dying from Covid-19 and having to investigate some possible side effects in a vanishingly small proportion of recipients, the arguments for mass vaccination as rapidly as possible remain overwhelming. That the authorities are taking the possible side effects seriously should demonstrate their own caution and conscientiousness about the programme – something that should provide reassurance, as should the experience of tens of millions of people in real-world usage who have suffered only trivial side effects.

It does not, at any rate, weaken the argument for proceeding with pilot schemes for coronavirus vaccine certificates, or so-called “vaccine passports”. None of these will be effective before June, if only because it will take that long to develop the software needed. Indeed, if past experience of test and trace is much of a guide, the electronic Covid-19 vaccine certificates will take many months to develop, and may possibly never work properly. If they do represent an assault on liberty, it is far from imminent.

The current political row about vaccine passports, in other words, is being conducted in something of a vacuum. That does not make it any less lively or important, though, or sometimes confused, as now. Government and opposition seem to shift their grounds of support or objection with every week that passes. Only a few weeks ago, the minister for vaccine deployment, Nadhim Zahawi, was adamantly opposed, citing their un-British quality: “One, vaccines are not mandated in this country – as Boris Johnson has quite rightly reminded parliament, that’s not how we do things in the UK; we do them by consent. We yet don’t know what the impact on transmission is and it would be discriminatory.”

Now Mr Zahawi has changed his mind and his tone, and refuses to rule anything out. Meanwhile, it is Labour that has gone cool on the idea, and is now stealing the Tories’ discarded clothes. Sir Keir Starmer, perhaps eyeing a tempting opportunity to inflict a humiliating defeat on the government, declared the vaccine passports “un-British”, as if he were some ally of Iain Duncan Smith, which, for these purposes, is where he may well end up. The shadow health secretary objects to the prospect of constituents in Leicester South having to show some Covid certification if they want to pop into the Highcross shopping complex for a fashion item from H&M or Next. Like Mr Zahawi once did, Mr Ashworth now sees them as “discriminatory”.

Read more:

While the government has at least come to a settled gradualist approach, ruling nothing out and proposing pilot schemes, Labour is all over the place, sometimes drawing back from the opposition in an unlikely alliance with Tory rebels, and sometimes sounding more open to the experiments. Despite vocal objections, the civil liberties arguments seem not to have convinced the bulk of the population and businesses. The looming problem as the great unlocking proceeds is that many patrons and customers will remain wary of going out, especially where there are safer online alternatives available.

Imposing strict social distancing on many venues, from pubs to sports stadiums, renders them uneconomic, even when they are free to open. Add in some consumer caution and a rip-roaring reopening seems less likely, beyond an initial excitement. The leisure economy, therefore, will take longer to open up, with businesses folding and people being made unemployed as a result. Far from deterring trade, a functioning Covid certification scheme, such as the one operating well in Israel, would encourage people to enjoy themselves in a close to Covid-free environment as possible. Market forces, if allowed to work their magic, might see some venues opt to introduce certification requirements (including for staff), with other venues offering more of a walk-in, no-questions-asked experience.

It is not so very different to the smoking ban in pubs and restaurants, which was introduced gradually across the UK by 2007, and has some of the same ethical arguments, such as balancing the health of the many against the rights of others. Like secondary smoking, inhaling coronavirus is not something anyone should have to tolerate, and people should not regard an evening in the boozer as some sort of universal human right, akin to free speech or the right to a fair trial.

No one will come up to anyone in the street in Britain and say, “Papers, please”. No one will make anyone carry their driving licence (though the police can now require its production within 14 days). Basic rights remain untouched. Just as you cannot go into a pub now and smoke tobacco, trade drugs, or drink under the prescribed age, so you will soon need to show that you do not represent a potentially lethal risk to the family at the table next to you. It does not seem such an outrageous “un-British” proposal. The pilots should go ahead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks