The crisis in Ukraine deserves the PM’s attention – but it will not save him

Editorial: The Ukraine crisis couldn’t be more real and the UK has an important role to play, both in deterring Russian aggression there and in bolstering the defence of Nato members

Boris Johnson is a man in whom the personal and the national interest always intermingle freely, but his visit to as yet unspecified destinations in eastern Europe cannot be entirely dismissed as a publicity stunt to distract from Partygate.

The Ukraine crisis couldn’t be more real and the UK has an important role to play, both in deterring Russian aggression there and in bolstering the defence of Nato members who may soon find themselves uncomfortably sharing a direct border with a Russian puppet regime in Ukraine – treaty allies such as Estonia, Poland and Hungary. Like most places east of the old Iron Curtain, they still have a vivid memory of life under Russian domination.

If the prime minister’s visits to the region help to reassure them of British resolve and assistance, then that is all to the good. The provision of defensive weapons to Ukraine and Nato allies, along with the deployment of troops in Estonia, seems entirely appropriate; such measures would not be under consideration were it not for past and present Russian aggression, including cyberattacks.

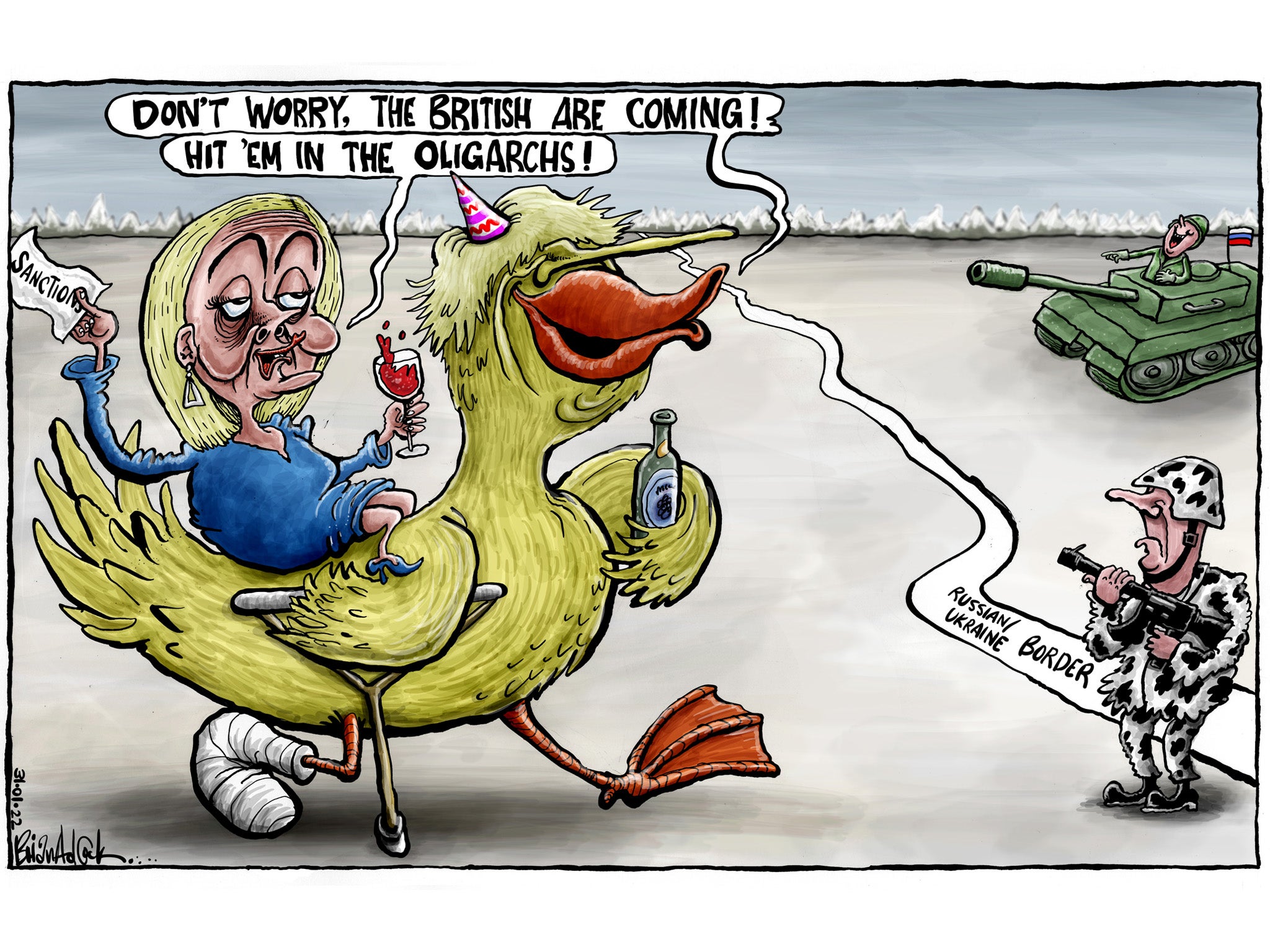

The foreign secretary, Liz Truss, will visit Ukraine this week, and next week she will travel to Moscow – providing that peace, of a sort, holds. Perhaps she will convince her counterpart that a Russian war in free Ukraine would turn into an exhausting and bloody quagmire, as did past campaigns in Chechnya, Afghanistan and, much further back, Finland. On the other hand, the Russians might decide that they know their own history well enough without Ms Truss’s tutorials.

At a time when the west is weakened and divided, and Putin’s Russia is assertive and revanchist, such visits should be a source of strength rather than a means of appeasement. At least, in this sphere of policy, the government is behaving responsibly and putting the national interest first. If Russia feels able to pressure and blackmail key EU partners and Nato allies, then Britain’s own national interest is vitally affected. If Germany, the continent’s largest economy, suffers an acute energy crisis because supplies of gas from Russia cease abruptly, then that is Britain’s problem too. Brexit hasn’t abolished economic geography and blessed Britain with splendid isolation.

Of course, the British contribution to defence – and to economic sanctions – would be even more effective from inside the EU, using its influence to steer Europe to a more united and muscular response, but Brexit has cordoned off that option. It is, to say the least, interesting that Russia tended to favour Brexit; a united Europe standing in collective security against Russia was a nightmare for the Kremlin.

The prime minister likes to claim that he is leading Europe’s efforts to restrain Russia. It sounds fanciful – as if President Macron would be attracted to the idea – but even if he is manning the phones as a kind of informal coordinator-in-chief, he has not had much visible success. France is still pursuing its own initiatives, while Germany has turned pacifist.

Fortunately, despite some lapses and gaffes, the Biden administration is at least committed to Nato in a way that Donald Trump was volubly not. While the suspicion was always that President Trump wouldn’t go to war with Russia over tiny Estonia, or even Poland, it’s a little more likely that Mr Biden would. Indeed, if Mr Trump were still in power, he might today be visiting Mr Putin and his puppet counterpart in Kiev to sign a US-Russia treaty of friendship – a de facto recognition of the new Russian empire. That, at least, has been avoided.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The UK also has a unique position in this crisis, as London is a favoured spot for allies of the Russian leader to park themselves and their money. If economic sanctions have any hope of succeeding – and they did not in respect of the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of eastern Ukraine – then they have to be targeted at the court of Vladimir Putin.

The government is right to bring forward fresh legislation to shut down the “London laundromat”, to apply sanctions to a wider range of Russian entities, and to discuss the idea, first raised by America, of slapping personal economic and travel sanctions on Mr Putin himself as well as his inner circle. The government has, in any case, long been too slow to “lift the veil” on Kremlin interests in the UK, to the annoyance of our allies.

In due course, Mr Johnson will have to account for breaking his own lockdown laws, misleading parliament, and partying while the rest of the nation stuck to the rules and made its sacrifices in lonely grief for loved ones. Despite his efforts, he won’t escape justice, whether or not there’s a crisis in Ukraine – or indeed a fresh Covid wave in the UK.

Events, real or confected, will not save him, even if they rightly command the attention of the public. Mr Johnson is the wrong man to lead Britain through any crisis but for now, he should be supported by the opposition in one that has yet to reach its violent crescendo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks