Switzerland rejected universal basic income - but that doesn't mark the end of the idea for Europe

For too long, 24-hour commitment to raising a child or keeping an elderly relative alive – a job that is as unrelenting and difficult as it is rewarding – has been dismissed as “not really work” because of a lack of financial recognition

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

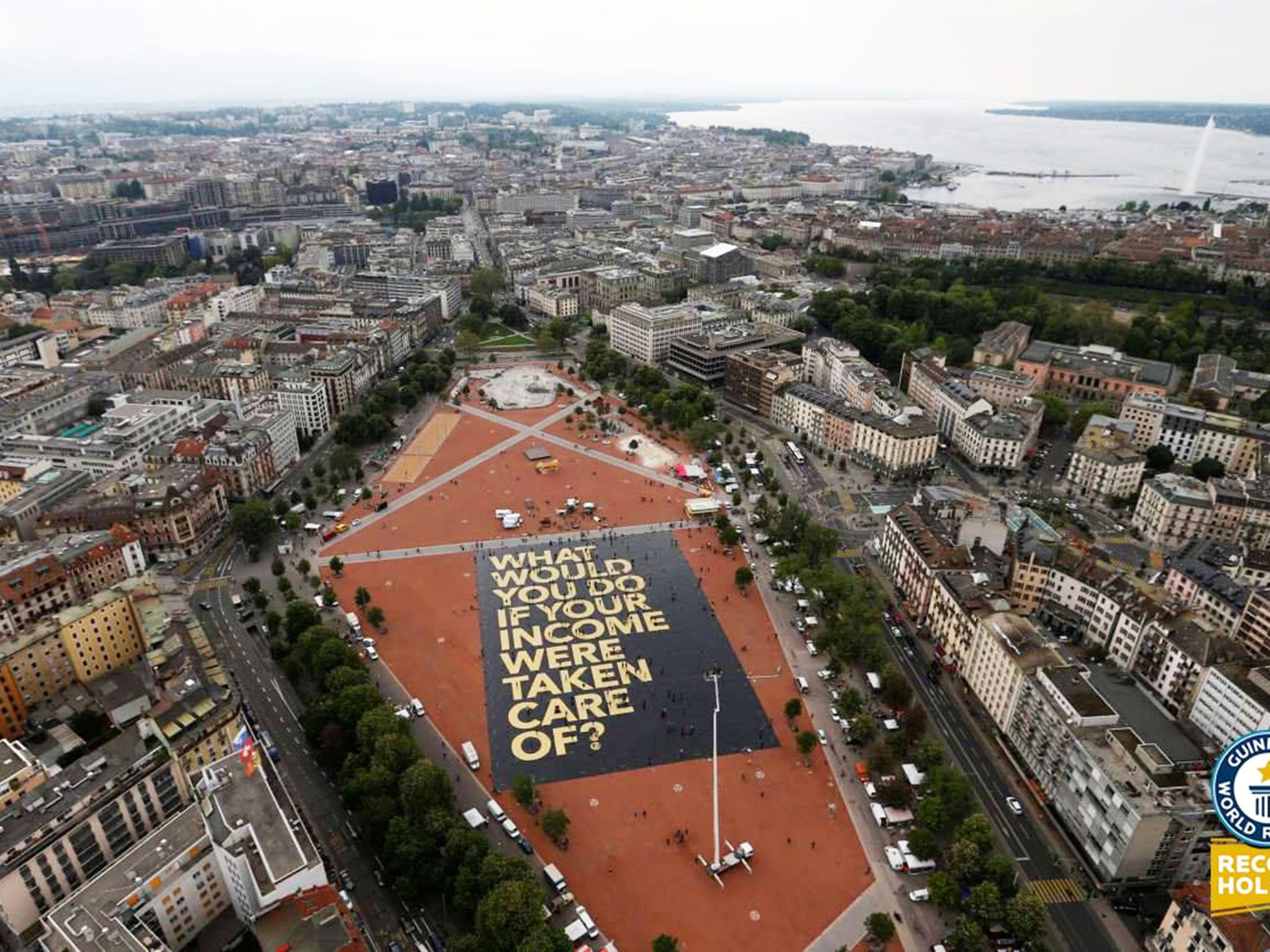

Your support makes all the difference.Switzerland rejected a plan to introduce a basic income this weekend, in a move that surprised few but disappointed many. More than 100,000 people, after all, had signed a petition demanding a referendum on the controversial economic idea, which calls for adults to be paid an unconditional monthly income, whether they work or not.

Advocates of the universal basic income argued that as much as 50 per cent of the work done in Switzerland – and, indeed, globally – is unpaid, such as care work, child-rearing and community projects, despite being absolutely vital for society. Many hoped that the introduction of a flat state benefit would encourage more creativity and philanthropy, as well as change social perceptions of caring for older people or children. For too long, pro-basic income campaigners argued, 24-hour commitment to raising a child or keeping an elderly relative alive – a job that is as unrelenting and difficult as it is rewarding – has been dismissed as “not really work” because of a lack of financial recognition. Those behind the campaign suggested a monthly income of 2,500SFr (£1,755) for adults and 625SFr per child would be appropriate, based on the cost of living in the country.

It is true that we often dismiss and devalue work done outside traditional work environments, even as that work takes a very real toll on the people who do it. We’ve seen this “emotional labour” feature in feminist debate in particular, as statistics are released time and time again that show women are doing a disproportionately high amount of work in the home (taking responsibility for school runs, housework, looking after ageing parents and organising holidays, for instance) even when their working hours are the same as those of their male partners. A universal basic income could help to challenge perceptions of emotional labour, and to reframe it as “real work”, hopefully resulting in increased gender equality.

Nevertheless, it was clear that Switzerland would not vote to reform its welfare system so radically. Few politicians spoke out in favour of it before the vote, and many commentators dismissed it as a flash-in-the-pan moment of socialist campaigning fervour afterwards. Politicians were also quick to point out that a universal basic income in one country with relatively high levels of immigration would open Switzerland up to welfare tourism, and therefore would never become a realistic prospect.

However, it could pay, literally, not to be so hasty. With the Canadian province of Ontario reportedly planning to trial the system soon, as well as Finland and the Dutch city of Utrecht, it’s clear that European and North American populations – and their governments – are taking the prospect seriously. There is serious political ambition to shake up our financial systems and our working environments – unsurprising, really, when we consider how massively those environments have changed in the past 20 years with myriad technological innovations and their effects. This was clearly not Switzerland’s time, but international trends suggest it would be naïve to conclude that it will never be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments