The UK’s defence structure needs updating to meet modern challenges

History is full of nations that made the error of fighting the last war, or the one before that, rather than the one looming ahead

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Should the opposition parties be making political capital about the cyber hack of the NHS? The answer to that is undoubtedly yes, if their attacks – admittedly opportunist and only to be expected in the middle of a general election campaign – actually yield some answers and some understanding about what has gone wrong. That is the point of democratic accountability. The answers we have received so far have been unsatisfactory, and it is little wonder that the NHS has suddenly shot up the chart of voter concerns.

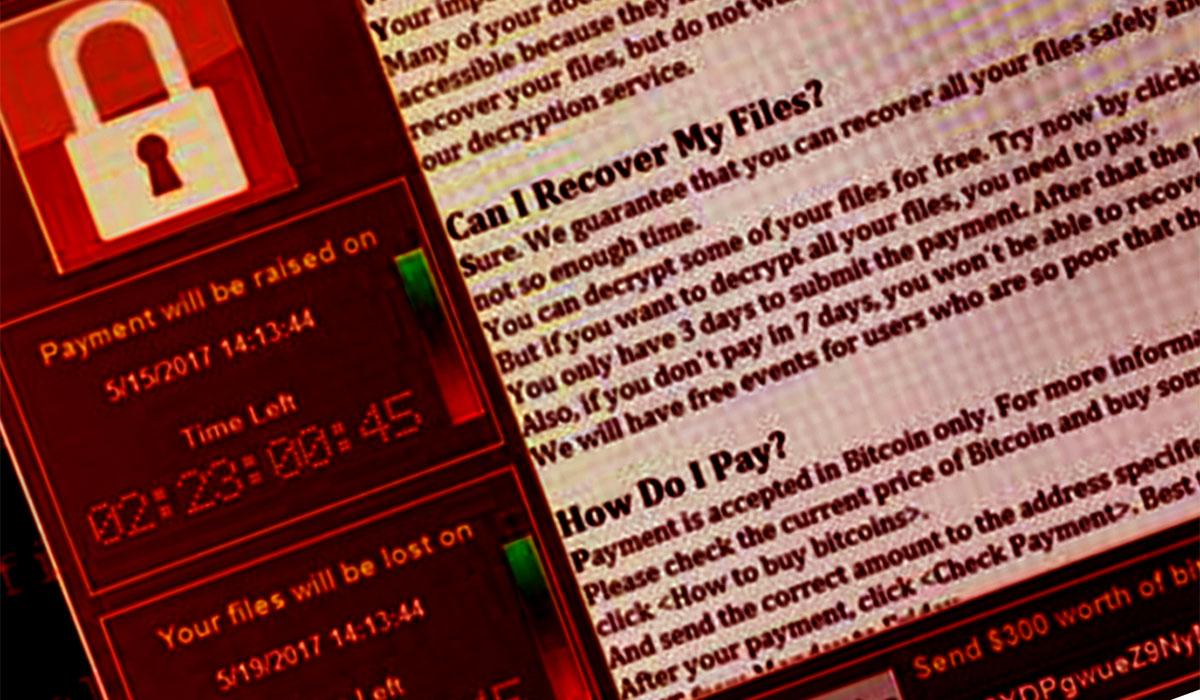

What went wrong is that some health authorities did not spend a relatively trivial sum of money on protecting their outdated IT systems. Fragile as they were, Microsoft were offering a “patch” that would remove some of the more obvious vulnerabilities some months ago. That the money was not spent is the central question. Was it because of a failure of central government to fund such expenditure, indeed to withdraw funding for it? Was it the incompetence of the trust authorities in not taking action swiftly enough? Or some combination of the two?

This is what is not clear and, when the new Parliament meets at Westminster, it will need to find out as a matter of urgent priority. That is a matter for Jeremy Hunt at the Department of Health as much as for Amber Rudd at the Home Office; it is not purely a question of criminality, but also of our own contributory negligence.

We can assume that a thorough review is taking place of all our security systems. The Defence Secretary, Sir Michael Fallon, has sought to reassure us that the nuclear deterrent and other defence systems are proofed against interference, and yet we also know that the hacker will always get through. It is in the nature of this crime, no different to the bank robbers or highwaymen of the past, that it is a game where the authorities and the criminals are in a constant race to outflank each other, and an unending race at that. We should place these latest attacks – and they are only the latest and most disruptive of a trend that has been rising for many years – in that context.

Yet, from what we know of what happened with the NHS Microsoft systems, we also know that it was far from inevitable that the hackers should have succeeded this time round. That stands even though many other private and public sector systems around the world were affected. If this successful ransomware assault on the NHS proves anything, it is that our defence structure – in the widest sense of the word – needs to be focused and revised to meet some very modern challenges.

We still seem to be stuck in a Cold War mentality where, as ministers keep telling us, the nuclear deterrent has protected us for more than half a century. Indeed it has – but mostly against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Dangerous as Russia may be once again, we need also to think about the threats that are demonstrably upon us today.

Should we not devote ever more resources to terrorism in all its asymmetric and “domestic” forms, where a car or a knife or a single smuggled firearm is all that is needed to inflict casualties and cause chaos and fear. Should we not – as Jeremy Corbyn has suggested – consider where the next global conflicts are going to arise as the effects of climate change and water shortages make themselves known? Should we not also renew our defences in outposts such as the Falklands? And should we also not do far more than we evidently have to maintain the resilience of our IT systems, public and private, against malicious attack, either from criminals, terrorists or unfriendly foreign governments? Who can say, for example, that our general election is or will be free from hacking or disruption, when the evidence that that happened in the US and France appears so strong? British nuclear weaponry was no use to us in countless modern conflicts, from Northern Ireland to the South Atlantic to Kosovo to Sierra Leone through to Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya.

In the end, setting the priorities for defence spending, whatever its level, is about the correct analysis of the risks. The Russians are certainly one such, but if we devote too many of our scarce defence resources to that admittedly real threat, then in a finite world, we necessarily neglect making sure that patients’ records, the banking system or the way we elect a government are free from attack. It is rather as if Sir Michael and his colleagues are still telling the generals to plan for Napoleon’s next move, or what Rommel might next have planned. History is full of nations that made the error of fighting the last war, or the one before that, rather than the one looming ahead. The NHS cyber attack seems another rather embarrassing example.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments