Whether or not it was Dominic Cummings who leaked Boris Johnson’s text exchanges, as the prime minister apparently believes, the leaks have performed a public service. They have drawn attention to the dangers of what Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, calls “government by WhatsApp”.

The public response by Mr Cummings to being accused of the leaks is unedifying for Mr Johnson, although not unexpected. “It is sad to see the PM and his office fall so far below the standards of competence and integrity the country deserves,” Mr Cummings wrote in a post on his blog – the type of criticism the prime minister no doubt became used to receiving over his handling of the Covid-19 crisis – but he will not appreciate the boost this story has been given.

If the aim of the anonymous briefing against Mr Cummings was to take the heat out of the story involving the text exchanges with Sir James Dyson, that has failed spectacularly. Mr Cummings own accusations about the circumstances surrounding the Covid-19 lockdown leak and the refurbishment of Mr Johnson’s Downing Street flat will no doubt lead to some difficult questions.

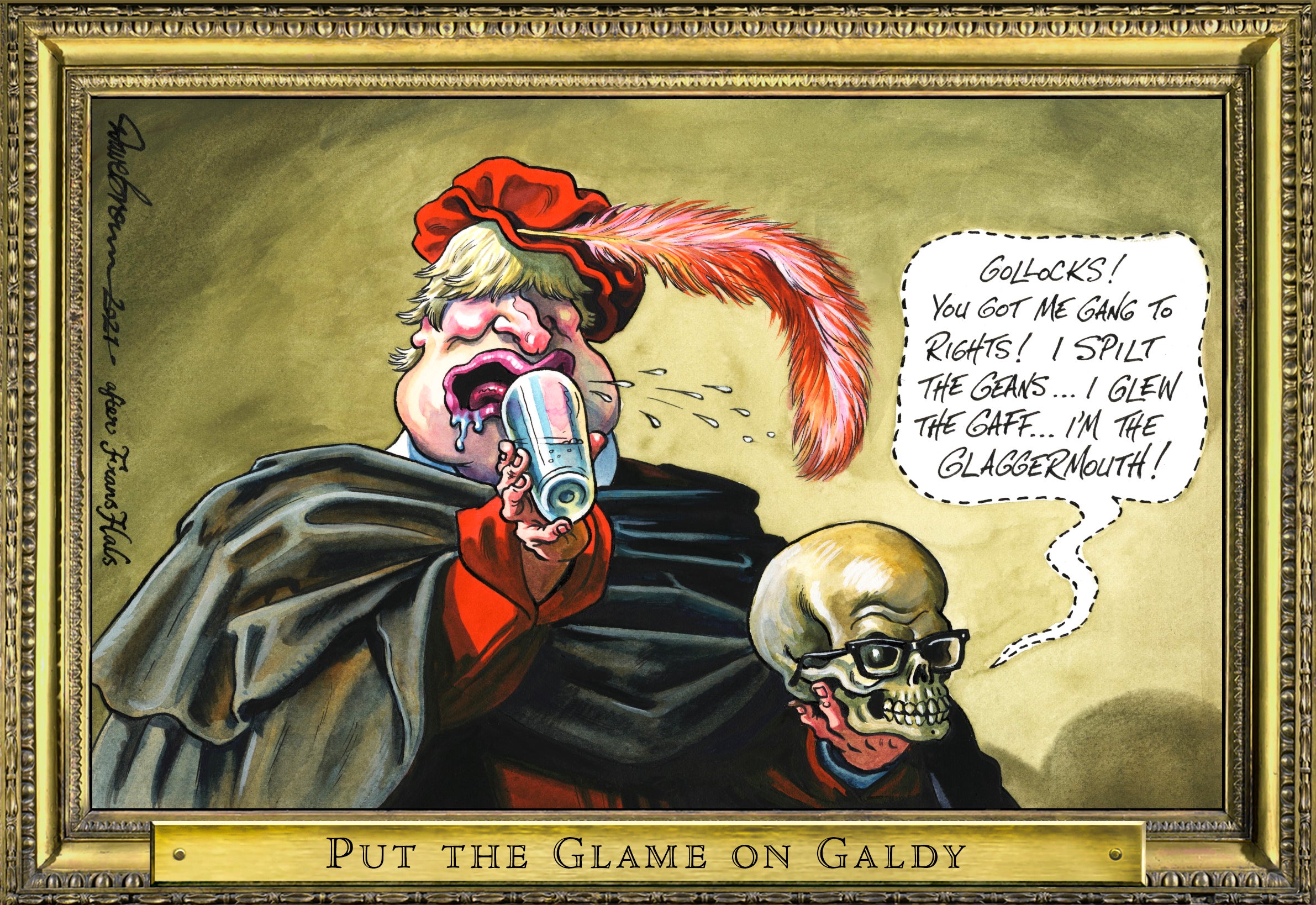

The whole episode is a reminder that communications – both within government and the presentation of information to the public – has been a constant thorn in the side of Mr Johnson and his team, mostly one of Downing Street’s own making. Mr Johnson isn’t the only prime minister to have had to deal with issues over communication – but he certainly has a very singular way of going about it.

Long ago, when a Labour government was bringing in a freedom of information law – something for which Tony Blair admonished himself later as a “nincompoop” – Jack Straw, the home secretary, warned that government communications would be done by Post-it Notes in order to avoid disclosure.

In fact, his fears were largely unfounded and most government business has continued to be properly recorded so that, through freedom of information requests if necessary, ministers can be held to account for their decisions. There has always been an unregulated sphere of private conversation, in which ministers discuss matters, including with lobbyists. Not all their conversations have a civil service note taker present, and not all their phone calls have a civil servant listening in.

The question of record-keeping has become more complicated, however, with the use of mobile phones. Mr Blair was the last prime minister not to have a personal mobile. Gordon Brown caused consternation in the civil service with his use of his phone and personal emails; David Cameron was better organised, and it was in his time that it was clearly established that government business was subject to freedom of information law even if – as in the case of Michael Gove and Mr Cummings, who was then a special adviser at the Department for Education – it was conducted via personal email accounts.

Yet it would seem that the rules have not fully caught up with the ways in which ministers, including the prime minister, use their personal phones. In Mr Johnson’s case, he still uses the same phone number as when he was a journalist. It is therefore widely known, and he is wide open to being lobbied without any form of accountability.

Of course, in the case of Sir James’s texts to Mr Johnson asking for assurances about the tax treatment of his staff being sent to the UK to work on producing ventilators, they were fed into the civil service machine, so that an answer from the Treasury could be given. They became part of the official record. That is, presumably, how they have found their way into the public domain.

Mr Johnson says, with his characteristic vivid expression, that “you’re out of your mind” if you think Sir James’s texts were “dodgy”. But that is not the point. The purpose of civil service record-keeping is to be able to verify that nothing “dodgy” has taken place. If the prime minister had been lobbied by someone with a less straightforward request than Sir James, and had not forwarded the texts to officials but merely sought to obtain an advantage for someone, then we, the voters, would be none the wiser.

The main lesson of recent leaks, including the details of Mr Cameron’s exchanges with the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, and other officials on behalf of Greensill Capital, has been that the rules governing lobbying by former ministers and prime ministers need to be tightened up. But an important secondary lesson is that a prime minister should not keep their personal mobile phone from their old days.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments